Welcome to the concluding chapter of Six Degrees of Plácido Domingo, where we’ve explored opera’s current #MeToo reckoning through four centuries of misogyny and misconduct in the genre’s history — onstage and off.

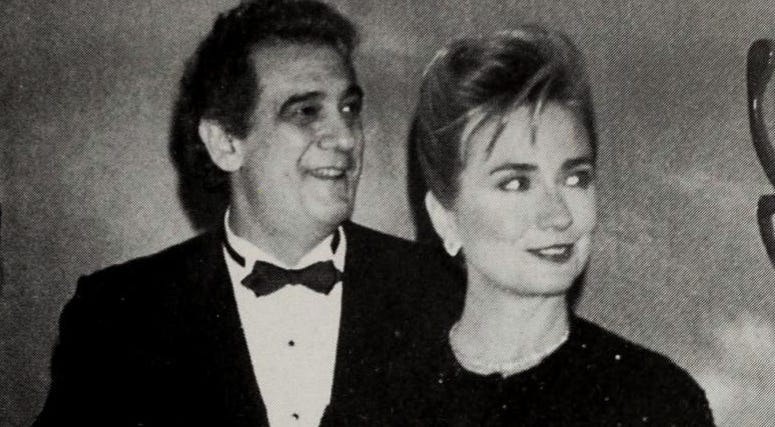

Plácido Domingo and Hilary Clinton, in an undated/uncredited photo published as part of The Private Lives of the Three Tenors (1996)

First, a moment to recap: Opera came together in part thanks to the court of a Florentine nobleman related to the Medici dynasty. The first surviving opera, Peri’s Eurydice, was written especially for the wedding celebration of Maria de’Medici to King Henry IV of France. The genre began to take off, reaching an international golden age during the 18th and 19th Centuries.

Works from that era are still heard today, including Mozart’s Don Giovanni (whose text was inspired by, if not directly edited by, librettist Lorenzo da Ponte’s friend, Giacomo Casanova), and Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor (which epitomized the early 19th-century tradition of …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Critical Drift to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.