Welcome to Part 1 of Six Degrees of Plácido Domingo, where we’ll be exploring opera’s current #MeToo reckoning through four centuries of misogyny and misconduct in the genre’s history — onstage and off.

To understand the relationship between sexual politics and opera, it’s not an exaggeration to say we should start by revisiting the birth of opera at the end of the 16th Century. We now know that there were cities all over Italy (and beyond) that were experimenting with musical theatre, building off of medieval liturgical plays and the intermezzi that punctuated otherwise spoken plays in the Renaissance.

But history is written by the victors, and few families “won” the Renaissance as much as the Medici. At the beginning of the Renaissance, circa 1300, they were a respectable but hardly-aristocratic family. By the end of the era in 1600, they were one step below royalty, with many of their descendants marrying into royal families. To talk about power, however, is to talk about sex. And the function of women (which was, effectively, their ability to procreate) led the gender to become an effective economy, one in which the Medici family was a keen player.

Venera Gimadieva as Marguerite de Valois, daughter of Catherine de’Medici and cousin of Maria de’Medici, with John Osborn as Raoul, in Les Huguenots at the Dresden Semperoper. (Photo: Daniel Koch)

The financial and sexual utility of Medici women was critical for building the family’s financial and political dynasty. Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici, who founded the Medici Bank in 1397, was able to do so in part thanks to his wife, Piccarda Bueri, and her dowry of 1,500 florins. The conversion rate varies, but today’s US dollar equivalent could be as high as $1.5 million.

Also critically, Piccarda also gave Giovanni two sons: Cosimo and Lorenzo the Elder. Cosimo continued to climb the ladder, ultimately being posthumously dubbed “Pater Patriae,” the father of his country. (That the citizens of Florence also rejoiced on Cosimo’s death only speaks to the truthfulness of his title: “Who is simultaneously loved and resented if not a father?” writes historian Tim Parks.)

Cosimo’s ascension was thanks in part to his marriage with the Contessina de' Bardi. Her dowry was more modest than that of her mother-in-law’s, but that financial shortfall was made up for with the windfall that came with marrying a Bardi. It wasn’t a love match. The Contessina was uneducated and by some accounts unattractive and dull. Cosimo kept busy outside of Florence. But this didn’t mean that the marriage was unhappy. He had his job, she had hers, and the working relationship was smooth.

While noblewomen could be an asset with a high market value as they reached child-bearing age, their primary purpose was to produce heirs. Male heirs. After having three daughters, Cosimo’s daughter-in-law, Lucrezia Tornabuoni, was delighted to finally give birth to a son, who would become known as Lorenzo the Magnificent. The golden child of his family, Lorenzo’s ultimate marriage was an obsession for Lucrezia, who raised him to seduce, both romantically and politically.

As Lorenzo studied and partied in Milan, his tutor would report back to the family that their golden boy “stays out late, flirting with the girls.” Historian Francesco Guicciardini described Lorenzo as “all libidinous and venereal.” Niccolò Machiavelli, who would dedicate his most famous work, The Prince, to another Lorenzo de’ Medici (Lorenzo di Piero), concurred that he was “marvelously involved in things of Venus.”

He counted among his love affairs Ippolita Sforza, who would go on to marry King Alfonso II of Naples, and Lucrezia Donati, the subject of many of Lorenzo’s early poems and a woman he continued to love after his marriage to Clarice Orsini in 1469.

Not present at this wedding was Clarice herself. The marriage was held by proxy, with Clarice still in Rome. But Lorenzo’s party still managed to run up a 10,000 florin tab. As the Medici Bank began to stagnate and buckle under Lorenzo’s watch, the family’s import-export business of women continued, and stocks truly began to appreciate on the other branch of the family, launching the Medici name into the aristocracy. To call the local network of Florentine nobility incestuous reached new meaning when the branches that grew from Giovanni di Bicci’s two sons intersected at the altar. Lorenzo the Magnificent’s own granddaughter, Maria Salviati, married the great-grandson of Lorenzo the Elder, Ludovico de’ Medici, rechristened Giovanni delle Bande Nere. (For those keeping score among all of the Lorenzos, this would mean that Maria married her third cousin.)

