Hi there. I’d planned on taking this week off as I work on the next few installments of Undone. Then Tuesday happened. Below is a piece I had written last year (2019) to coincide with both the Met’s exhibit “The World Between Empires” and a new album released by Kinan Azmeh. The piece never went to print, but I had saved the draft and have been thinking about it a lot in the last few days. For the first time, and with slight edits, here it is.

At what point do our narratives become our identity? And what determines which of our manifold narratives becomes the one to which we pin that identity?

I’ve spent the better part of the last decade obsessed with these questions. I asked them in 2011 while watching my ancestral home of Syria erupt from Arab Spring to civil war. I asked them again when the United States stopped brushing its white nationalism under the rug. I’ve been asking them again this week in the aftermath of Beirut, as Twitter punditry became dominated by armchair political scientists and policy analysts.

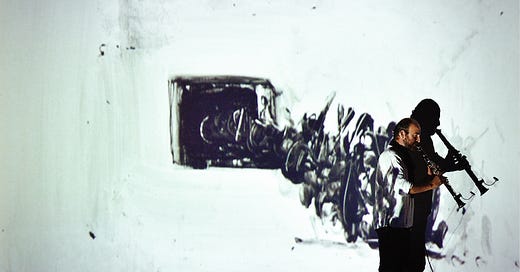

Kinan Azmeh, with artwork by Kevork Mourad, in Home Within. (Photo: Kinan Azmeh)

“If you want to know the Syrian story, you have to listen to 24 million Syrian stories. You have to listen to every Syrian person’s story,” clarinetist and composer Kinan Azmeh told me in an interview a few years ago. “There’s no pure ‘culture.’ Something that is now Syrian might have been something else before, and it might become something else later. Cultures are dynamic.”

While the Metropolitan Museum of Art, like many museums, contends with narrative and ownership, they’ve also in recent years taken steps to explore the same dynamism that Azmeh mentioned. In response to the white supremacist appropriation of Greek and Roman sculpture, the Met went on the record in everything from the New Yorker to Full Frontal with Samantha Bee to help dispel the myth that classical statues were exclusively white.

That work continued last year with the exhibition “The World Between Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East.” It featured a collection of nearly 200 objects encompassing a time period between 100 BC and 250 AD, and an area between Imperial Rome and the Iranian empire of Parthia. (That map has since been redrawn; Romans and Parthians are now Yemeni, Iraqi, Jordanian, Israeli, Palestinian, Lebanese, and, yes, Syrian.)

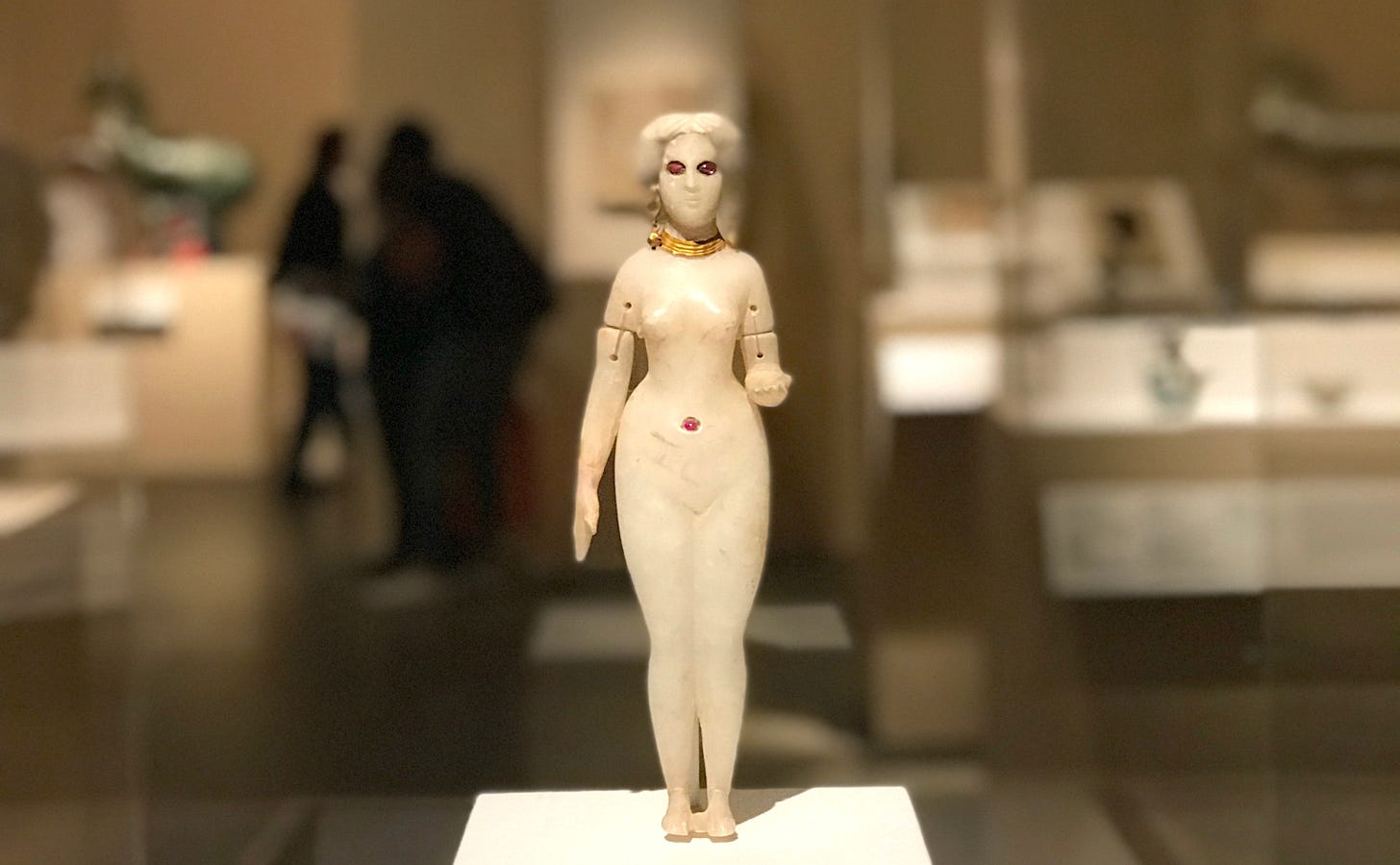

Statuette of alabaster goddess, from Babylon, with movable arms and ruby eyes & navel (Photo: Olivia Giovetti)

