It’s 1943, and Hamburg has just been firebombed by Allied forces during World War II. Roaming the aftermath, writer Hans Erich Nossack wonders, “Was all this just scenery for a fantastic opera?” Two years later and about 200 miles further east, Europe marked VE day with the unconditional surrender of Germany to Allied forces on May 8, 1945. The Soviet Army had reached Berlin the month before, and by the time of the ceasefire, the landscape was its own, perhaps even more extreme version of Nossack’s Hamburg.

The opera metaphor was apt, both for Germany’s present and its future. As the inheritors of a musical legacy that spanned from Glinka to Stravinsky, Stalin’s Army understood what could be gained from culture in a crisis: Music signaled normalcy. It was as much a stabilizing factor for the German people as it was for the Russians, who, as harpsichordist-turned-politician Hans Pischner said, “knew exactly how important it was to reestablish the cultural life” of the city they had just conquered.

Concerts came together informally, with Red Army soldiers singing “Heidenröslein” in German to beleaguered civilians who crowded in whatever space was available, or outside among the rubble of a failed empire. In the documentary Classical Music and Cold War, you can see footage of one concert in the shell of what was once the Schauspielhaus Berlin (now the Konzerthaus). Just two weeks after Germany’s unconditional surrender, the Berlin Philharmonic played its first post-war concert. When US soldiers arrived in the capital a few months later, they walked into a city whose cultural life had been completely organized by occupying Russians.

The question then became: How to rebuild Berlin’s operatic culture? Before the War, the city had no fewer than four major opera houses, all of which were now destroyed. As Abby Anderton notes in Rubble Music, in April of 1945, composer Richard Strauss proposed that each city should build two opera houses: one for smaller works, including Mozart and operetta, and a larger hall for bigger works (e.g., his own). In a similar vein, Albert Kehm of the Staatsoper Stuttgart suggested that the transition be gradual, as Anderton puts it: “companies should begin with Gluck and Mozart, or even French and Italian Spieloper, absolutely avoiding monolithic works by composers such as Wagner.”

As Berlin became divided by the four powers (with American, Soviet, British, and French sectors), an artistic arms race began between West and East. The Russian sector seemed to be considering Strauss’s suggestion, reopening both the Staatsoper Unter den Linden and the Komische Oper, which originally adhered to its name by focusing on comic works to help restore civilian morale.

Women in Berlin watch a concert among the ruins of the city, ca. 1945. (Screenshot from Classical Music and Cold War, Arthaus, 2012)

All of this continued at pace, with the Staatsoper in the Soviet sector and the Städtische Oper in the British Sector reopening in exile, both with works that spoke to resurrection and liberation (the Staatsoper performed Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice, the Städtische Oper opted for Beethoven’s Fidelio). In 1955, the Staatsoper returned to its restored home on Unter den Linden reopened, and plans were in place to reopen the opera house in Charlottenburg in 1961 with Don Giovanni, sung in German. While the Staatsoper stuck to its original architecture (whose plans had survived the war), however, the Städtische Oper (which would rechristen itself the Deutsche Oper Berlin) went for a modern, mid-century look that obliterated the memory, and all of the baggage that came with it, of the pre-war house.

