To talk about Ari Aster’s Midsommar — most notably its final scene — is to talk about Maria Callas.

In Aster’s 2019 folk-horror film, set in a woodsy Swedish commune of Hårga, only one of the four visiting Americans is left standing. Having been crowned May Queen as part of the Hårga’s annual midsummer festival, Dani (Florence Pugh) is now laden with flowers — her head emerging from a cape of them that makes her look like an herbaceous volcano.

She is, likewise, burdened with a major decision: Every 90 years, the Hårga complete a ritual sacrifice of nine lives. They have eight already — including two of Dani’s compatriots — and now she needs to select the final body for the pyre: a Hårga member selected at random, or her boyfriend, Christian (Jack Reynor). While the entire film up to this point has highlighted Dani’s dependency on Christian (informed, in part, by the PTSD of losing her parents and sister in a murder-suicide earlier that year), she last saw her feckless lover having sex with another woman.

Burdened by this decision, not to mention hallucinogenic tea and the ongoing kairos time of complicated grief, Dani begins to breathe heavily underneath her floral caftan. Her face crumples. The camera then cuts to the Hårga preparing Christian for sacrifice.

All happy families are alike: Florence Pugh in the final scene of Midsommar (2019)

Sewn up in the skin of a disemboweled bear, he is the first living man to be hit by the flames, but is unable to move or scream. One of the Hårga men is able to cry out as the flames take over his body, screams that cue the villagers standing outside the temple to erupt in horrific shouts and screams. It’s an ecstatic display of empathetic mirroring. Dani, too, begins to cry and scream, but, in the final moments, something shifts within her. She pauses, considers the moment, and smiles.

It’s this moment, watching Midsommar one blazing July afternoon, that made me think of Callas. Midsommar’s story of a bad breakup has, for many, been interpreted as a happy ending; something that Aster doesn’t refute. “It’s designed to be cathartic. It's designed to play as a happy ending,” he acknowledged at a July 2019 Film Comment chat at Lincoln Center.

“It took a long time to get to the right place with the score for that last sequence… We were going for this lushness and this romance and this symphonic quality.”

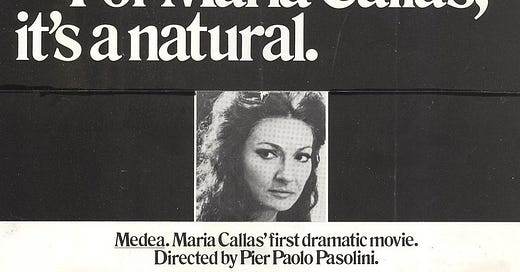

The symphonic quality Aster aims for can also be read as operatic, the catharsis he designed interpreted as primal. It’s evocative of another film that predated Midsommar by 50 years, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Medea. A champion of cinema in its most primal form, Pasolini’s retelling of the Greek tragedy starred Maria Callas, in her only film role as the eponymous sorceress.

The poster for Pasolini’s Medea (1969) knew exactly which myths it was selling to audiences.

However, the 1969 film Medea was far from Callas’s only outing with the role. She built her career in part on early and consistent success with Luigi Cherubini’s 1797 opera of the same name, a work she was central in “rediscovering” in the mid-20th Century. While Pasolini’s take doesn’t give her a single note to sing, the plots both revolve around Euripides’s drama: Medea, the granddaughter of the sun god Helios, abandons her “barbaric” home of Colchis to follow her dissolute husband, Jason, on to Corinth. When Jason leaves Medea and their two sons to marry the more “appropriate” Glauce, Medea enacts her revenge. After killing Glauce, she stabs her own children — and burns herself alive with her sons’ corpses.

While rarely considered against Callas’s voluminous discography, Pasolini’s Medea is one of the most definitive performances: for Callas, for Maria, and, in 1969, for angry women the world over. And the direct thread connecting Callas’s Medea to Pugh’s Dani is a prominent one in the grand tapestry of feminine rage.

