There was a moment from my interview with conductor Keri-Lynn Wilson earlier this summer in Lviv that has stuck with me. As we were wrapping up, Wilson (who had been impressed that someone without any familial connections to Ukraine would willingly travel to the country during wartime, as I have done a few times now), told me, warmly: “The world needs more of you.”

What immediately flashed into my head at that moment was Wilson’s husband, Metropolitan Opera general manager Peter Gelb, calling me (or at least my writing) “awful and nasty” in the New York Times about a dozen years ago. What a difference a decade makes. With this in mind, I jokingly responded, “I don’t think the world wants more of me.”

I thought of this exchange again while reading Gelb’s guest essay, “How to Save Opera? Make it New Again,” published on Sunday (also in the Times). “Many companies, including the Met, are still trying to recover from the losses of the pandemic. We are fighting to survive economically… regain our artistic footing and secure new audiences and donors,” Gelb writes, adding: “This is particularly difficult to accomplish because for decades there has been resistance to substantial artistic change from administrators, academics, and critics.”

What’s interesting to me in this sentence is that there is no mention of resistance from fans and audiences. While I’m certain I could find at least one critic who has argued for a sort of aesthetic revanchism in terms of repertoire and production values, I don’t think that is necessarily the point. I don’t feel any knee-jerk reaction to stand up for my fellow critics, nor do I harbor any protracted grudge against Gelb — I actually spent five years after that Ring-related meltdown working with a number of artists on the Met’s roster and enjoyed a good working relationship with the company.

Still, the idea that critics are to blame for the ongoing challenges of running the largest opera house in the country, particularly when it comes to making bold, artistic changes and the implication that we are the ones holding the Met back when it comes to new repertoire and productions, misses the mark.

If anything, critics have a history of arguing for even more bolder, more on-point choices. “This is an environment inhospitable to ideas or aesthetic conceptions,” Edward Said wrote in a 1986 issue of The Nation, in his review of Otto Schenk’s then-new production of Die Walküre. Contrasting the production with the world premiere of Anthony Davis’s X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X, next door at New York City Opera, Said added:

“Even if Davis’s opera wasn’t running concurrently with [Walküre] at the Met, I would still have found the Met’s relentless avoidance of the interesting and the contemporary exasperating. I am not speaking of the fact that 80% of the repertory is usually made up of La Bohème, Tosca, Rigoletto, Lucia di Lammermoor, Norma, and the like. What I am objecting to is the way in which the Met performs and reperforms the nineteenth-century repertory guided by a concept it seems to have borrowed from the opera sequences in 1930s Hollywood films — all the heroes and heroines are pudgy, loud, and stupid, the music they sing equally so. Inevitably then the avant-garde work of the nineteenth century is flattened into a semblance of its conservative counterpart.”

It’s a welcome change to Google Davis’s X and see, among the first image results, that of Will Liverman in the title role for the work’s 2023 Met premiere. But it didn’t take 37 years for the opera to travel from one corner of Lincoln Center to the other because of any reviews (the work even carried Beverly Sills’s imprimatur).

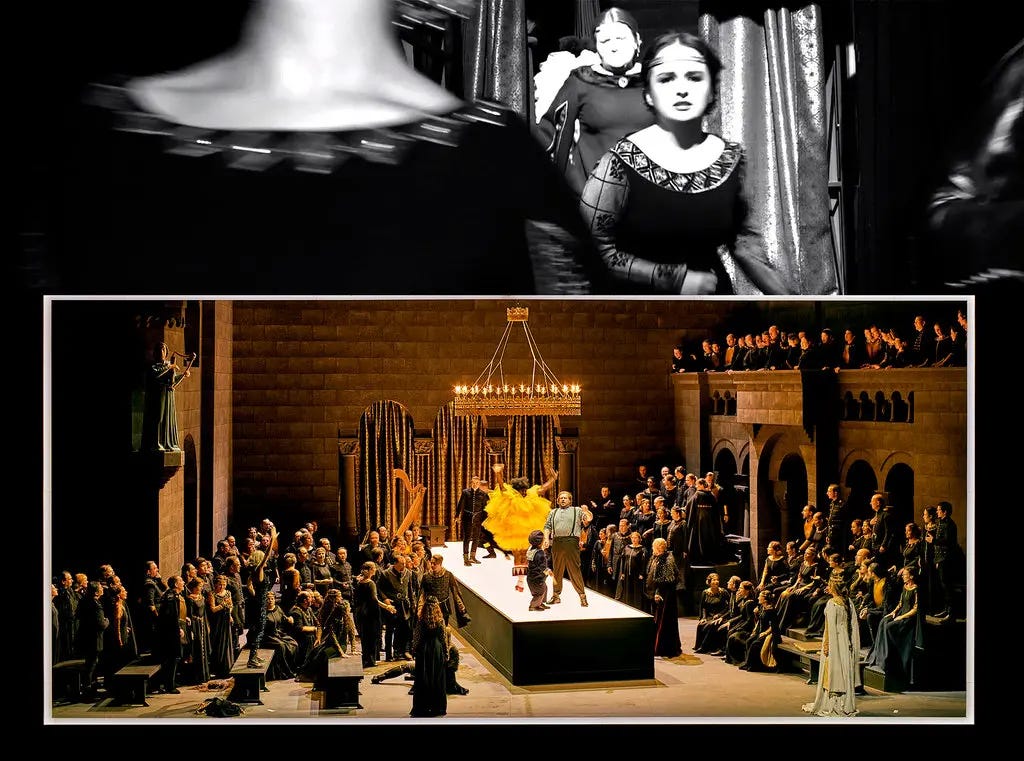

As Anne Midgette notes in her own response to Gelb’s piece, he took over the Met in 2006, promising vast changes, which in the early years largely hinged on bringing in theatre directors (Bartlett Sher, Mary Zimmerman) to “revitalize the art form” — which Midgette pointed out has “been a quite common practice since the early 20th Century.” Some of these productions were both critical and box-office successes, including Sher’s Barber of Seville and Anthony Minghella’s Madama Butterfly, which opened Gelb’s inaugural season. Others, like the Luc Bondy Tosca (which failed to deliver on its own promises of revitalizing Puccini’s work) or Robert Lepage’s misguided Ring Cycle (the finale for which may be the hardest I’ve ever laughed in an opera house), weren’t — but that’s a numbers game every company has to contend with.