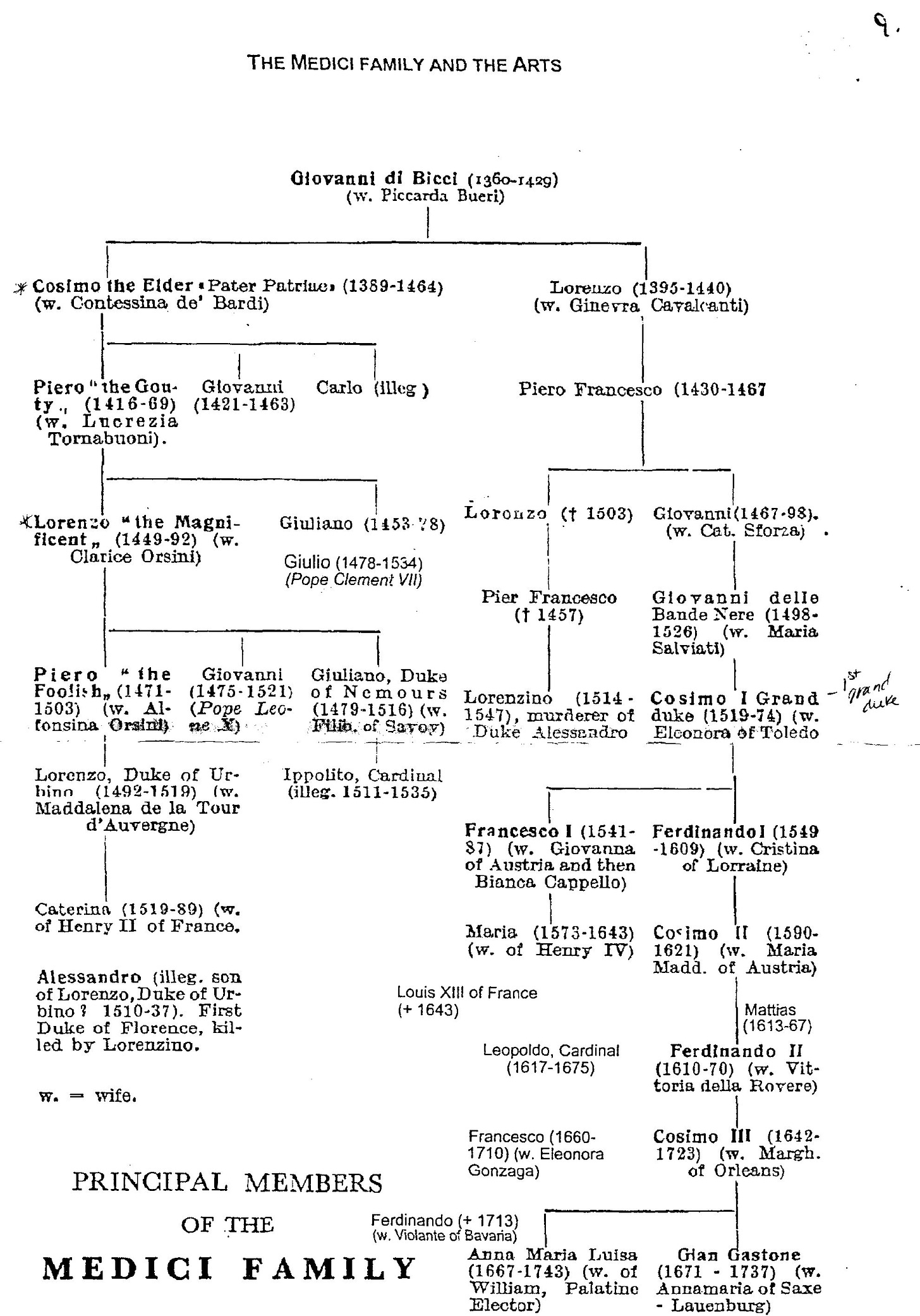

Principal members of the Medici family, via USF College of Education

And it’s with the son of Maria Salviati and Giovanni delle Bande Nere that the story of the first surviving opera — and its place in a network of sex and power — really begins.