That’s the story we’re going to look at today, moving from the myth of Maria, leading up to the point where personal and historical myth combined for Pasolini’s Medea, and how the echoes of that myth are felt in Midsommar.

In order to understand the significance of Callas’s film debut as Medea, it helps to consider three of the (many) rocky relationships that defined the diva’s personal life: her mother Evangelina, her husband Giovanni Battista Meneghini, and her lover Aristotle Onassis. All three of these relationships have already been dissected and mythologized, beginning in Callas’s own lifetime, so much so that revisiting any of them runs the risk of beating a dead horse without being able to further the narrative. Adding to the difficulty of parsing out these relationships is that Maria’s, Evangelina’s, and Meneghini’s accounts of history contradict each other — and, over time, themselves.

What seems to be consistent is this: Maria Callas’s debut on the world stage wasn’t well-received. In the first week of December 1923, somewhere between the 2nd and the 4th, Evangelina Kalogeropoulos gave birth to her third child at what was then Manhattan’s Flower Hospital. It had only been a few months since Evangelina, along with her husband George, landed in New York Harbor from their native Greece, their young daughter Jackie in tow.

It had also been a traumatic move for Evangelina, who was pregnant at the time (“All the way across the Atlantic, I was wretched,” Evangelina would later write in her 1960 memoir, My Daughter Maria Callas), and who hadn’t wanted to make the voyage. In her version of the story, George only told his wife to “prepare for a journey,” keeping her in the dark on his plans to start over in America until the day before they set sail.

Maria (second from left) with her sister Jackie, bookended by their parents Evangelina and George

This hadn’t been the first rift in the Kalogeropoulos marriage. Evangelina had even been warned by her father, General Petros Dimitriadis, not to marry the young medical student. “You’ll never be happy with him,” Dimitriadis said in one of his final conversations with his youngest — and favorite — child, who had once entertained dreams of becoming an actress. Two weeks after he died of a sudden stroke, the grief-stricken Evangelina and much-older George married on August 7, 1916. The couple moved to Meligalas and, the following year, Evangelina gave birth to their first child, Yakinthi (known affectionately as Jackie).

Unfortunately, George’s own ambitions fell far short of his young bride’s. While his pharmacy was a success, he didn’t seem to have any dreams beyond continuing to run the business and sleep with as many women as he could outside of his marriage. It’s possible that Evangelina minded the infidelity less than she did her husband’s lack of drive. If she couldn’t be an actress, she was going to be the wife of an important man; a man in the style of her own father. As her father’s prophesy played out, however, Evangelina was left with nothing else to do but swallow her pride and play the martyr.

By all accounts, George and Evangelina were at their happiest when their second child, Vasily, was born in 1920. Both parents took pride in their son, lavishing him with attention and praise. The happiness was short-lived: Vasily died either shortly before or shortly after his third birthday, either from a typhoid epidemic or meningitis (even Evangelina’s own accounts seem to vary from different sources). Regardless of the cause, Evangelina felt her heart die with her son, along with any hopes for turning the course of her marriage into a happy one.

All of this baggage made the journey to New York with the Kalogeropouloses (who eventually truncated their last name to the more Americanized “Callas”). The one hope Evangelina seemed to have then was that she was once again pregnant, which meant they would be able to replace the son they had lost. It never occurred to her that she might be carrying a daughter until that first week of December.

“Take her away,” the mother sighed when she was first presented with her newborn in the Flower Hospital.

Young Maria (left) with her mother Evangelina, and her sister Jackie

Maria’s parents seemed to be so apathetic about their newest additon’s gender that, throughout her subsequent life, her specific birthday remained unclear. Her godfather, Leonidas Lantzounis, recalled the day being December 2, which is always when Maria would celebrate. Her mother, however, insisted that it was December 4, believing that she had struggled with the labor for two days. Some biographers have theorized that, with their sights unflinchingly set on a son, George and Evangelina never completed the paperwork. They certainly hadn’t bothered to consider any girls’ names, but finally settled on “Maria” (Americanized to “Mary”).

