To say that the 1960s were a rough decade for the Metropolitan Opera would be an understatement. In the summer of 1961, the company faced one of its greatest labor disputes, which included struggles with its orchestra’s union over both fair compensation for long rehearsals and nonstop performance schedules, as well as control over hiring and firing of orchestra members.

In his second decade as the company’s General Manager, Sir Rudolf Bing began to lock horns more than ever with the Met Orchestra, who were frustrated with working more than their colleagues in symphony orchestras (which averaged about three performances a week) for less compensation. This was by no means new in 1961 compared to 1916, but, as Johanna Fiedler notes in her history of the Met, Molto Agitato, the ‘60s marked a crucial shift in Met orchestra personnel. They now had more musicians who were American versus European, and, by comparison, the Americans were more willing to stand their ground at the expense of art.

Meanwhile, Bing was Austrian native who grew up in Vienna during the early gilded days of the 20th Century. In New York he was, in the words of critic Tim Page, “an impresario right out of Central Casting… who rarely ventured out without his bowler hat and umbrella. Deeply conservative and proudly Eurocentric in his tastes.” The culture clash between Bing and his orchestra was inevitable. In one tense negotiation session, the orchestra’s attorney asked if the impresario was trying to show his contempt. “On the contrary,” Bing replied. “I am trying very hard to hide it.”

Things became so bad that the Met’s board requested a “no-season” budget for 1961-62. A mediator brought in from the Department of Labor recommended closing the house for a year, the equivalent of a couple’s counselor suggesting divorce (or at least a trial separation). It took President Kennedy to intervene and keep the lights on for that season, but this struggle set the tone for a decade that became even more complicated — if not outright traumatic — with the company’s move to Lincoln Center in 1966.

Progress on the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, as seen in Susan Froemke’s The Opera House

The new Met made up for many of the shortcomings of the old house on 39th Street, offering better views for the audience, more space behind the scenes, and the latest in technology (Franco Zeffirelli, who would direct the opening performance of Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra, called it “a Cadillac”). But the piper doesn’t work for free, and the move was also an enormous financial undertaking, with foreign investments helping to cover the costs of the new backstage area.

Even after the building was completed, the cost to run the company would almost double from $4 million a year to nearly $8 million in 1966 dollars (the 2020 equivalent would be roughly $32 million and $64.5 million, respectively). And, for all of its features, the house’s technical bugs began to reveal themselves in the rehearsals for Antony and Cleopatra. The house-opening production was itself an artistically and financially ambitious undertaking, with a cast of over 400, a live elephant, and a faulty turntable that, after its girders snapped from the weight placed on it, required nine men, fifteen pairs of sneakers, and one conductor inside to power it for performances.

For a night that should have been a triumph, Antony and Cleopatra became one of the Met’s greatest flops (it hasn’t been seen on the Met stage since its critically-panned premiere). The deficits of running at Lincoln Center also forced Bing to increase ticket prices mid-season by 20%. The board also launched a $3 million Emergency Fund Drive which succeeded in terms of dollars, but failed in the court of public opinion. What the Met really needed in a time like this was an endowment, which it lacked. People were generally clamoring for subscriptions and jockeying for board positions in the company’s first 85 years, so an endowment never seemed to be necessary. The Met was essentially the Bluth family, now realizing that they needed to both make up for their deficit and set up a safety net for the future, but still assuming that a banana cost $10.

Bing had another adversary in this era, board president Anthony Bliss. While Bing kept dachshunds and vacationed in Italy, Bliss kept horses and had a ranch in Montana. The two had worked at cross-purposes for most of the decade, until Bliss resigned as board president in 1967 in order to finance a divorce and a new marriage to a Met ballet corps member nearly half his age.

