A quick note that this piece covers the topic of suicide.

A minor, but not insignificant, commentary on 2020 that I heard more than a few times last year: How significant that Beethoven’s 250th anniversary would, due to COVID-19, be dominated by the silence of concert halls. The implication here, of course, is that Beethoven’s deafness would have meant that the silence of the concert halls, emptied and closed, would have been analogous to his experience of a full concert hall, mid-symphony.

The comparison is reductive, and likely inaccurate based on medical and musical scholarship in the intervening years. But the intention behind it carries an explanation, if not an excuse: Humans have always been prone to make sense out of the seemingly senseless. “In some ways suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning,” Viktor Frankl writes in Man's Search for Meaning (1946). But how is that meaning found? What happens if it isn’t found? And where does making sense of the past leave us in the present?

Two physical ailments and their psychological ramifications, affecting two creatively-radical, yet psychically-fragile men, open and close this story.

Ludwig van Beethoven was probably somewhere between 26 and 28, in the waning years of the 18th Century, when he first experienced symptoms of hearing loss. American writer and actor Spalding Gray was 48 or 49, in the final decade of the 20th Century, when he first experienced symptoms of what would be later diagnosed as a macular pucker.

Both men came of age in revolutionary eras, reconciled the personal with the political in their art, and left bodies of work that remain difficult to separate from some of the ways that their own bodies betrayed them. Both men sought to find meaning in their ailments, questioning causes and pursuing treatments.

But Beethoven’s and Gray’s stories don’t neatly overlap as history repeating. Gray’s eyesight was eventually resolved, while Beethoven’s hearing continued to deteriorate through the course of his life. But anniversaries are often occasions for reevaluations — reevaluations of work, but also reevaluations of the stories told about those works. What we do with those reevaluations makes us active participants in the myth-making.

By his late 20s, Beethoven had abandoned his German hometown of Bonn (along with its memories of his dead mother and alcoholic father) and made his home in Vienna. In the Austrian capital, he had quickly established himself as a piano virtuoso. According to biographer Jan Swafford, 1798 Beethoven wasn’t the scowling caricature that has lived on in souvenir shops. Rather, in that time, he “appeared chipper and optimistic.” True, he had suffered from a bout of typhus the year before, but now he was among the inner circle of Vienna’s musical elite. He enjoyed the attention and patronage of some of the city’s wealthiest families. He was also coming into his own as a composer, and had spent part of this period studying with Antonio Salieri.