A few years into their life in America, despite some success, tensions still ran high in the Callas house, culminating in the crash of 1929. When George was left with no other choice but to sell his pharmacy in Hell’s Kitchen in order to cover debts, Evangelina confronted him in the drugstore. Heading straight to the dangerous medicines cabinet, she grabbed a handful of pills and swallowed them — what Jackie would later describe as “her one and only personal appearance in an opera.” Evangelina survived, but the marriage didn’t. George took a job as a traveling salesman, and Evangelina began to control the narrative of Jackie and Maria’s father. In her 1989 memoir Sisters, Jackie writes:

“The entire Wall Street crash was pictured as a personal failure on the part of George Callas and indeed he did seem to be weak and uncaring about the whole thing. Only years later did I realize that there was nothing the poor man could have done.”

How Maria interpreted the tensions between her parents is largely undocumented. But Evangelina achieved total alienation from her husband in 1937 when she brought her girls back to Athens. The Callas sisters had both shown an early promise for music, and Evangelina was determined to see her great dream through. If she couldn’t be the wife of a great man, she would be the mother of a great daughter. Jackie had been the prettier one, slim and classically beautiful. But Maria, while myopic, olive-skinned, and chubby, had already won a few competitions. On the way to Athens, she even charmed the ship’s guests by singing the Habañera from Carmen, tossing a flower to the captain at the song’s climax.

“It's cruelty, I think,” Maria would later say of her early career start. “There must be a law against it. Children should not be given this responsibility. They don't last long. Children should have a wonderful childhood. I have not had this. I wish I could have.”

Adding a few years to her age so that she could enroll in the Athens Conservatoire, Maria began to study with Spanish coloratura soprano Elvira de Hidalgo, who remained grounded in Greece with the onset of World War II. As Maria mastered the art of singing from Hidalgo, she also, in Jackie’s words, “mastered the art of upstaging other performers, of using all the tricks that can win over an audience — and not merely onstage.” These lessons came from her mother's “lessons” in being selfish and temperamental, “which had given Mary an unflinching desire to get her own way at all costs. She had inherited the soldier’s genes from Mother’s family.”

After the War, Callas returned to the United States to audition for companies from San Francisco to New York. Encouraged to build her career in Italy, the soprano — still myopic, still overweight, and still struggling with her domineering mother — landed in Verona to make her debut in La Gioconda at the Arena di Verona in the summer of 1947. That summer was memorable for Callas, not only for this milestone in her career, but also because it was when the 23-year–old singer would meet the man who would become her husband, her manager, and effectively the replacement for Evangelina.

Like George Kalogeropoulos, Giovanni Battista Meneghini was much older than his future bride — more than twice Callas’s age when the pair met at a dinner in Verona. A man who made his fortune in brick manufacturing, Meneghini also considered himself an opera aficionado, and had a hand in the dealings of the Arena’s famed open-air summer opera festival. He had already tried to help jumpstart the careers of a few promising young singers who had passed through town, although nothing had come of it.

This track record would change in the summer of 1947, which was also the Arena’s first full season following the end of World War II. In Meneghini’s telling, the Arena’s music director, Tullio Serafin, suggested he have an official role during the crucial season. Meneghini joked that he could supervise the ballerinas, but Serafin apparently had other ideas. “You are a distinguished man,” he told Meneghini. “You should, therefore, have a prestigious job.”

Meneghini didn’t think Serafin was being serious when he then suggested that the businessman be the official escort for the two prima donnas making their debuts that season — Renata Tebaldi, who was already a known quantity in northern Italy, and another soprano who “hasn’t done anything of importance yet.”

“I didn’t have any desire to waste time escorting singers around,” Meneghini later wrote in his 1981 memoir, My Wife, Maria Callas. “At this time I was the head of a large brick-manufacturing business. Several of my factories were damaged in the war, and I was traveling constantly to make them operative again. I was working up to twenty hours a day, with scarcely any sleep.”