I’ve written elsewhere about the overlap of culture, conquest, and narrative that covered the Mediterranean region. In a similar vein, Met curator Michael Seymour stressed that “The World Between Empires” was not about the empires, but rather about the people who lived within them and who forged “a complicated patchwork” of identity amid the overlap of dominions. Pieces like an alabaster statuette of a nude goddess (eyes and navel gleaming with ruby inlay), are object lessons in these overlaps and their complexities. Is the goddess Aphrodite? Venus? Ishtar? It’s a question of divine identity that doesn’t necessarily need an answer (especially in 2020).

Such a focus on the personal over the political is something that Azmeh has also been pushing for as a musician. “I always find it interesting when people talk about Syrian music today, it’s usually in connection with the refugee crisis,” he says. “I have the feeling it’s important to change the discourse a little bit, to where people talk about culture regardless of political consideration.”

Azmeh was born in Damascus, just a few years after the beginning of Hafez al-Assad’s term in office (which would last for nearly 30 years). The subsequent reign Hafez’s son, Bashar, coincided with — indeed, prompted the Arab Spring movement in 2011 when a group of teenagers in Daraa were arrested for anti-government graffiti. The violence escalated and by May of the same year the first Syrian refugee camps opened in Turkey. According to the International Rescue Committee, in 2017 nearly 10,000 Syrians a day fled their homes. A 2018 poll commissioned by the IRC suggested that only 100 Syrians would be resettled to the US (compared to 6,500 in 2017).

That’s one narrative.

While the Syrian civil war has resulted in thousands of Syrian artists displaced across the world, artists who are categorized, for political purposes, as refugees, Azmeh argues that “the music-making is not, should not, be narrowed down to such.… This culture should be celebrated regardless of the political representation of it today.”

Azmeh compares the Sisyphian task of defining Syrian music to the similar zero-sum game of defining American music. Is it the music that is played in the country? Music written exclusively by composers who were born in that country? What if a non-Syrian composer borrows elements of Syrian music?

“The celebration of Syrian culture is coming through this very narrow window of, ‘Let’s see what these refugees brought’ versus ‘This is an ancient history,’” he says. “This for me has been a very important topic to bring out. A crisis should not be our main motivator to be curious about a culture.”

The World Between Empires at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019 (Photo: Olivia Giovetti)

As the Met Museum exhibit suggested, the cultural overlaps over millennia of occupation and trade routes means that we lose the sense of a true “beginning.” Or, perhaps more accurately, they suggest that there are always new beginnings; a cultural ouroboros devouring its own tail, beginning again.

Beyond understanding the beginning, we also struggle to understand the present. As anthropologist Jonathan Holt Shannon wrote in Among the Jasmine Trees, “the modalities of performing and enjoying music in Syria, diverse and contested as they are, reveal some of the nodes of solidarity and fractures in a society coming to terms with itself and its place in the modern world.”

The present moment in Syrian music (the modalities of performance and enjoyment) speaks to the larger diversity and multiculturalism (and disparities and inequities) within the SWANA region. Styles span Arabic hip-hop to “Western”-style classical music based on Syriac traditions (which had influenced the same “Western” style we know today). The content has become broader, as well, with taboo subjects like politics being used as narrative devices. As with any uprising, music as a form of protest is a given, and especially so for a culture rooted in music as social life.

“I’ve always been exposed to two schools of thought about the arts and art-making,” Azmeh said when I asked him about the idea of making music as a Syrian after 2011. “One of them suggests that it’s the artist’s role to mirror the world, to document the world. And the other school of thought I was also exposed to is that the artist’s role is to recreate a world that would be perfect according to him or her; to create something that is independent from the world outside.”

When Syria began to spiral from Arab Spring to civil war, Azmeh’s emotional landscape shifted. The need for art disappeared, and he was in search of something more immediate. It wasn’t until the first anniversary of the revolts in Daraa that Azmeh felt as though there was something left to be expressed through art. “Had I been able to explain why I did it, I would not have done it, I would just say it,” he says of the specific impulse to create what would eventually become the multimedia project Home Within, developed with Syrian-Armenian artist Kevork Mourad.

Home also factors into Azmeh’s 2017 work The Fence, the Rooftop, and the Distant Sea (a work he premiered with Yo-Yo Ma and the Elbe Philharmonie just before the first Muslim-majority travel ban went into effect). A duet for Azmeh and Ma, the impulse for the work initially came when Azmeh was sitting on a rooftop in Beirut, staring past a fence at the vast expanse of the Mediterranean. In that moment, he thought of his parents, still in Damascus. He thought of home.

Released last year as part of the album Uneven Sky, The Fence, the Rooftop, and the Distant Sea gives its soloists room for discourse. Calvino-like, they grapple with the idea of home: When do you have it? When do you lose it? How do you find it again? What begins as a fraught series of questions soon resolves into a lullaby, an innate sense of “home” regardless of geography. Home is, as Azmeh has suggested before, within.

Thanks for subscribing to Undone. See you next week.