The Medici were longtime arts supporters — Cosimo the Elder began diversifying Florence’s musical scene in the 1430s, and Lorenzo the Magnificent's court counted among its artists Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli. For the Medici, as with families like Koch and Sackler today, it wasn’t enough to support art, but to be immortalized through it. Many of Botticelli’s paintings contain illusions to Lorenzo the Magnificent, as well as his father, uncle, and grandfather. And with Cosimo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany (born in 1519), commissioning music became a matter of course for celebrating family and state occasions. This began with Cosimo I’s 1539 wedding to Eleanor of Toledo, which included a set of compositions written specifically for the occasion (including music to accompany a play).

This is often pinpointed as one of the main originators of opera. What we now know about the genre, as with many art movements in history, Florence wasn’t the sole point of origin of opera. Music and theater had gone together in the preceding era with medieval passion plays, and even the concept of opera came out of the belief that ancient Greek tragedy was at least in part sung through (a tradition that may have come from Greek occupation of ancient Mesopotamia).

Yet while many artists around Italy were experimenting with similar innovations that gave way to form, critical to Florence’s central place in opera’s history was Count Giovanni de’ Bardi. Born 15 years after Cosimo I, Bardi came from the same lineage that married into the Medici family in the 1300s with Contessina de' Bardi. Giovanni de’ Bardi fought under Cosimo I, including the 1553 war against Siena. Perhaps in part due to such loyalty, Bardi married Lucrezia Salviati, Cosimo’s first cousin.

It was around this time that Bardi also began to more seriously patronize the arts. He arranged for lutenist Vincenzo Galilei (Galileo’s father) to study composition in Venice. He also saw promise in a young tenor named Giulio Caccini, whom he came to support financially through sponsorship. Bardi’s son Pietro remembered his father’s house as one that was full of thinkers, poets, scientists, and musicians.

As early as 1573, one of these meetings (which most likely involved both Galilei and Caccini as well as Jacopo Peri) turned to music and the Greeks. Surviving letters between Bardi, Galilei, and historian Girolamo Mei, discussed questions that Galilei had about Greek theory, as well as the current state of musical affairs. Many of the core values that resulted from this exchange were later published in by Galilei in 1581 as the Dialogo della musica antica et della moderna, or “A Dialogue between Ancient and Modern Music.”

Central to the Dialogo is the principle that music was not only a form of entertainment, “but also useful to virtue to those who were born to achieve the perfection and the human bliss, that is the purpose of the state.” Assuming that “whoever has a mind not entirely purged of every passion cannot give perfect judgement of anything that exists,” Galilei then turns to Aristotle’s definition of tragedy as a means of achieving this purge. In short, music, done well, should be a means of catharsis.

Galilei’s Dialogo, and its exploration of catharsis achieved through art, is essentially the manifesto of the Florentine Camerata (a name posthumously affixed to the group by Caccini). And the philosophy of the era was something that Bardi actively participated in, in addition to financing the work of his peers. This support was aided in part by Bardi’s fortunes being tied up with those of the Medici, particularly Cosimo I and his eldest son, Francesco I.

Much in the same way that Bardi is now seen as the original financier of opera, Cosimo I used his power to make Florence a center of the arts, most notably by financing what would become the Uffizi Gallery. But Cosimo was also a ruthless autocrat whose rule was made possible by the assassination of his cousin, Alessandro de’ Medici. A noted womanizer, Alessandro was lured into a rendezvous by his distant cousin Lorenzino. Lorenzino then assassinated Alessandro in an attempt to launch a coup. This ended the main branch of the Medici dynasty — stretching back to Cosimo the Elder — as Alessandro had no legitimate heirs. But it also gave Cosimo I the unexpected chance to rule. He wasn’t a popular choice, but as historian Paul Strathern notes, the people of 16th-century Florence needed some stability after centuries of Medici drama, and Cosimo was able to offer that. For a price.