The next evening, Callas arrived in Italy and Meneghini was roped into attending a welcome dinner for her. He showed up halfway through the meal, reluctantly at Serafin’s urging. Too tired to eat a big meal, he told the waiter he’d just have a veal cutlet. Before the waiter could tell him that they were out, a voice from across the table said: “Sir, if you don’t mind, I would like to offer you my cutlet. It was the last one.”

Meneghini, who preferred a woman with curves to willowy ballerinas, was struck by the offer — and even moreso by the woman who made it. She was, he then learned, the singer who hadn’t done anything of importance yet. Maria Callas.

An undated photo of Callas and Meneghini, early in their relationship.

He must have liked what he’d seen that evening, because the next day, Meneghini brought Maria on a day trip to Venice. Against the cinematic backdrop of the Piazza San Marco, he learned more about the young girl’s unhappy life so far between her family issues and the hard years of the war. With money still tight, she had arrived in Italy with all of her belongings in a cardboard suitcase.

“When she spoke of her career and of her future, she didn’t have the enthusiasm characteristic of young people,” he would later recall. “She was sad, pessimistic. Her words were cold and a little bitter. They were those of a person accustomed to disillusionment, sacrifices, humiliations.”

Meneghini decided within those first 24 hours, before even seeing her perform, that he wanted to help Callas build a career. As he writes in My Wife, broaching this that day in Venice with Maria, he was

“…searching for the proper way to tell her, so as not to be misunderstood. I began by saying, ‘I’m interested in opera. I have already helped other young people. I am certain that you are gifted and can make a success of it. So, if you would allow it, I would also like to help you a little. Think about it, and don’t give me an answer now. I want you to have confidence in me.’”

Callas was apparently touched by this offer, and so Meneghini kissed her. The next day, Callas accepted Meneghini’s offer to help her out with her career, and “within a few days… our business agreement also became a perfect personal relationship.”

This is a line that Meneghini will repeat again, and again, and again throughout My Wife, Maria Callas. While the book was praised by the New York Times upon its publication in 1982 as the author’s “loving account of his life with a woman he never really knew,” that’s not necessarily the experience one has reading it in 2020.

Meneghini paints Maria either as overly devoted to her husband, or as a shrill hysteric — or both. Taking the place of Evangelina, most of his stories end with his own martyrdom out of sacrifice to her career, even brushing her hair and painting her toenails. His marriage to Callas, while constantly reiterated as happy — with just as frequent references to the “the dozens of letters and little notes that my wife wrote me,” is also presented as the event that fractured Meneghini’s own family.

Ultimately, he told his mother and siblings (who opposed the match) to “Take everything. I’m staying with Maria But remember that you will still need me.” A few years later the business Meneghini gave up for his wife had failed. He was, it seemed, still needed and intervened “so the losses would not be even worse.” But, he added, “now the great firm of the Meneghinis no longer exists.” He would go on to conclude: “The woman who revolutionized opera was also responsible for the rending apart and destruction of the Meneghini family.”

Maria as Cherubini’s Medea, Milan (1953)

Meneghini also takes credit for many of the actions that led to Maria’s castigation in the press. Through triumphant debuts, scandalous cancellations, and even his wife’s dismissal from the Metropolitan Opera over contract disputes with general manager Rudolf Bing, he takes the credit — but sidesteps the blame. In 1958, when she was fired by telegram from the Met, it was Callas’s name in the press, and her reputation, in BIng’s words, “for projecting her undisputed histrionic talent into her business affairs [that was] a matter of common knowledge.”

The night before she was fired from the Met, Maria had been at the dress rehearsal for Medea at The Dallas Opera, a rehearsal that stretched into 2:00 am. Her costar, Jon Vickers, described her process with the role as one of “masochistic intensity.” With the added fire from Bing, Callas’s performances of Medea in Dallas that year became the stuff of legend. But her firing from the Met was also a defining moment in Callas’s relationship with Meneghini, both as her manager and as her husband.