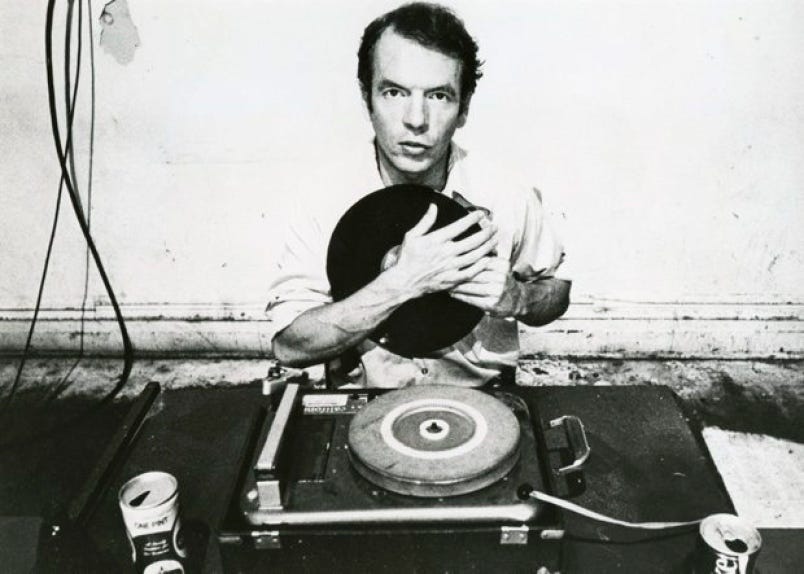

Two centuries later, in 1990, Spalding Gray was in his late 40s and on a similar professional precipice. An actor by training, he had begun writing, developing some of his earliest pieces following his mother’s suicide when Gray was 26, and spending much of the ’60s and ’70s with the Performance Group (now known as the Wooster Group). A break came in 1984 when Gray was cast in a small role as part of Roland Joffé’s The Killing Fields. The following year, he premiered Swimming to Cambodia, an evening-length monologue that he wrote and performed (from the stark setting of a wooden desk), detailing his time working on the film. Things came full circle when Jonathan Demme adapted Swimming to Cambodia for film in 1987 (with a score by Laurie Anderson). As Gray entered the last decade of the 20th Century, he had published six books and, post-Killing Fields, 9 additional film credits to his name.

Through his studies with Salieri, Beethoven had started and abandoned several operas, including one that he had worked on in the first few years of the 1800s. The work itself isn’t notable, except for the fact that, years later, Beethoven would cite it as the source of his hearing loss. Speaking with pianist Charles Neate in 1815, Beethoven explained that he had been working with an ill-tempered tenor at the time. The tenor had already rejected two settings for an aria that Beethoven had written. Meeting at the composer’s apartment for a third try, the tenor seemed satisfied and left, promising to work with the music.

Relieved, Beethoven turned to some other work that he had backburnered in order to meet the singer’s unreasonable demands. But, just half an hour later, he heard a knock at the door: The tenor was back for another rewrite. Beethoven then told Neate:

“I sprang up from my table under such an excitement of rage that, as the man entered the room, I threw myself upon the floor as they do upon the stage, coming down upon my hands. When I arose I found myself deaf and have been so ever since. The physicians say the nerve is injured.”

Neate recounted this meeting to Alexander Wheelock Thayer for Thayer’s massive, multi-volume Beethoven biography (published between 1866 and 1887). Even then, however, Thayer wasn’t quite sure what to do with this origin story, describing it as “extraordinary and inexplicable.” Medical experts, though unable to conclusively determine the causes of Beethoven’s deafness, have never clung too hard to this myth, either. Instead, they’ve turned to the less dramatic, more plausible explanations including syphilis, the typhus that Beethoven had suffered in 1797, vascular insufficiency, or — perhaps most plausible — cochlear otosclerosis.