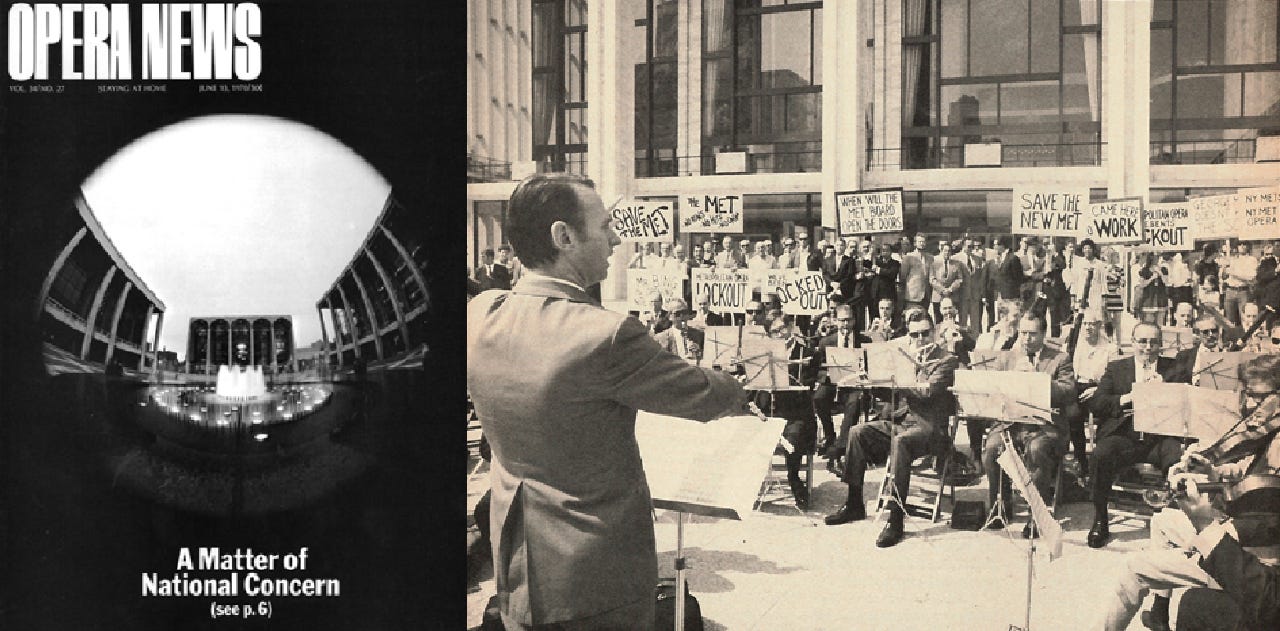

Opera News’s coverage of the Met’s 1969 lockout

Two years later, the ‘60s closed with an event that had been anticipated at the beginning of the decade: Following more labor negotiations in the summer of 1969, Bing postponed opening night “indefinitely” for the 1969-70 season, creating a three-and-a-half month lockout that kept the Met dark until late December.

Bing’s assumption is one that’s familiar to arts audiences in today’s international pandemic: While performances had been cancelled, he hoped that subscribers would forego their refunds and, instead, treat the loss as a (much-needed) donation to the Met. At the time of the lockout, the total pre-season subscription sales were $2.85 million. The Met wound up processing refunds that amounted to $2.3 million. Some reports suggest the total cost was even more given the overtime that went to those in the box office issuing refunds.

Eventually, the Met settled with its orchestra, adding to its ledger-book. Once again, Bing raised ticket prices. To the public, this all seemed like the company was claiming victimhood at the expense of the working musicians who were the ones actually suffering the loss of paid work. This reflected in the box office: While ticket sales had been at 96% capacity in a nearly-4,000–seat house in the previous season, they dropped to 89% in 1970. The company’s subscriber base, to this day, has not fully recovered, and it would take them another 10 years to make up for the $3.8 million loss they took on the cancellations. That’s to say nothing of the financial impact a five-month furlough had on 800 employees and the lasting ramifications this event had across the country for all organizations and artists.

Terry Riley in the 1970s (Source)

What had changed for the Met? How did it go from being an exclusive circle of elite subscribers (in the era of Gatti, it was able to cover its expenses on ticket sales alone) to begging for people to donate their ticket prices during an outage — and losing on the bet that they would? Consider the polished poise and restraint of 1960 in the pilot of Mad Men against the tone of its series finale, which is set in the autumn of 1970 against the Coca-Cola “Hilltop” ad. The decade had been defining for America with Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement, the Kennedy dynasty (and subsequent assassinations of both John and Bobby), The Beatles, the Manson Family, the Newport Folk Festival, and Woodstock (to name just a few), also impacted the world of quote-classical-unquote music — and the world beyond it.

The ‘60s revealed the holes in America’s system of equity and social support, which also meant that funding for the arts was being redistributed to more urgent areas of public life. The attitude towards this, as reflected in one fundraiser’s quote in Opera News, doesn’t exactly suggest that arts professionals were aware of the world beyond their halls: “You must remember that the Detroit Symphony competes with the Detroit ghetto for every donated dollar.”