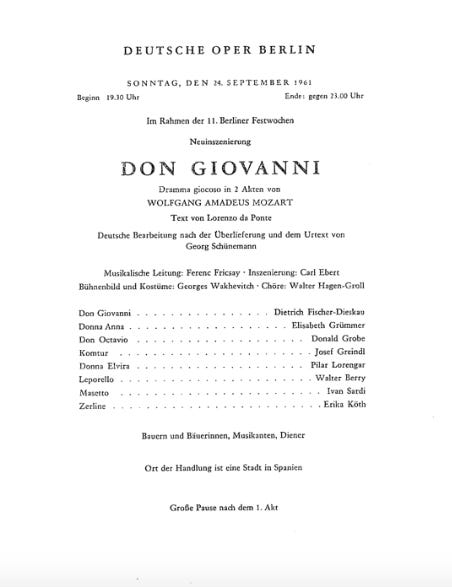

Soprano Christa Ludwig, on the other hand, called it “a box on the inside and on the outside… cool, functional, matter-of-fact, and without charm.” She had a preview of the house before it reopened when her then-husband, Austrian bass-baritone Walter Berry, was contracted to sing Leporello in Don Giovanni, alongside a starry international cast that also included Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in the title role, Elisabeth Grümmer as Donna Anna, Pilar Lorengar as Donna Elvira, and American tenor Donald Grobe as Don Ottavio. Hungarian-born conductor Ferenc Fricsay was to conduct, and the production was helmed by Max Reinhardt protegé Carl Ebert (who had been born in Berlin to a Polish father and an Irish-American mother).

Original program from the Deutsche Oper Berlin’s reopening in 1961 (courtesy of the Deutsche Oper Berlin)

Cool, functional, and matter-of-fact as the new opera house was, architect Fritz Bornemann’s design represented a fresh start, one without the lingering ghosts of Berlin’s recent past. A total of 88 slabs of washed-out concrete created a protective barrier against the six lanes of traffic on Bismarckstrasse, while also allowing for the front of the building to be a full floor-to-ceiling window, letting in light and creating a sense of openness.

The concrete slabs that formed the Deutsche Oper and their use as a barrier would take on new meaning a few weeks before Don Giovanni opened when the Berlin Wall went up on August 13, 1961.

To say the Berlin Wall “went up” on August 13 is a bit of a misnomer. Orchestrated as a covert operation by the Soviet-satellite German Democratic Republic on the night of Saturday, August 12, it would have been impossible to build an entire wall overnight. The problem was that, with an average of 1 in 4 East Germans fleeing the GDR between 1945 and the beginning of August, 1961, the government couldn’t afford to announce their plans to close off the border, effectively keeping their citizens sequestered from the West, in advance without risking an influx of refugees.

An October, 1962 New Yorker article by John Bainbridge noted that, because of the ongoing flow of East German refugees to West Germany (many through the divided city of Berlin), “East Germany earned the distinction of being the only country in Europe, if not in the world, that had both an excess of births over deaths and a steadily declining population.” East German leader Walter Ulbricht was most concerned about the economic losses that came from this, particularly from the country’s younger workforce, which cost roughly $1.5 billion (in 1960 dollars) to train, and which was rapidly evaporating. Earlier on in the summer of 1961, he told London’s Evening Standard:

“This is no political emigration but filthy man-trade, which is carried out with large sums of money invested by Bonn authorities, West Germany monopoly capital, and the United States spy centers in West Berlin.”

(Bainbridge notes that “filthy” was a favorite word of Ulbricht’s to describe the West; he and his colleagues had also called this exodus “filthy head-hunting” and “filthy slave trading.”)

The lasting impact of “Barbed Wire Sunday” would be the 28-year reign of the Berlin Wall. Overnight, families were divided — many not reuniting until the end of the 1980s, houses overlooking the border zone were boarded up, and Berliners who were content to live in one sector and commute to work in the other were suddenly out of a job. The physical manifestation of the Wall (which was really two walls separated by a 160-yard “death strip”) went beyond geography and created a sense of isolation for Germans living on both sides of the divide.

In spite of my best efforts, I’m unable to tell how this abrupt shutdown of Berlin’s borders affected the workforce for the Deutsche Oper Berlin’s Don Giovanni. All of the principal performers seemed to either live in the West, or were visiting from abroad. The Deutsche Oper Berlin’s archives also lacks any information pointing to chorus or orchestra members, stagehands, dressers, makeup artists, or administrative staff.

But even if everyone working for the company, from the executive staff to the stagehands, were living in the West, they were still affected. (One could even say that West Berliners faced the greater impact of the Wall as it was less of a Wall surrounding the GDR as it was surrounding West Berlin, an island otherwise surrounded by East German territory.)