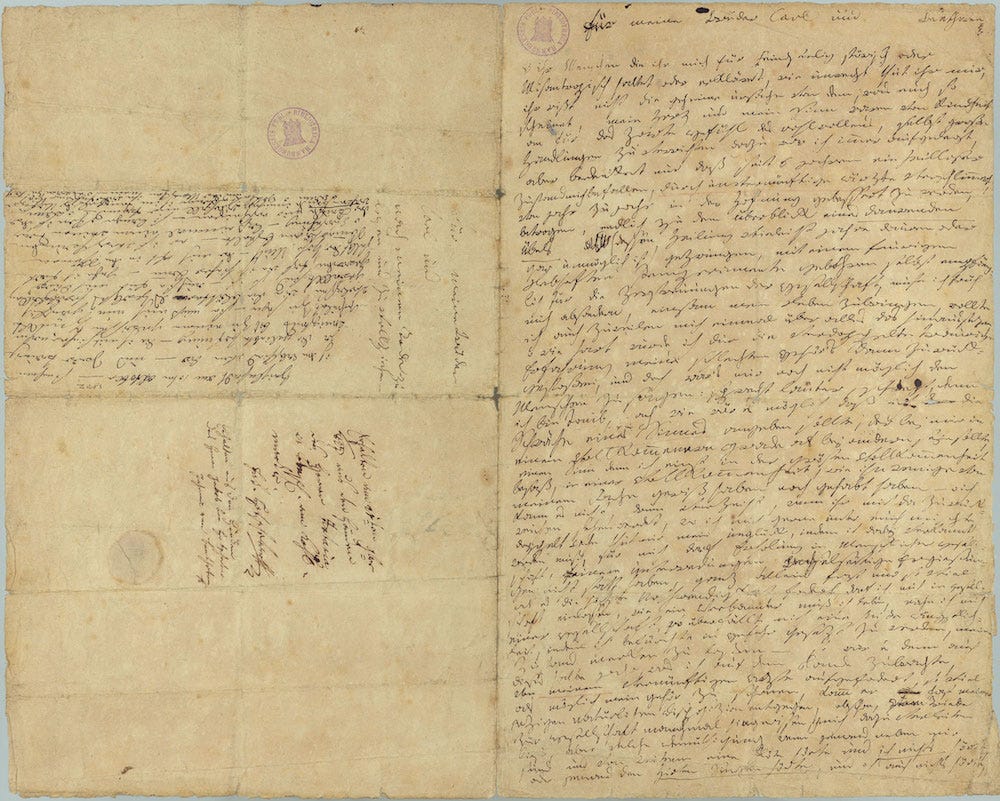

It’s likely that Beethoven himself didn’t always cling to this event as the root cause of his deafness. In one letter to his friend, physician Franz Gerhard Wegeler, dated June 29, 1801, the composer makes what is likely the first mention of his gradually-weakening sense of hearing. Then, he described it as a condition that had persisted in fits and starts over the last three years:

“The trouble is supposed to have been caused by the condition of my abdomen which, as you know, was wretched even before I left Bonn, but has become worse in Vienna where I have been constantly afflicted with diarrhea and have been suffering in consequence from an extraordinary debility.”

Regardless of the cause, Beethoven sought out most every treatment he could. Dr. Johann Peter Frank prescribed a litany of tonics, including almond oil (which didn’t help). Another doctor, whom Beethoven only refers to as “a medical asinus” suggested cold baths. The “more sensible” Dr. Gerhard von Vering, medical advisor to Emperor Joseph II, prescribed tepid baths in the Danube.

“My ears continue to hum and buzz day and night. I must confess that I lead a miserable life,” Beethoven added to Wegeler. “For almost two years I have ceased to attend any social functions, just because I find it impossible to say to people: I am deaf. If I had any other profession I might be able to cope with my infirmity; but in my profession it is a terrible handicap.”

Out of concern for his livelihood and reputation, Beethoven was incredibly guarded with his advancing hearing loss. In some way, the other aspects of his personality helped: Known to friends and colleagues as absentminded, Beethoven could write off his hearing loss as forgetfulness. Internally, he began to distance himself more from his social life, which seemed to carry the greater psychological difficulties. While silence served Beethoven well in some ways — the silence of the country versus the city fed him spiritually, and he was most likely sensitive to loud noises and shouting even before his hearing loss owing to what Maynard Solomon describes as “the traumatic events within his family constellation” — it was also incredibly lonely and isolating.

“Plutarch has shown me the path of resignation,” he wrote to Wegeler, adding that he would continue to try the treatments recommended to him “though I feel that as long as I live there will be moments when I shall be God's most unhappy creature.”

If Beethoven took the stoic’s view of his deafness, Spalding Gray treated his temporary visual impairment with far more rage and resistance. He was also not shy about disclosing it and making it part of his canon with the 1994 monologue Gray’s Anatomy.

But this, too, carried ramifications. As Gray’s star steadily rose in the 1980s, recognition came at a cost. Nell Casey, editor of The Journals of Spalding Gray, describes this period and its discontent:

“Gray promised his life to his audiences.… [and] as his career gained traction in the eighties, this worry developed into a darker and more fixed sense of destiny, one that left Gray feeling trapped and afraid. This anxiety — that he had gambled his privacy for fame — would haunt him for the rest of his life.”

His fears of illness, death, and destiny coalesced with his own post-script of an origin story for his temporary loss of vision. While facilitating a storytelling workshop in upstate New York in 1990, Gray joined 15 students for a simple centering exercise.