Across the pond, Europe had rebuilt itself into prosperity after World War II, leaving musicians with more, and at times more exciting, options (as did the advent of commercial airline travel). The ‘60s also gave way to new musical centers around the country, more companies than had existed in the days of Caruso and Gatti, and a greater diversity within the genre of classical. Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and John Adams all began their careers in this decade. John Cage’s fame began to skyrocket and, following the 1952 premiere of 4’33”, he spent the ‘60s creating many of his most ambitious works. Terry Riley’s groundbreaking In C premiered in San Francisco in 1964. By 1971, Pierre Boulez would succeed Leonard Bernstein at the New York Philharmonic, continuing Lenny’s push to champion living composers with even more experimental series like the famous Rug Concerts.

In short, people in 1969 didn’t need the Met like they did in 1949.

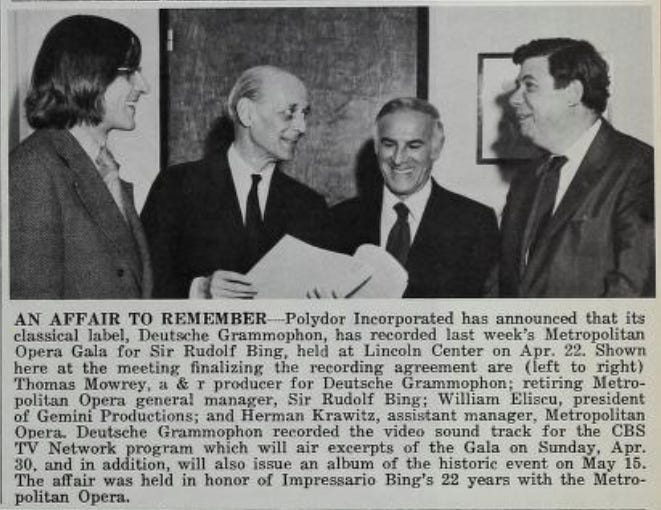

Not everyone at the Met was completely oblivious to the winds of change. One of them had been working closely with Bing, and (unlike Bliss) had the impresario’s trust and admiration, despite originally coming to the Met via Bliss. Herman Krawitz was a native of New York City and a graduate from City College. His experience on Broadway led Bliss to think he would be a good outside perspective to investigate a suspicious financial and working situation among the Met’s stagehands that had caused expenses to inflate. While he wasn’t steeped in opera the way Bing was, Krawitz thought it would be a good learning experience for the career he’d hoped to forge as a theater director.

The more Krawitz observed, the more he realized that the Met’s stagehands were powered by an intricate system of kickbacks and favoritism. This didn’t endear him to the stagehands who profited from this system, who organized a wildcat strike in 1953 when Krawitz came on board (a strike that was resolved in short order when Bing attempted to work the curtain for a dress rehearsal of Norma, and almost decapitated soprano Zinka Milanov in the process).

At this time, Bing didn’t care much for Krawitz, either. Although, to be fair, the only times he would see Krawitz were when he came in with another report that told him how poorly-managed his company was. But what Bing soon realized was that, for every problem, Krawitz came up with a suggested solution. Likewise, the Met’s stage crew began to see Krawitz as one of them: not an elite Mitteleuropan in the school of Bing, but the Bronx-born son of a Polish immigrant family who understood the way of their world. When the Met reopened after its 1969 labor dispute, Krawitz was there to personally greet every employee reentering the building for the first time in months, telling one dancer as he kissed her on the cheek, “I hope you dance as well as you negotiate.”

“His tone of camaraderie goes down well with all of the crafts, and relieved our stage situation of tension,” Bing would later write in his memoir, 5,000 Nights at the Opera. He also credited Krawitz with giving the best platform for works by everyone from Chagall to Zeffirelli. Bing brought Krawitz into management, and it was Krawitz who made sure the new Metropolitan Opera House offered as much of a better environment for those working behind the scenes as it did for those watching from the audience.

Krawitz was with the Met for over 15 years by the time they reached the disastrous season of 1969-70. In the beginning of 1970, the company’s shutdown and public financial issues made a number of candidates to take over Rudolf Bing’s position think twice. The company took out its first major ad in the Sunday edition of the New York Times that year, and its president, George S. Moore, told the paper, “We are not a Diamond Horseshoe anymore. We hope to widen our public.”