This period of stability came in part, as Nicholas Scott Baker suggests, through gender roles and views of the time and some efficient propaganda. Alessandro’s reputation as sexually voracious (much like his predecessor Lorenzo the Magnificent) meant that he also was known to spend time with women. This was used against him as a man who, by virtue of being a womanizer, spent more time with a “weaker” sex and less time with his fellow men. Perhaps ironic for today’s audience, this association brought not only Alessandro’s heterosexuality and masculinity into question, but also his ability to govern.

Cosimo, on the contrary, created an image of uncomplicated monogamy to Eleanor of Toledo, to the point of ostentatiousness in Baker’s view. This, along with his “open campaign to punish sexual crimes,” created an image of him as vir virtutis, a man completely in control and in power. That this image was in part due to Cosimo’s own manipulations and public relations should not be overlooked, and is especially worth taking into context against the way that images are shaped and controlled today (especially in conjunction with the public image of Plácido Domingo).

If only out of a sense of familial duty, Cosimo patronized the arts, and the might of the Uffizi has stood in for a more complete, at times damning, image of him to the people who visit Florence every year. Yet in his time, he was better known as an autocrat. Sure, he was the Medici responsible for giving Florence the Uffizi Gallery, but it — along with the Palazzo Pitti and Boboli Gardens — was bankrolled through high taxes of average Florentine citizens.

The legacy of the Uffizi building itself is a revealing metaphor of the strange bedfellows that are art and politics: Translated as "the Offices," the gallery was originally a building erected by Cosimo as an administrative headquarters for the various properties he had consolidated and controlled. (Just a few hundred meters north of the Uffizi Florence’s central square, the Piazza della Signoria. Overlooking it is a statue of Cosimo, erected by the sculptor Giambologna 25 years after the Duke’s death. It’s hard to find a statue that lived an unproblematic life.)

When Cosimo I died in 1574, the Camerata was just beginning to take shape. Yet Bardi was able to keep favor with Cosimo’s successor, Francesco I, who had been serving as regent for his father since 1564. Much like his father, Francesco also ruled with a Machiavellian fist. Unlike his father, however, he gave no illusion of faithfulness to his wife, Joanna of Austria (whom he married in 1565).