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (L) and Ferenc Fricsay (R) rehearse Don Giovanni at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, 1961

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau himself had narrowly missed being caught on the wrong side of the Wall. Years later, he would still remember sitting in the Admiralspalast theater declining an offer from Staatsoper leader Ernst Legal. All he would say later of the meeting was that he “tried to make him understand that [I] had more to gain from accepting the offer from the Städtische Oper than [I] did from the invitation to start in the studio of the Staatsoper.” For him, the “sinister Wall,” erected “over the belated protests of the vacillating Western powers” put an end to what he called the “display window” that was West Berlin.

Likewise, as much as Christa Ludwig hated the new Deutsche Oper, she had more hatred for “that ugly monster [that] stood in the middle of the city.” Beyond the aesthetics, Ludwig (who was a Berliner) and Berry were afraid to come to the city, reasoning, because they were uncertain of what was going on with the Wall. For all they knew, the Russians would completely take over the West’s display window.

It’s possible, too, that the stress of mounting this new Giovanni outweighed, or at least displaced, the stress of the new political climate. “The way rehearsals were structured was anything but helpful,” Fischer-Dieskau recalled in his 1989 memoir, Reverberations. There were struggles with Ebert, who seemed “entirely concerned with the musical arrangement.” Fricsay, who was already in the advanced stages of a cancer that would take his life in 1963, clashed with Ebert’s ideas on the work in a way that Fischer-Dieskau and his fellow castmates couldn’t reconcile. That the premiere was going to be recorded for television also introduced new challenges, like fencing instructions for Fischer-Dieskau and Josef Greindl (who was singing the Commendatore) to make their duel more believable in close-up.

“Whatever we might have achieved in rehearsal up to that point was lost under the sergeant-like barks of the trainer,” recalled Fischer-Dieskau, who was having flashbacks to his military service and time in a POW camp. “Terrible visions arose of a new barracks discipline. A rebellious word of protest had no effect whatever and so we crept away, soaked with sweat and scorned, like poor sinners.” Ebert retired as the Deutsche Oper’s general manager the day after Don Giovanni opened on September 24, 1961.

The subsequent recording of Don Giovanni (which was released on DVD in 2011) seems to reveal the stiff nature of the rehearsal process and irreconcilable differences in the visions between Ebert and Fricsay. Perhaps some of that stiffness also came from the uncertainty of the brave new world that an entire city, if not a continent, had been unwittingly thrown into less than six weeks earlier. What purpose did music serve in this moment?

Like the cast, the New York Times’s music critic Harold C. Schonberg, visiting Berlin for this occasion, seemed to both enjoy the diversion, while also sensing that the performance counted as a cultural (and therefore political) win for the West, with high praise for Fischer-Dieskau and the cast.

“With the closing of the border, the situation in the East Berlin houses is precarious, while the new one in the opposing sector opened with a burst of glory,” he wrote in the opening of his review, while adding at the end that the champagne reception for the entire audience was “a pleasant end to the evening, and a few moments more of forgetfulness about the cement walls and barbed wire a short walking distance away.”

In 2020, a year where we’re living in a new pattern of isolation, we’re also coming to terms with how difficult it is to “read” art of the past through the lens (and social norms) of the present. Hindsight is a great editor for history, and it’s easy for us now to see the Wall, which had already been fully built by the time many of us were born — and, for some of us, even totally down before we were born, with the perspective of knowing what happened in November of 1989.

“When the Berlin Wall was taken down in 1989, I sang in Berlin and felt very happy, as if I was joined with all those who still remembered Berlin when it was one,” Ludwig recalled in her 1994 memoir, In My Own Life. “But how disappointed I was that many young people were completely indifferent to the reunion. Of course, they had never experienced an undivided Berlin, and I thought it was horrible that almost two generations knew only a divided city.”