And that’s how the Met met Tommy.

Like most operas before it, “[m]yths have grown up around the recording of Tommy,” writes Pete Townshend in his 2012 autobiography, Who I Am. One of those myths was perpetuated, or at least reinforced, by Townshend himself, that he “started to write what eventually became Tommy out of pure desperation.” By 1967, Townshend’s band, The Who, were on their third year and third album. The early, lightning-in-a-bottle success of their song “My Generation” had defined a generation of rock, rebellion, and dissatisfaction (in one later recording, the track closes out with a cacophonous cover of Elgar’s “Land of Hope and Glory”). But, in a decade where every year was an era, 1967 looked a lot different than 1964.

The Who were trying to establish themselves artistically, a difficult task when you’re also dealing with sudden fame, negotiating the music business, and Keith Moon’s frequent drug-induced antics. Reading the works of Borges and spiritual leader Meher Baba (who would only communicate through written word and sign language), Townshend would then go onstage, look at the smashed equipment and tripped out audiences, and think two things:

This is now what The Who had hoped to become

The Who had no idea as to what they hoped to become

Sensing that his mission wasn’t “to embellish the acid trips of an audience that no longer cared when a song began or ended,” Townshend also grew wary of the music he did admire at that time — most notably The Beatles’s Sgt. Pepper and the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds. “These two great albums indicated the future, but passed on no tools, codes, or obvious processes that would lead to a door,” Townshend would later write. “I ached for more than just a signpost pointing to the future, which is what these albums were to me.”

Knowing that he didn’t want The Who to continue on as they had, and having seen the spiritual seeking that was pervasive in California — a search that echoed his own — Townshend wondered if he could give voice to these feelings in the form of a narrative paired with music. In the beginning of 1968, while on tour in California, he began to sketch out what would eventually become Tommy, a rock-opera that told the story of a young boy who, after witnessing unspeakable trauma, became (in order) a “deaf, dumb, and blind kid,” a pinball wizard, and a spiritual leader. The sensory deprivation that frames Tommy’s experience was, to Townshend, a metaphor for contemporary spiritual isolation.

“The boy is played by The Who,” he told Rolling Stone cofounder Jann Wenner and Boz Scaggs one night at the home of Jefferson Airplane’s Jack Casady. “He’s represented musically by a theme that we play… But what it’s really all about is the fact that the boy exists in a world of vibrations. This allows the listener to become profoundly aware of the boy and what he is all about, because he’s being created by the vibrations of The Who’s music as we play.”

Jann would later publish their conversation in Rolling Stone, and the magazine announced Tommy in August of 1968.

“Actually, Pete has been writing these operas for some time, and a lot of our hits come from them” bandmate Roger Daltrey told Rolling Stone. “‘I’m a Boy’ was from an opera he wrote about living in the year 2000 when there is a machine that helps you select the sex of your baby. That song was about a woman who couldn’t believe that the machine had made a mistake and she’d gotten a boy instead of a girl.”