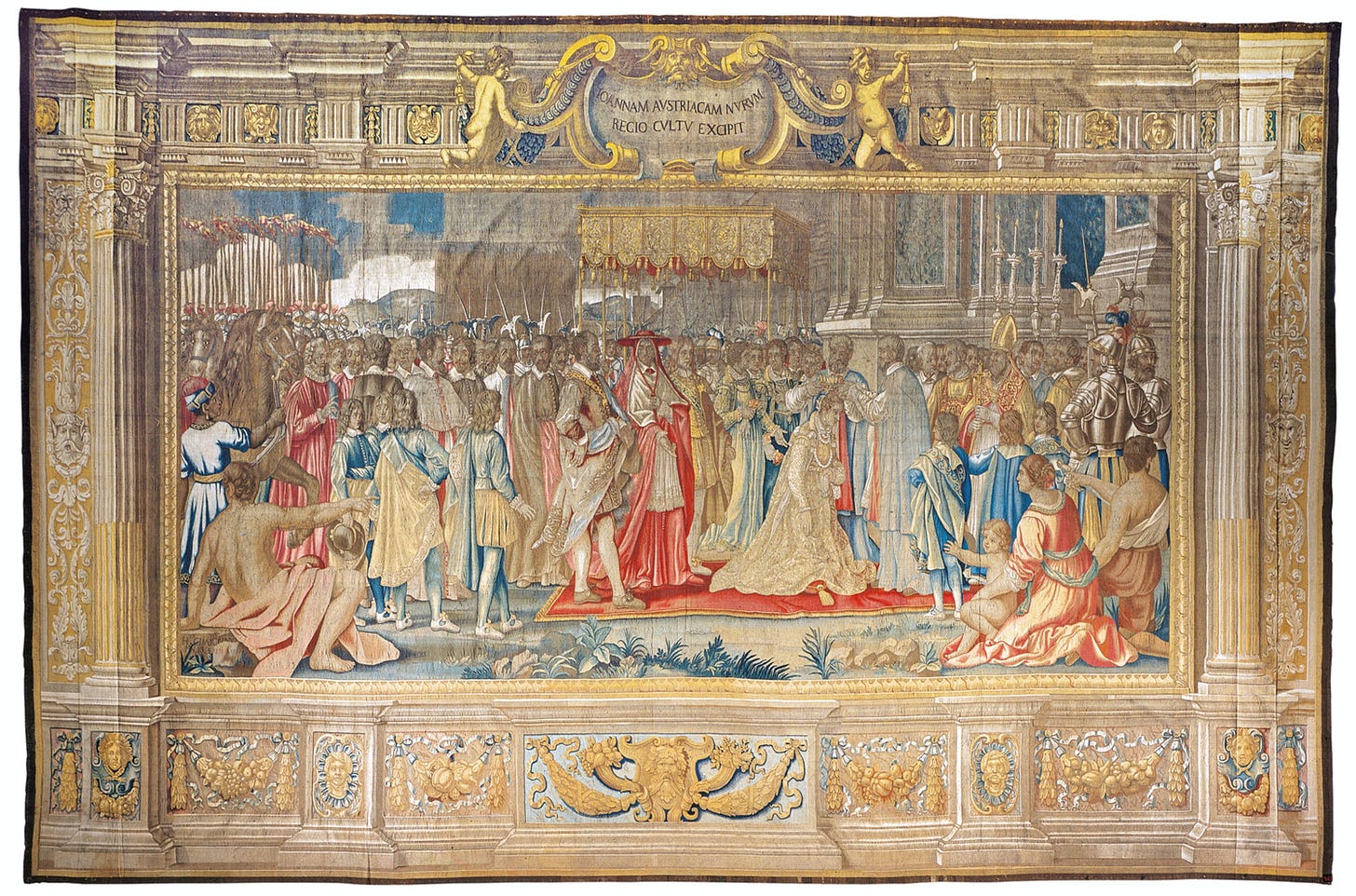

The youngest daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I and Queen Anna of Bohemia and Hungary, Joanna was (to quote Catherine Ferrari) “the most prestigious match that the Medici had ever made.” Brokered fastidiously by Cosimo I, the marriage tied the family to the Habsburgs in central Europe, and was so monumental for the Medici that it is one of the events immortalized in a series of tapestries hanging in the Uffizi today.

A 17th Century tapestry commissioned by Ferdinando II de' Medici, depicting the coronation of Joanna of Austria at Porta al Prato (Source: Uffizi)

For his part, Joanna’s father took care with arranging the marriages of his daughters (of which there were many), not only with concern for politics, but for his children’s happiness. Quoting Paula Sutter Fichtner, Ferrari notes that Emperor Fedinand “took the procedure of gaining the consent of his daughters to the unions he contracted for them very seriously.”

Yet the marriage of Joanna and Francesco was unhappy from the onset. Adding insult to injury, a lack of available information on Joanna effectively gaslit her for centuries. Painted as cold and stuck in her ways, unable and unwilling to adapt to Florentine custom, Joanna’s legacy has been that she was complicit in her own unhappiness. Based on recently-discovered letters, however, this is an unfair portrayal, perhaps even more image management via Medici hegemony.

Despite Emperor Ferdinand’s best efforts, not every royal marriage was a success for his daughters. This had proven true with Joanna’s eldest sister, Elizabeth, when she married Sigismund Augustus of Poland in 1543. Sigismund’s mother, Queen Bona Sforza, angry at Emperor Ferdinand over a land dispute, took out that anger on her daughter-in-law, who died after one year of marriage.

Joanna’s Habsburg roots were a constant source of irritation for Francesco, who saw his wife’s support of German citizens living in Italy as tantamount to supporting the enemy. It was originally Joanna’s brother, Maximilian II, that Cosimo had been lobbying for the title of Grand Duke, before he turned to the Pope for help. Yet Joanna sided with her brother in his hesitation, even though it would affect her own title, as well as the titles of her children.

When Cosimo married his mistress, the commoner Camilla Martelli, Maximilian objected to his sister:

“I cannot much wonder what the Duke was thinking when he made such a shameful and unpleasant match, for which he is mocked by everyone. The good Duke must not have been himself.”