Sitting in a circle, each person was to look into another person’s eyes. No talking. When they grew tired of looking into one person’s eyes, they could move on to another. Gray locked eyes with Azaria Thornbird, whom he described as “the Immaculate Conception”: blonde hair, blue eyes, dressed in white. Staring at Azaria’s face long enough, Gray imagined it becoming a ball of pulsing white light

“It was burning my retinas and dilating my pupils. I couldn't take my eyes off it,” Gray says in his 1994 monologue, Gray’s Anatomy (which begins with this story). “But all of a sudden the ball of white light came into a point and went Pffff! Whoom! and vanished out the window behind her head, and her face recomposed and smiled back at me.”

Gray’s Anatomy catalogues the myriad ways that Gray seeks treatment for what was in fact a macular pucker, the cause of which was unknown. While his ophthalmologist recommended a minor surgery, many of the treatments he seeks are an effort to bypass the procedure. He quits drinking. He eats a diet of raw vegetables. He returns to his mother’s practice of Christian Science (which eschews medical care). He goes into a Native American sweat lodge.

For all the medical advances between Beethoven’s ear and bowel issues to Gray’s comparatively simple macular pucker, the list of treatments seems all the more baroque in Gray’s Anatomy. This culminates with Gray traveling to the Philippines to be treated by a man he calls in performance “Pini Lopa” — the Elvis Presley of psychic surgeons. When Gray consults with Pini Lopa, the surgeon explains his technique of reaching into the body with only his hands, removing offending pathological matter. When Pini Lopa tells Gray of pulling an eye out of a patient’s skull, washing it off, and returning it to the socket, Gray asks how he reconnected the veins.

“We don’t know,” Pini Lopa responds. “This is a mystery.”

Somewhere, you have to imagine, Beethoven would have called them both asses.

In reality, Gray was less hell-bent on the idea of Pini Lopa (who, in Gray’s journals, is called Alex and seems to be more of a traditional spiritual healer than a gold-lamé GP) as the solution to his problems. He also seemed less hell-bent on finding a solution to this particular problem, perhaps due to his ambivalence towards surgery.

“I tend to adjust to what happens to me, ADJUST to events rather than attack and try to fix them,” he writes in his journals in July of 1990, echoing Beethoven’s evocation of Plutarch.

“THE OPERATION feels like an attack on my eye. THE OPERATION FEELS like a major attack. But I had to follow out this PSYCHIC SURGEON IDEA because of how much it has appeared in my life. Do I dare ask the question: WHO AM I MAKING THIS DRAMA FOR?”

To Spalding Gray, his life and the stories that composed it was the raw material he used for his art, for his work. In an interview for Gray’s Anatomy, he would later tell the New York Times: “I would not have done those things if I was not trying to make a redeemable story around the eye issue.”

Yet, while art balances fantasy with reality, as Maynard Solomon writes in his 1984 collection Beethoven Essays, “one usually cannot distinguish between the real and the imagined, between direct representation and sublimated transformation.”

The relationship between what we see and what we make of it is never fully resolved. Tied up with Beethoven’s initial stages of hearing loss is his 1805 “Eroica” Symphony. The work begins with its own version of a Pffff! and a Whoom!: a pair of identical, emphatic chords that arrive and depart in fast succession.

“It is a revolutionary moment, musically speaking,” writes Laura Tunbridge in her (excellent) new biography, Beethoven: A Life in Nine Pieces. “Yet the revolution of this symphony is, for now, quiet and gone within less than a minute. Greater upset is still to come.”

While Beethoven wrote only one opera, the “Eroica” is as much an opera as it is a symphony, charting a hero’s journey from the first two notes to the funeral march, ending on a note of transfiguration in the final movement, which serves as a sonic avatar of sorts for the Enlightenment. Poet and “Ode to Joy” author Friedrich Schiller described it as “the assertion of one's own freedom and regard for the freedom of others.”

Dated October 6, 1802, the Heiligenstadt Testament shows Beethoven in a more desperate, despondent state than he was a year earlier when writing Wegeler. His deafness can no longer be written off as absent-mindedness. He has instead, in the public eye, morphed into “malevolent, stubborn, or misanthropic.”