But can art fully exist out of the context of history and politics? Watching the Deutsche Oper Berlin’s 1961 Don Giovanni now while trying to block out its surrounding political context and take the performance simply on its own terms, would be to ignore some of the terms that contextualized its performance and creation. Terms that also dovetailed with the political era in which Mozart and librettist Lorenzo da Ponte wrote the work. Ebert’s issues with the libretto included that it “never really gives the hero a chance to be a conqueror, while presenting him only dimly as a lover.” To him, Don Giovanni was in a border zone between incorrigible comic hero and a sinister villain who, in his first scene, has just raped a woman and then murders her father.

Don Giovanni, 1961 at the Deutsche Oper Berlin (courtesy of the Deutsche Oper Berlin)

Fischer-Dieskau himself seems to live within this anxious in-between of Giovanni’s character, more sad than suave, more volatile than refined. When he sings (in German translation) the line “Viva la libertà,” or “Long live freedom,” shortly before the end of Act I, you can’t help but think of the freedom that was at stake for Germans in the audience and in the six lanes of traffic just on the other side of the Deutsche Oper’s 88 concrete slabs. In an August 13 op-ed for the New York Times, Pulitzer-winning journalist Arthur Krock noted that, between East and West diplomats, “it has been demonstrated that a word which means one thing to Moscow has an entirely different meaning in the allied capitals, regardless of the fidelity and skill of the translators.” In elaborating on some of these words over the following paragraphs, Krock pauses to note that the final word in his partial list merited its own paragraph:

“Freedom.”

The Enlightenment era in which Mozart originally wrote Don Giovanni was a similar age of anxiety: Liberty and freedom were among the ideals of Enlightenment thinkers, but this would also come at the cost of major political transitions (transitions that included the French Revolution and Reign of Terror). While philosophers argued for the triumph of reason over fear, this was nevertheless a terrifying prospect for individuals of all classes.

Don Giovanni may be the one who calls for a long life to liberty, but this is only in service of his role as a libertine. He’s also a symbol of the old guard, who rests on his station in order to avoid all reason or responsibility, instead spending his time traveling around Europe and sleeping with as many women as he can. (“Only as sensuous beings are we dependent, as rational beings we are free,” wrote Enlightenment-era philosopher and poet Friedrich Schiller.) Giovanni’s death at the end of the opera is the collateral damage of progress. It was a collateral damage that many Berliners knew too well.

Thanks for subscribing to Undone. Next week’s story will visit Berlin on the other side of the Berlin Wall with Leonard Bernstein’s 1989 performance of Beethoven’s 9th.

Further Reading and Watching

I originally wrote about the 1961 Don Giovanni and its connection to the Berlin Wall when this DVD first came out in 2011 for WQXR.

Rubble Music: Occupying the Ruins of Postwar Berlin, 1945–1950by Abby Anderton (2019) provided the Hans Erich Nossack reference, as well as Richard Strauss’s and Albert Kehms’s recommendations for post-war opera in Germany

The Seduction of Culture in German History by Wolf Lepenies (2009)

In My Own Lifeby Christa Ludwig (1994)

Reverberationsby Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (1989) may be one of the most beautiful memoirs I’ve read, by a singer or otherwise

“Die Mauer: The early days of the Berlin Wall” by John Bainbridge for The New Yorker (October 20, 1962)

“A Question of Definition: Different meanings that East, West put on different words is a major factor” by Arthur Krock for The New York Times (August 13, 1961)

“Opera: New House of Song in Berlin” by Harold C. Schoenberg for The New York Times (September 24, 1961)

Overture 1912: Die Deutsche Oper Berlin(Arthaus, 2013)

Classical Music and Cold War: Musicians in the GDRby Arthaus (2012) is a fantastic documentary that I also owe a lot to in terms of research

The entire 1961 Don Giovanni is on YouTube, separated into Act I and Act II