In retrospect, his account of his marriage (even the possessive nature of the book’s title), makes the affair read as though Maria replaced her mother with her husband. She would go nearly as far as to say this outright in later interviews. Unfortunately, these defenses also served to enhance an image of Maria as temperamental and difficult. The right photograph taken at the right time — such as her face when, still in costume as the title role in Madama Butterfly, she was served with a lawsuit from her former manager and couldn’t hide her anger — defied all explanations. Her vulnerability became a blood sport, one in which context was an illegal move.

The right photograph, taken at the right time, with no consideration for privacy or context.

“Battista only cared for money and position,” she would later say. “What can you do when you no longer trust your husband? I thought of Meneghini as a sheltering screen at first, to protect me from the outside world. And he did that, until my fame went to his head. Battista should have used more diplomacy in his negotiations with the theaters. His methods backfired, and I had to pay the consequences. That was the beginning of the end of our marriage.”

Maria’s decision to leave Meneghini after beginning an affair with Aristotle Onassis was like her father’s decision to move his family from Greece to the United States: Whether it was a complete surprise to Meneghini up until the day it happened, or there was a longer simmer, it nevertheless happened, and the ramifications of it were deeply felt by both parties.

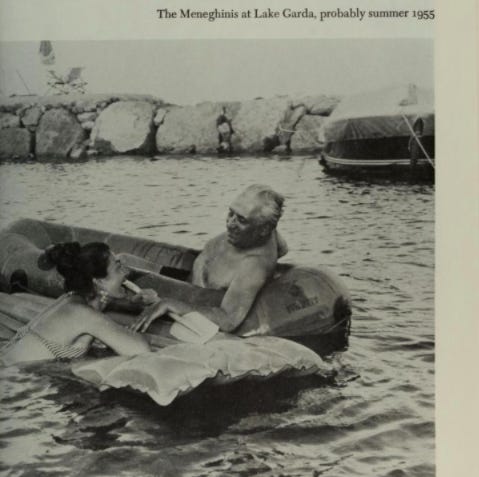

The Meneghinis and the Onassises had crossed paths prior to 1959. With the Greek-American Maria as one of, if not the most famous singer in the world and the Greek Aristotle as one of the richest men in the world, their circles were bound to overlap. But it wasn’t until Maria was once again singing Medea, this time in London, that Aristotle became a more constant fixture in her life, even going so far as to host a reception for her at the Dorchester Hotel after the production’s premiere at Covent Garden. Though not a fan of opera, Onassis was spellbound.

As a host, Onassis spared no expense, and his wining and dining of Maria and Meneghini seemed geared towards one-upping his fête at the Dorchester. His ultimate goal was getting the couple to join him and his own wife, Tina, on his yacht for a few weeks that summer, cruising between the Turkish and Greek coasts. Maria demurred, and following the run of Medea, she returned to Italy. The couple was in need of a break, and her doctor had suggested they get in some sea air, perhaps in Venice.