“How greatly you do wrong me,” Beethoven added of this misconception. “You do not know the secret causes of my seeming so.… Oh, how harshly was I repulsed by the doubly-sad experience of my bad hearing, and yet it was impossible for me to say to men, ‘Speak louder, shout, for I am deaf.’ How could I possibly admit such an infirmity in the one sense which should have been more perfect in me than in others, a sense which I once possessed in highest perfection, a perfection such as few surely in my profession enjoy or have enjoyed?”

Through a certain lens, the Heiligenstadt Testament can read like a suicide letter (even making explicit reference to the idea). Had Beethoven intended to take his life after writing this note to his brothers? This, as Pini Lopa would say, is a mystery. One other way of interpreting the Heiligenstadt Testament, however, is as a prototype of the “Eroica.” Maynard Solomon describes the text as “a leave-taking — which is to say, a fresh start. Beethoven had metaphorically enacted his own death in order that he might live again. He recreated himself in a new guise, self-sufficient and heroic.”

Solomon was neither the first nor the last to posit this theory. In his 2011 study on disability in music, Extraordinary Measures, Joseph N. Strauss writes that the Third Symphony’s “narrative of disability overcome… forms part of the history of disability, and that history in turn provides an essential context for the interpretation of Beethoven's life and work.”

But, as the Heiligenstadt Testament shows, Beethoven’s was not necessarily a linear narrative of heroic overcoming that happened once and whose end-results were permanent and unfluctuating. Nor is the narrative that Beethoven “triumphed” over his deafness (in any sense of the word) still valid in 2021. Questioning the centuries-old Disability model, which would consider deaf communities as built around a shared deficit versus a shared culture, musicologist Devin Burke challenged the qualitative nature of the facts surrounding Beethoven’s hearing loss, “as both a private experience and a socially-conferred identity.”

Not that Burke is suggesting that we throw out the Beethoven story with the bathwater, or even that the mythology is categorically negative. But, isolated from the other elements of Beethoven’s biography, it loses some meaning. Even as he gained fame as a composer, Beethoven would spend his life contending with the psychological ramifications of his deafness, but also face the same reckoning with traumas caused by family dynamics, Napoleon’s invasion of Austria, and the authoritarian rule of Metternich in Vienna.

Biographers have pointed to the general disarray in which Beethoven lived, his tendency to move apartments on a dime (his addresses in Vienna numbered at least 39, if not more), and his loneliness (“To live alone is like poison for you in your deaf condition,” Beethoven reminded himself in 1817 in his Tagebuch) as all symptoms of some chronic form of depression. Dr. Aloys Weissenbach, a surgeon from Salzburg who once met Beethoven, observed: “His nervous system is irritable in the highest degree and even unhealthy. How it has often pained me to observe that in this organism the harmony of the mind was so easily put out of tune.”

“Notwithstanding my healthy appearance,” Beethoven himself wrote to Archduke Rudolph in 1816, “I have all this time been really ill and suffering from a nervous breakdown.”

If, with the “Eroica,” Beethoven fashioned himself into a hero — even just for one day — Spalding Gray doesn’t exactly do the same with Gray’s Anatomy, or any of his other monologues. “I’m not an artist,” he once wrote in his journals. “I'm a public neurotic.” Ultimately, the sight in his left eye returned following the minor, ophthalmologist-recommended macular scraping. But Gray would also slide in and out of depression, culminating with a traumatic injury that fractured his right eye socket in 2001, and Gray’s suicide in 2004.

For his 60th birthday in the summer of 2001, Gray traveled with his family to the Irish countryside. Driving down a country road one night, Gray’s wife, Kathie, at the wheel and Gray himself in the backseat with a friend, the party collided head-on with a van. Both Gray and Kathie were knocked unconscious; because Gray wasn’t wearing his seatbelt, he was also thrown forward. The front of his skull collided with the back of his wife’s.