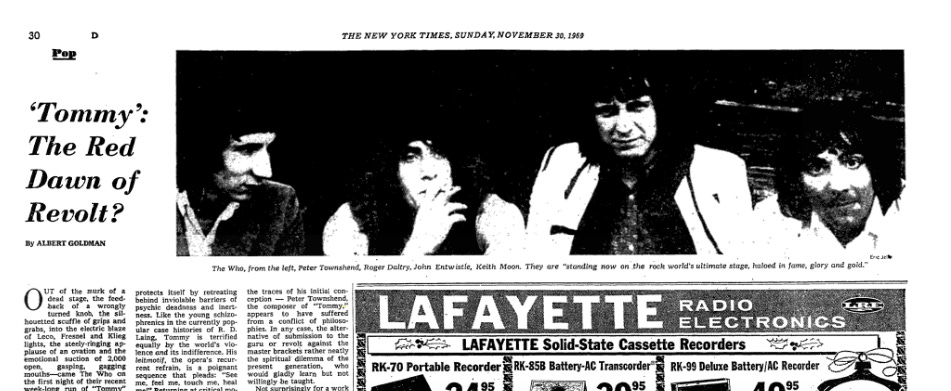

“It’s a Boy” would factor into Tommy, which the band debuted in 1969, including a recording released in May of that year. Reviewing for The New York Times, Nik Cohn called the storyline of the work “unimpressive.” But this didn’t remove it from the other operatic canon. And, as an album, Cohn declared Tommy “just possibly the most important work that anyone has yet done in rock.” Beyond the standalone merit of tracks like “Pinball Wizard” and “We’re Not Gonna Take It,” Tommy made up for a whole greater than the sum of its parts. When The Who brought Tommy to New York in November of that year, playing at the Lower East Side institution Fillmore East, Albert Goldman compared it to the furor of Beethoven’s “Eroica,” likened its ending to “the unbroken finales of Mozart operas,” and saw the revolutionary and mystic echoes of Wagner’s Ring Cycle in Townshend’s overall approach.

And, because it was November of 1969, Goldman had the opportunity for a prophetic kicker:

“No one has suggested yet that the opera be mounted as an opera at the darkened Metropolitan, but the idea merits serious consideration. Even apart from the heady symbolism of such a change of guards, the avant for the derriere, think of the fabulous social opportunities such an event would afford. Can you imagine the lords and ladies of the hip establishment turning out on opening night in their frumpy finery? Flaunting their mangy furs and pasty jewels? Removing the world’s longest coats from the world’s shortest skirts in gravely pornographic ceremony? Raising lorgnettes with dark lenses? Rolling the programs into giant joints? (SPecial programs with each page a different color and the last page soaked in acid so the whole audience could come together, as the ‘I Ching’ enjoins, during the finale.)”

(The entire review is a small masterpiece, but I’ll also keep include one more quote from Goldman’s conclusion: “After all, Verdi’s ‘Ernani’ sparked a revolution in Italy — why shouldn’t ‘Tommy’ trigger the first gun of the American revolution from that citadel of uptightness, the Met?”)

Also in the audience at the Fillmore that evening was Leonard Bernstein, who went up to Townshend afterwards, grabbed him by the shoulders, stared into his eyes, and asked if he “understood the importance of what [he’d] achieved.”