Upon reading the letter to his daughter-in-law, Cosimo responded, “when need be I will show him that I am in my right mind.” He then reminded Joanna that she was now a Medici, no longer a Habsburg, and should realign her loyalties accordingly. In one letter that Joanna wrote to her father, a letter presumably dictated to her by her husband based on the requests she makes, we can still infer something of her true feelings with this opening sentence:

“When I thought I was the happiest woman in Italy, I instead find myself to be the unhappiest alive.”

Two years before his death, aware of both his daughter-in-law’s unhappiness as well as the fate that her sister Elizabeth had suffered in Poland, Cosimo tried to counsel Joanna in an attempt to salvage the match he had brokered:

“[I]f Your Highness would consider your sisters, perhaps you would be happier with your own condition than you are now, for I know how some of them, and more than one, have been treated.”

In retrospect, this advice reads more like a threat. Relations between Joanna and Francesco only grew worse after the death of Cosimo in 1574. By that point, Joanna had given her husband 5 children, but they had all been daughters. Her sixth child, delivered the year following Cosimo’s death in 1575, was also a girl — Maria. Despite Joanna’s involvement in state affairs and international relations, a job she took seriously, her “real” job was still not being carried out: She needed to give Francesco a son. She finally did this in 1577, but technically it would be Francesco’s second son. His first was born to his mistress, Bianca Cappello, the year before.

Shortly after his father’s death, Francesco installed Bianca (whose own husband was murdered in the streets of Florence in 1572, an act connected to Francesco) in a palace on Via Maggio. Where he tired of Joanna, Francesco doted on Bianca. The threat that their son posed to Joanna was also real: She could easily be banished, her husband’s illegitimate son legitimized, and eventually made the next Grand Duke.

At the same time, two of the Medici women closest to Joanna suddenly died: Her sister-in-law Eleonora di Garzia di Toledo, was strangled by her husband, Francesco’s brother Piero. A few days later, Francesco’s sister, Isabella, died on a hunting trip. The circumstances are murky, but many believed it to be at least supported by her own husband, Paolo Giordano Orsini, and Francesco. Joanna’s brother Ferdinand, Archduke of Tyrol, considered removing her from Florence by force, incensed that his brother-in-law’s mistress was “held in greater regard than an Archduchess of Austria.”

Unlike his grandfather, however, the new emperor Rudolf II (son of the now-deceased Maximilian II) was reluctant to prioritize his aunt’s happiness over a key political alliance. Joanna’s brother Ferdinand was resigned:

“If the Prince of Florence does not wish to love and treat his [Ferdinand’s] sister with that love and marital loyalty that is befitting,” he wrote, “we Austrian Princes cannot in good conscience do other than commit everything to God.”

This decision had fatal consequences: On April 10, 1578, Joanna, pregnant now with her eighth child, fell down the stairs of Florence’s Grand Ducal Palace. The fall sent her into premature labor. The next day, the baby was delivered a stillborn and Joanna died leaving many to believe that the “accident” was set up by Francesco and Bianca. Had Joanna’s child lived, he would have been her second son. Filippo, similarly, wouldn’t live to see the throne: He suffered from hydrocephalus and died shortly before his fifth birthday in 1582.

In short order, Francesco legitimized his son with Bianca and married her almost immediately after his first wife’s funeral. It was a divisive move; one that many people, including Francesco’s own brother, Ferdinando I, objected to, while others, like Bardi, publicly supported the couple. The debate over morality was a short-lived one, however. Five years later, Francesco died. Bianca followed suit after 24 hours. The official death certificate noted malaria in describing the cause, one that many Florentines debated, suggesting that the pair were poisoned by Ferdinando (or perhaps a rogue Habsburg). In 2010, a forensic study put this conspiracy to rest: Francesco’s remains had traces of plasmodium falciparum, the parasite linked to malaria.

Ferdinando, a Roman Cardinal, returned to Florence after the death of his brother and sister-in-law and took over the role of Grand Duke of Tuscany. While Bardi would outlive Francesco by 25 years, his fortunes in Florence severely diminished with the era of Ferdinando given their differences of opinion over his second marriage. And while the heyday of the Camerata had come to a close by 1582, the products of the group’s labors were still to come.