In a local hospital, doctors diagnosed a broken hip that would receive follow-up treatment in Dublin. But what the doctors in Ireland had missed was a compound fracture that eclipsed Gray’s skull and the socket of his right eye. The injury was caught and treated in New York, and for a time Gray seemed to be in high spirits — albeit lingering pain. After the summer, however, Gray and his family had made good on their plans to move from a beloved homestead in Sag Harbor to a larger house in North Haven. (The actual move was postponed by one day, having initially been scheduled for September 11, 2001.)

Immediately, Gray sensed it was a mistake, and the repetition of one that his mother had made, moving houses in Rhode Island 34 years earlier and lapsing into a breakdown from which she wouldn’t recover. “I am far gone,” Gray wrote in his journals on September 18, 2001. “The loss of the house and the neighborhood of houses is too much for me. I dull myself with champagne and beer and wake up in pure panic.”

He began to construct a narrative around this event, as Nell Casey wrote in the editorial notes for his Journals.

“Moving to the new house was a fatal mistake. His own mother had made the same mistake when she moved away from her home in Barrington, Rhode Island… to a secluded property in East Greenwich, Rhode Island. Now he, too, had left behind a beloved house to live farther from town, where Gray also felt isolated and uneasy. This story became his obsession, a mythic rant. He told it again and again as he tried to explain why he could not bring himself out of his black mood.”

Neurologist Oliver Sacks, whom Gray consulted, echoed Casey’s idea of a constructed narrative. He recalled Gray wondering whether he was manufacturing crises for material for future work.

Still, nearly two years after the accident and the house, Gray hadn’t fully recovered. Previous depressions, and even previous breakdowns, had seemed to be somewhat porous, flexible, less solid, as Sacks would later write. This episode “had unprecedented depth and tenacity.” He attempted suicide in 2002. He left notes that his family discovered, before he was found again. He spent four months in an in-patient psychiatric clinic, where he received more than 20 treatments of electroconvulsive therapy. These treatments only seemed to further isolate and bury Gray pre-accident. Neuropsychiatric tests at UCLA in 2003 showed additional damage and deterioration in Gray’s brain, owing to the scarring from the impact of the crash. When doctors told him he may never again be able to write and perform, Gray was, in Kathie’s words, “morally devastated.”

Gray left his last note in January of 2004. His body was discovered when it washed up on the Brooklyn waterfront two months later. “He had always wanted his suicide to be high drama,” wrote Sacks, “but in the end he said nothing to anyone; he simply disappeared from sight and silently returned to the sea, his mother.” For a man who crafted his own mythos as he lived it, Gray’s death seemed both real and imagined.

Even that, however, seems to overly-romanticize a death that could have been prevented. This week marked the 17th anniversary of Gray’s death, and the intervening years have been nearly two decades of rapid reassessment of how we treat and talk about mental illnesses, and the meanings we affix to suicide (and what separates meaning from fact).

“We now read these works with a greater awareness of the different perspectives that can inform our interpretations, and how those perspectives do not represent ‘natural’ truths but are generated in specific historical moments,” Burke writes of Beethoven, reexamining the line between direct representation and sublimated transformation.

A few weeks ago, composer Gabriela Lena Frank (who was born with high-moderate/near-profound hearing loss) did just that in a piece she wrote for the New York Times, “I Think Beethoven Encoded His Deafness in His Music.” One byproduct of Beethoven’s hearing loss was an elongated piano keyboard, allowing for greater resonance and vibration, and expanding on the number of octaves — a turning point in getting us to the 88 keys we know today. “Is it an exaggeration,” Frank wonders, “to say that composers after Beethoven, the vast majority of them hearing, were forever changed by a deaf aesthetic?”

In this way, I wonder if and how the Beethoven model of mythologizing will map onto Gray. (This is perhaps an interest that is as personal for me as Beethoven is for Frank; both as someone who lost her own father to suicide and who navigates the world with my own episodes of depression.) In some ways, Gray doesn’t need any more mythos than that which he built for himself. But then, the same could be said for Beethoven after the “Eroica.”

There, we’re left with a similar inch or so between art and reality. But all of the meaning, we believe, lies in that inch.

Thanks for subscribing to Undone. See you in two weeks.