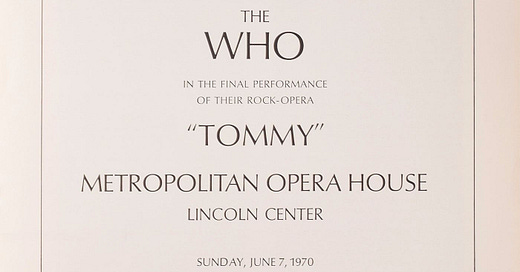

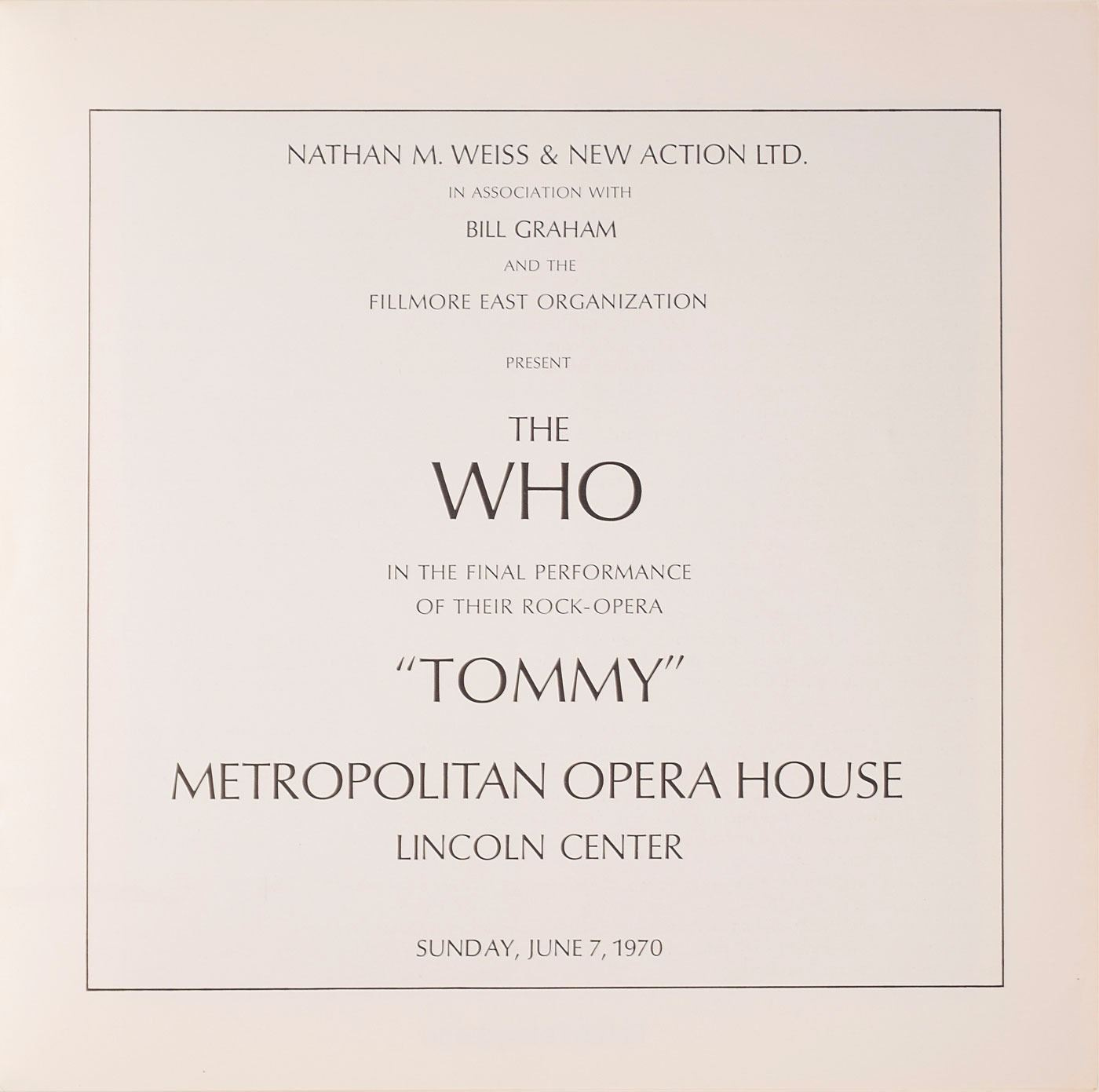

Less than six months later, on May 16, 1970, the Times announced that the Met would present Tommy.

Whether or not Goldman’s review served as any impetus for the Met’s first foray into rock is unclear. And whether it was The Who that approached the Met or vice versa is equally debatable. Townshend’s autobiography says it was concert promoter and Fillmore impresario Bill Graham who brokered the deal (although his book also mentions that the deal came together in June of that year). A Rolling Stone review credits it to promoter Nat Weiss. The Times, meanwhile, places the responsibility on Krawtiz’s shoulders.

Given that Krawitz was a leader in bringing the Met into conversation with its neighbors at Lincoln Center and familiar with the New York that existed beyond the opera house, it’s hard to believe he wasn’t at least integral to the performances. If nothing else, we can rule out that this was the brainchild of Bing (although according to one report he listened to the LP and enjoyed it, he doesn’t mention the show in either of his memoirs).

If nothing else, Krawitz was the public face of the Met’s alignment with The Who, the one willing to go on the record in the Times as arguing against the show being “lowbrow fare for the highbrow house” (along with the suggestion that The Who should become The Whom for the evening).

“All productions of quality come to the Met,” Krawitz told The Times.

Of all people, The Who seemed to be the ones most skeptical of the engagement. While Townshend initially called the gig “dire,” he would later soften his opinion, saying “I was proud to be there and confident we belonged,” but that the shows themselves “weren’t much to my taste.” The concept of an album-length work may have provided more sustenance than a three-minute pop song, but what Townshend, Daltrey, Moon, and John Entwistle would discover was what the Met Orchestra already knew: Performing that kind of a work (in The Who’s case, twice in one night) was exhausting and time-intensive.

After the second set, the end of which the band pushed through “like marathon runners crossing the finish line,” the crowd cheered for 15 minutes, anticipating an encore. When Bill Graham refused to send them home, Townshend did it himself. “Boo!” one audience member shouted.

“After two fucking hours, boo to you, too,” Townshend answered, flipping his mic stand into the empty orchestra pit.

The Met’s ushers weren’t sure what to do with the ensuing reaction from the crowd (according to some reports they also had to brace themselves for the contact high they were getting from the Met’s new audience), but fortunately both Graham and Weiss were on-hand for that very reason, along with ushers from the Fillmore East.