The first surviving opera is linked to this, as well as another unhappy Medici marriage. Left essentially an orphan by her 12th birthday, Maria de’ Medici was still a Medici (and a Habsburg), and Ferdinando provided for her as she grew into maturity.

By the time this happened, the daughter of Queen Catherine de’ Medici of France (Alessandro’s half-sister) was dealing with a crisis: Margaret of Valois, had married Henry IV, but after nearly three decades produced zero heirs and one unhappy marriage. This hadn’t been as much of an issue in their early years as a couple; Good King Henry kept busy with mistresses (including Gabrielle d'Estrées, who had three of his children out of wedlock). Margaret herself found the marriage more tolerable when she moved into a separate castle in 1589.

But Henry IV went from being King of Navarre to King of France when the last of Margaret’s brothers, Henry III, died in the same year. Henry originally sought an annulment of his marriage so that he could wed Gabrielle and legitimize their children as heirs to the throne, but then Gabrielle herself died in giving birth to a stillborn in 1599. Margaret and her relative Ferdinando I saw an opportunity for a solution that would leave Margaret deposed, but would preserve the Medici influence at French court: Margaret would accept an annulment, if Henry promised to marry Ferdinando’s niece, Maria. The couple were married by proxy the following year.

In his reign, Ferdinando turned out to be a more benevolent ruler than his father or brother, reforming the Florentine justice system and reducing taxes. In taking care of his niece (who would become Marie of France), he not only helped to arrange the match, but also sponsored a wedding celebration in Florence included the debut of a new work by composer Jacopo Peri, Euridice (a wedding present from one of Florence’s chief patrons, Jacopo Corsi).

Peri’s take on the tale of Orpheus, with additional input from Caccini (who wrote his own operatic adaptation of the story), stemmed from the work and theory of the Camerata, fusing drama and music to create a form of storytelling. Orpheus and Euridice, the story of a musician rescuing his wife from the underworld, was a natural fit for many of the initial operas’ libretti as it gave logical dimension to the use of sung text.

The world premiere of Euridice took place in the Palazzo Pitti, Cosimo I’s gift to Eleanor of Toledo, and the occasional home of the bride’s illegitimate-then-legitimate half-brother. The plot of the opera, however, took on one critical change: In the original telling of the myth, Orpheus loses Euridice before they leave the underworld when he disobeys the crucial rule that he must not look at her before they re-enter the world of the living. Unable to overcome his own hubris or doubt, Orpheus breaks this rule and re-condemns Euridice to the underworld

In Peri’s version, however, the rescue mission is a successful one. What else would one expect of an opera meant to celebrate a royal wedding? Anything more damning may have called to mind Maria’s own mother and her fate.

In making this change, Peri also laid a crack in opera’s foundation. For an art form that came from the noble idea of using tragedy as catharsis, the first surviving work shows that opera would continue to struggle with catharsis over commerce, function over form. Like the Medici women before her, like many women after her, Euridice was a means to an end.

Thanks for subscribing to Undone. Next week: Six Degrees of Plácido Domingo, Part 2: Casanova and Da Ponte: The Lives and Afterlives of Don Giovanni.

Further Reading and Listening

Ensemble Arpeggio’s recording of Peri’s Euridice can be heard on YouTube

Les Arts Baroques’s recording of Peri’s Euridice can be streamed on Spotify

“Kinship and the Marginalized Consort: Giovanna d’Austria at the Medici Court” by Catherine Ferrari in Early Modern Women (2016)

A History of Opera by Carolyn Abbate and Roger Parker (2012)

“Power and Passion in Sixteenth-Century Florence: The Sexual and Political Reputations of Alessandro and Cosimo I de' Medici” by Nicholas Scott Baker in Journal of the History of Sexuality (2010)

Medici Money: Banking, metaphysics and art in fifteenth-century Florence by Tim Parks (2005)

The Medici by Paul Strathern (2003)

Dialogo della musica antica e della moderna by Vincenzo Galilei (1581)