In response, the Met has replaced some of its new productions under Gelb, many of which have retreated, once again avoiding the interesting and contemporary. Willy Decker’s stark and incisive La Traviata has been once again cosseted in a pretty-but-conservative production by Michael Mayer, one that ignores the avant-garde aspects of Verdi’s subject matter. Other revisits — Carrie Cracknell’s border-set Carmen, Simon Stone’s rustbelt Lucia di Lammermoor — promised to “reinvigorate” the classic stories (Cracknell’s words), but didn’t do much beyond changing the sets and costumes.

The effect was seemingly to have things both ways: a contemporary staging but with traditional gestures, a superficial nod to an idea that seems avant-garde but maintains a conservatism at its heart. Perhaps part of this, as Zachary Woolfe pointed out in his review of Carmen, was rooted in Cracknell and Stone both being non-American directors exoticizing middle America for urbane New Yorkers — a fetishization similar to that which compelled Bizet’s fellow Parisians to obsess over Seville and Roma culture. (That fetishization and of itself could have been an interesting meta concept for Carmen, similar to Tobias Kratzer’s Bayreuth production of Tannhäuser set in Bayreuth, but Cracknell didn’t seem interested in going that deep.)

Gelb is now arguing that the “wholesale change” he initially envisioned for the company began in 2020, when the company began to refocus on producing new works by living composers. That change is inarguable, and in many ways welcome.

But it’s also not necessarily radical when you consider the Met’s early years. Following its first world premiere of La fanciulla del West in 1910, the company gave a dozen other premieres in just that decade). It was responsible for bringing a lot of European works to the United States for the first time, including Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. It’s a good thing that the company didn’t put too much stock in the critical reception: “The tribute paid the opera and its performance last night was simply intended as homage to the rare characteristics of the music-drama and to the excellence of its representation,” read one review in the New York Times. “It had no further significance…we should not be surprised if Wagnerism, pure, simple, and exclusive as genuine Wagnerism must be, had said its final word in New York.”

Nor did it seem to tailor its performance schedule around another review from the same paper in 1918, describing the premiere of a new work as “something like a new Declaration of Independence, as far as concerns American opera.” That opera, Shanewis, was only performed nine times across two seasons.

Critics have never been the driving force behind what an opera company stages or how they stage it. That’s never been part of the job description. “As consumers of culture, we are lulled into passivity or, at best, prodded toward a state of pseudo-semi-self-awareness, encouraged either toward the defensive group identity of fanhood or a shallow, half-ironic eclecticism,” A. O. Scott writes in Better Living Through Criticism. Scott’s role of the critic was later summarized by Alex Ross as “to resist the manufactured consensus — to interrogate the successful, to exalt the unknown, to argue for ambiguity and complexity.”

I would add to this John Berger’s definition of a public critic. “Instead of identifying himself with the artist, [he] identifies himself with the spectator. He cannot consider the works in question as works in progress — a progress which his comments might influence; he must consider them as presented works and must try to evaluate them in relation to the world to which they have been presented.” If this function were better understood, he adds, “artists who expect press criticism to be ‘understanding’ would be spared much disappointment.”

My dog performing public criticism in Bayreuth (2022)

To me, this is where the Met has always been at a critical (as it were) disadvantage: A house built by New York’s 1%, it has remained largely as such for over 140 years. In some ways, Gelb has accomplished the most among his predecessors in his efforts to democratize the institution, expanding on discounted tickets, offering public access to final dress rehearsals, bringing broadcasts to satellite radio and international cinemas, and trusting his marketing team with leading a social media strategy that at times has fostered a genuine sense of community among many far-flung opera fans (despite the occasional misstep).

Yet the culture fostered within the opera house is still ruthlessly moneyed and exclusionary, despite steps towards the better, which makes it difficult for all but a handful of reviewers to connect between the world of the Met and the world of their readers. In my time reviewing Met performances during my 20s and early 30s, I had plenty of encounters with audience members that reflected this — including, during the premiere of Lepage’s Die Walküre, the gentleman seated to my left punching me during Act I. How was I meant to connect that to readers of Time Out New York, WQXR, or VAN?

It turns out, after a while, I wasn’t. Even before the pandemic, it became increasingly more difficult to get press tickets to the Met, even with a review commissioned, unless you were writing for one of several key media outlets (mostly legacy, mostly print). Even with those credentials, I know several journalists who were blocked from both season highlights (like Philip Glass’s Akhnaten) and even lower-demand runs like a standard revival of Boris Godunov. This seemed to also be a long-play on the company’s part: In 2012, Opera News announced that it would stop reviewing Met productions based on the company’s dissatisfaction with negative coverage (that decision was later reversed).

“Saving” opera (such that it needs to be saved) cannot happen in isolation, nor can it be selectively saved. Doing this will only ensure that it continues to be preserved for an elite few, and need to be saved again once they drop off or move on. But, of course, that’s just my opinion.