Yet, despite the critical and financial success of the evening — having made $2 million in record sales as of its Met debut, Tommy played to sold-out audiences in both shows — Tommy didn’t seem to act as the great bridge to a wider public that Moore had hoped for. An 18-year-old audience member, Henry Crawford, told the Times: “This is playing footsie. The rock culture will only be pure after we get rid of all the other trash that goes on here. By coming here, we’re supporting capitalism… This is an establishment takeover.”

Rolling Stone also wasn’t impressed by what it considered to be a gimmick. “Outside, the ballet customers at the New York State Theater kept ignoring the curtain bell to jam the second-floor terrace so they could watch all the hippies parading across the Lincoln Center plaza beneath them,” wrote Alfred G. Aronowitz. “Beneath them? Of course, beneath them.”

To cover Tommy, the Times had sent both classical critic Donal Henahan and religion reporter McCandlish Phillips (whom, parenthetically, would be dubbed “the most original stylist I’d ever edited” by former managing Times editor Arthur Gelb, the father of current Met general manager Peter Gelb). It was Phillips who captured the spirit of the evening, including the cynical teenagers in the audience — who, to their credit, were described by Met ushers as “much more polite than their parents.”

Henahan, meanwhile, was less sold on Tommy as an opera, despite Goldman’s connections to Verdi, Wagner, Mozart, and Beethoven in November of ‘69. “The hour-long piece… could hardly qualify as opera under any except the most propagandistic definition,” Henahan wrote in the opening of his review, while later admitting that the work “proved a lot of innocent fun.”

And, just like that, it seemed like the doors of the Met would shut once again towards a wider public. While the shows seemed to be a success, they weren’t regarded as a Met production (no record of The Who exists in the Met Opera’s Archives, which do note a concert that they performed with Ella Fitzgerald). Perhaps, too, it seemed unlikely that they were going to win over a younger audience with rock operas; dressing up rock stars with Swarovski chandeliers coming off as the equivalent of Steve Buscemi pretending to be a teenager.

The managerial changes at the Met didn’t help matters either. Following Bing’s retirement in 1972, the company hired Swedish opera manager Göran Gentele as the new general manager. Gentele died in a car accident before beginning his tenure, and so the Met quickly pivoted to Lincoln Center’s Schuyler Chapin. Krawitz, who had been considered a natural replacement for Bing, left the company shortly after, a decision Fiedler suggests was the wrong one for the Met as Chapin’s era would make clear. Krawitz, meanwhile, joined the American Ballet Theatre as executive director in 1977, in that time hiring Mikhail Baryshnikov as the company’s artistic director. But in 1983, he abruptly stepped down following a nine-week strike and resulting financial crisis.

The Who initially claimed that the Met performances of Tommy would be their last, a decision that Henahan supported.

“The best rock depends on the surge of the moment; when it takes itself too seriously it dies,” he wrote, adding, “What could be less exciting than petrified rock?” But then Ken Russell made a trippy film version of the work in 1975, which included The Who performing alongside Ann-Margret, Oliver Reed, Elton John, Eric Clapton, Jack Nicholson, and Tina Turner. It’s a work that has continued performances, including a 1993 Broadway run overseen by Townshend and directed by Des McAnuff (who helmed a 2011 production of Gounod’s Faust at the Met). The Who even returned to the Met in 2017 for a performance of their later work, Quadrophenia.

In the end, Townshend never met Meher Baba, a fact he sorely regretted. The guru died on January 31, 1969, during the period that the band was recording Tommy. But Townshend would pay homage to his fellow spiritual seeker with another song, 1971's "Baba O'Riley.” He wrote the song as an homage to two of his greatest mentors. One, of course, was Meher Baba.

The other was Terry Riley.

Thanks for subscribing to Undone. Next week: announcing a new mini-series.

Further Reading

Who I Am by Pete Townshend (2012)

The Who Concert File by Joe McMichael and Jack Lyons (2004)

Molto Agitato: The Mayhem Behind the Music at the Metropolitan Opera by Johanna Fiedler (2001)

TOMMY: The Musical by Pete Townshend, et. al. (1993)

The Met by Martin Mayer (1983)

A Knight at the Opera by Rudolf Bing (1981)

5,000 Nights at the Opera by Rudolf Bing (1972)

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts by Ralph Martin (1971)

“A Matter of National Concern” in Opera News (1970)