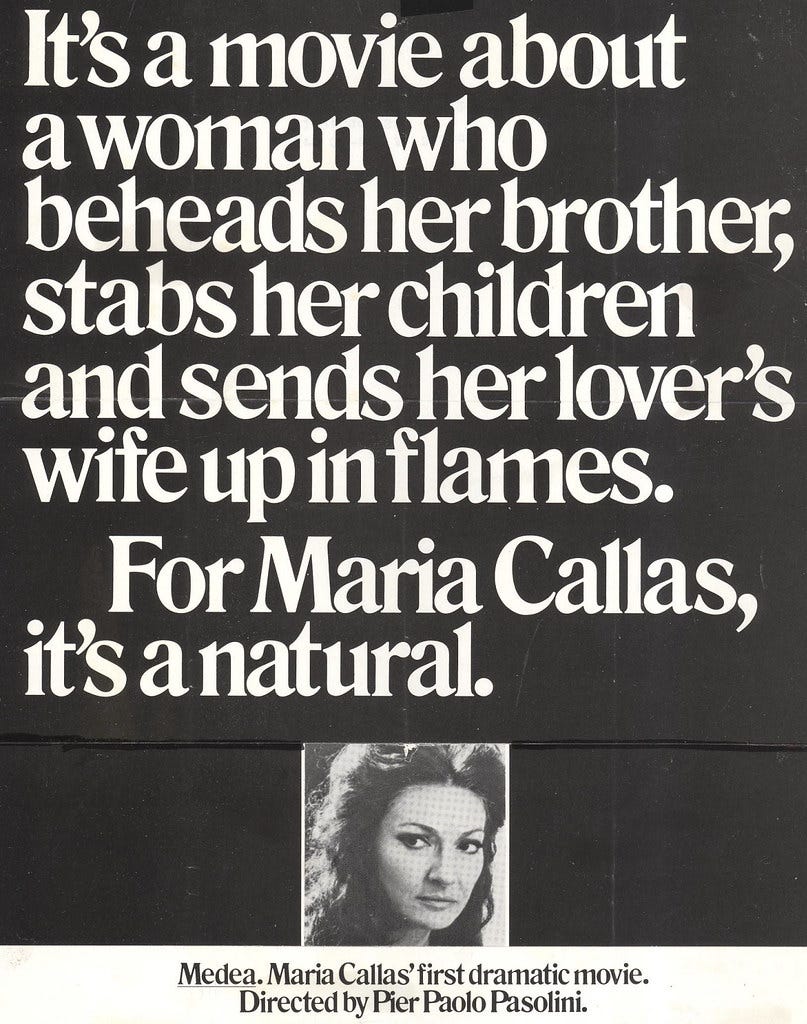

On July 16, however, Onassis called the Meneghini villa in Sirmione and asked to speak to Maria. “We are absolutely not here,” Maria told their housekeeper, Emma. Emma told Onassis that the couple was in Milan. Half an hour later, the phone rang again: Onassis had telephoned Milan and was told that the couple was at home in Sirmione. On the third try, Maria and Meneghini finally talked to Aristotle and Tina, and were finally talked into joining the couple on their yacht.

Meneghini recounts all of this in his book, under the chapter “How Onassis Robbed Me of Maria.” Their time on the yacht included traveling with Winston Churchill (who was “feeble and… incontinent”), Meneghini seeing Onassis in the nude (“He didn’t seem to be a man, but a gorilla”), and the Patriarch of Constantinople blessing both Onassis and Maria.

“I don’t know why he blessed them together. It almost seemed as if he were performing a marriage rite,” Meneghini wrote. “Maria remained profoundly troubled afterward. I could see it in her eyes, which were luminous and wild. When she returned to the ship that evening, I saw that she was totally changed.… It was that evening that the affair began.”

Maria remembers the evening differently. “I'm sure our friendship began there,” she later said. “I had found something I deeply needed and had never encountered before. He made me feel liberated and very feminine. I came to love him deeply.”

Much has already been written about the Callas-Onassis affair in the wake of that trip. Maria gave up her American citizenship in an effort to expedite her separation from Meneghini. Having made headlines the previous year as the first artist publicly fired by the Met, she was now in another strata of obsessive media coverage. Conflicting reports suggest, at turns, that Maria even became pregnant with Onassis’s child and either had an abortion at his behest or, as Nicholas Gage asserts in his 2000 book Greek Fire, gave birth to a son who died the same day.

And it’s at this part of Maria’s story that I grow most frustrated with the Callas myth. Without any of the original parties alive to set the record straight — and even with various parties trying to do just that in books that became more about self-aggrandizement than record-straightening — we’ve been left in the last few decades with former housekeepers and colleagues clamoring over abortions, secret births, and hysterical pregnancies. We’re left with a chorus of Internet commenters claiming with levels of conviction that border on zealotry that they know the truth, shouting in YouTube comments like so many self-appointed voices in the wilderness.

To borrow from a Nico Muhly quote I think about often, the various and sundry themes and variations on the truth in this story inevitably become exasperating. Figures like Evangelina and Meneghini vying for the narrative control of Maria’s life and legacy, combined with the supporting characters in her life, start to feel like so many ancient Greek squabbles, resentments, half-truths, good faith and bad faith arguments in the same sentence, and the occasional fling of incense.

Imagine how Maria must have felt living through all of it.

During her 9-year affair with Onassis, Maria continued to sing, although less frequently and, by many accounts, less well. “Changing my voice and technique during the performances did no good for my nerves, which were already strained after all these years,” she wrote to Elvira de Hidalgo in 1965. “Now my fatigue is endless, and my rage even more so for having crumbled like this.… The soul burns out, and the energy, too.”

And then, of course, Aristotle left Maria — in order to marry Jacqueline Kennedy. Maria was destroyed. After being painted as the tigress who had broken up Aristotle’s marriage to Tina, the diva was now painted as the vindictive ex while Onassis married a woman who had as much style as Callas, but was also famed for her poise and dignity, qualities the public persona of Callas seemed to lack.

“I am so lost, after so many years of work and sacrifices for one man, that I find myself incapable of knowing where to go,” Callas wrote to Hidalgo.

“I've given up a hell of a career, and it's too easy to say, ‘Oh, thank you very much.’ For eight years, nine years, we did our best to be happy,” she would say in a later interview. “‘Oh, ain't that sweet?’ as they say of all this. It's so easy to say no one is immature. Christianity says you must forgive, you must have no resentment. I don't have resentment, but I have hurt. How can I get rid of that? One last cigarette, and you drive me home?”

In Greek tragedy, the only thing comparable to exile is death — and even then, death is considered to be a more generous fate. For Maria Callas, exile had been a constant state for her, both physically and psychologically, since the beginning of her life.

She was born to a mother who, for the time she lived in New York, felt exiled from her homeland. By many accounts, she was exiled from her mother’s emotions unless she was performing. Having known nothing but Manhattan until she was 13, she then went into exile in Greece, just before the onslaught of World War II.

While she thought Meneghini would be a “sheltering screen,” he only increased her exile as she began her career, and in order to ultimately divorce him after she met Onassis, she renounced her US citizenship so that she could claim her marriage was invalid based on Greek Orthodox law. The ongoing issues she had with her voice were their own form of exile, a musician unable to control an instrument that was part of her body.

And then, in her new home in Paris, Maria was exiled from the one remaining good thing she felt she had.

It was the perfect time for her to revisit Medea.

Thanks for subscribing to Undone. Stay tuned for Part 2 of Maria, Medea, and Midsommar, coming to your inbox next week.

Further Reading

The following books are referenced in Parts 1 and 2 of “Maria, Medea, and Midsommar”:

My Daughter Maria Callas by Evangelia Dimitriadou/Evangelina Callas (1960)

Maria Callas: The Woman behind the Legend by Arianna Huffington (1980)

My Wife, Maria Callas by Giovanni Battista Meneghini (1981)

Maria: Callas Remembered by Nadia Stancioff (1987)

Sisters by Jackie Callas (1989)

Interviews with Maria Callas are largely credited to the following documentaries:

Callas: In Her Own Words by John Ardoin

Maria by Callas by Tom Volf

The history of Pasolini’s Medea comes largely from Stancioff, as well as:

Pier Paolo Pasolini by Stephen Snyder (1980)

Pier-Paolo Pasolini: Cinema as Heresy by Naomi Greene (1990)

Pasolini Requiem by Barth David Schwartz (1992)

Vocal Apparitions by Michael Grover-Friedlander (2005)

You can watch Medea in full on YouTube. I highly recommend it.