Four years ago, I wrote a piece for VAN on musicians who were following the deceptive cadence of the US election in the days between Election Day and when the vote was finally called. It was a balm to spend the first 36 hours after that Tuesday having so many conversations that touched on a range of emotions and reactions, with people like David Harrington, Reginald Mobley, and Raquel Acevedo Klein. Everyone I spoke with was aligned politically in the broad sense, but since there’s no such thing as a monolith, there were as many threads to tug on as people after the initial response of nervous laughing and guttural sighs. In this sense, the experience reinforced one of Harrington’s observations, made in reference to Pete Seeger (whose music the Kronos Quartet had recorded in anticipation of this same election): “When I think about his life’s work and the way he brought his audience into making a community, to me that likely is part of the answer now.”

That notion of community resonated in its own way through many of the interviews, as did the question of “Whose community?” Mobley had told me that 2020 was a mixed bag for “so many people,” but that was an experience that had gone on “even longer for people who look like me and feel like me.” Klein, whose family is largely Puerto Rican, recalled 2017’s Hurricane Maria and the feeling of being left out of the American equation, grappling with feelings of both loss and a sense of “attack from our country, our government.”1

I noticed that VAN published a similar piece last week, with musicians responding to the quickly-called election in favor of Trump. “All this week, we’ve been fielding responses from musicians in America, asking for their immediate reaction,” the introduction reads. “Here is a selection of them.” Statements follow from cellist Seth Parker Woods, conductor Alan Pierson, composers Christopher Cerrone and Judd Greenstein, baritone Davóne Tines, and pianist Jeremy Denk. The article also includes an entry from violist David Aaron Carpenter that had been made to social media, apparently now deleted, that featured “Carpenter and his family with a MAGA-hatted Donald Trump, with the caption, ‘Ready for the Golden Era of America and a more peaceful world.’”

I know that VAN had reached out to some female musicians for this piece as well, and that no one likes to be reduced to one singular identifying feature (multitudes and all that). However, I remain flummoxed by the fact that every response published by VAN came from a man. I also realize that, by being a woman who once worked for VAN and pointing this out, I’m most likely going to come off as one of so many Alex Forrests still running around, boiling rabbits and listening to Madama Butterfly. Still, the optics of having the election reflected back to me in this way (even by musicians I know and admire) felt like an entry in the “All Male Panels” Tumblr.

Between 2012 and 2017, I worked in digital marketing for both individual artists and institutions in classical music. Social media had become a revolutionary tool for artists, many of whom had, until then, only seemed knowable from New York Times profiles or Deutsche Grammophon album covers. In the early years, many musicians who now share every facet of their life on Instagram were anxious about posting any form of personal content online. Politics was the one area that was categorically off-limits for most artists. When they did post photos with politicians, it was more of a statement of status than of ideology. Most of the musicians you could count on to offer a steady stream of commentary on either America’s or the world’s body politic fit a specific mold: Younger, independent artists whose work was grounded in politics. They were often composers, often white, and often male. This vibe was so dominant that I remember one composer suggesting that someone set the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings of former US Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, not realizing that composer Melissa Dunphy had already done so — and had been featured on the Rachel Maddow Show for it.

Much has changed since then. The 2016 election served as a springboard for many artists to leverage their platforms towards various pressing issues, the politics of which could no longer be ignored. Musicians have always been political, but this was a new level of visibility that came at a critical point globally — underscored but not wholly defined by Trump’s win. This momentum has kept up against a laundry list of crises in the last eight years, and while for many organizations and individuals it can be stop-and-go (two words: black squares), there are many artists whose inherent sense of activism is a constant in their work. There are also those like Carpenter who seem indifferent towards activism but will take advantage of a news hook to promote themselves.2

Like Carpenter, many were also posting in the immediate aftermath of the election even if they weren’t giving exclusive commentary. Joyce DiDonato (whom I followed to a refugee camp in Athens last year and who has been involved in prison reform since she first performed in Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking) made a raw and elegiac post to Instagram the day after the election, describing a play-by-play of her emotions between Tuesday night and Wednesday evening, from feeling “as if projected unwillingly onto an old movie screen: out of body/out of heart” to “the inevitable atomic, blink-of-an-eye tsunami that will conjure storms and waves and troubles.”

“The first thought I had was ‘I guess sexism runs deep in the US’ and then caught myself. That’s what all the voices I’ve been listening to have prepared me to think — and it’s just kept me in a vacuum,” mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke wrote earlier this week on Instagram, wrestling in real-time with the various identity politics and other issues at play in this vote.

Gender wasn’t everything, but it also wasn’t nothing. Presciently, one day before the election, the New York Times reported that the New York Philharmonic had dismissed principal oboist Liang Wang and associate principal trumpet Matthew Muckey. This came after earlier allegations of misconduct against both musicians that resulted in a saga of previous dismissals, arbitrations, additional allegations, and an eventual re-dismissal. A Vulture report from earlier this year prompted the reinvestigation — score one for freedom of the press — and quoted one male Philharmonic colleague saying in a police report that Liang and Muckey “think everything in the world is theirs for the taking.” I’ve thought a lot about that line in the last week, amid the proliferation of young men telling women online, “Your body, my choice.”

While Philharmonic president Deborah Borda told the New York Times “We have done the right thing and we have followed the letter of the law,” Wang and Muckey plan to continue fighting what they consider to be an unfair dismissal. Yet I have to wonder what good the letter of the law is in a country whose legal system has been both openly defied by and indefinitely shaped by Trump. I also wonder how much good faith will be afforded to survivors of sexual harassment and assault (especially in the relatively unimportant world of classical music) in a country where people willingly elected a legally-codified sexual predator.

“It's a particularly vicious slap in the face to those of us who’ve fought to create safer work environments for women and gender-marginalized musicians,” composer Tina Tallon tells me via email. “It’s all but guaranteed that policies designed to allow us to focus on our work free from the threat of sexual harassment and violence will be rolled back. Support systems and modes of recourse for those who do unfortunately experience these things will be eroded, and the promised dissolution of the Department of Education leaves Title IX protections (as broken as they may be) in question.”

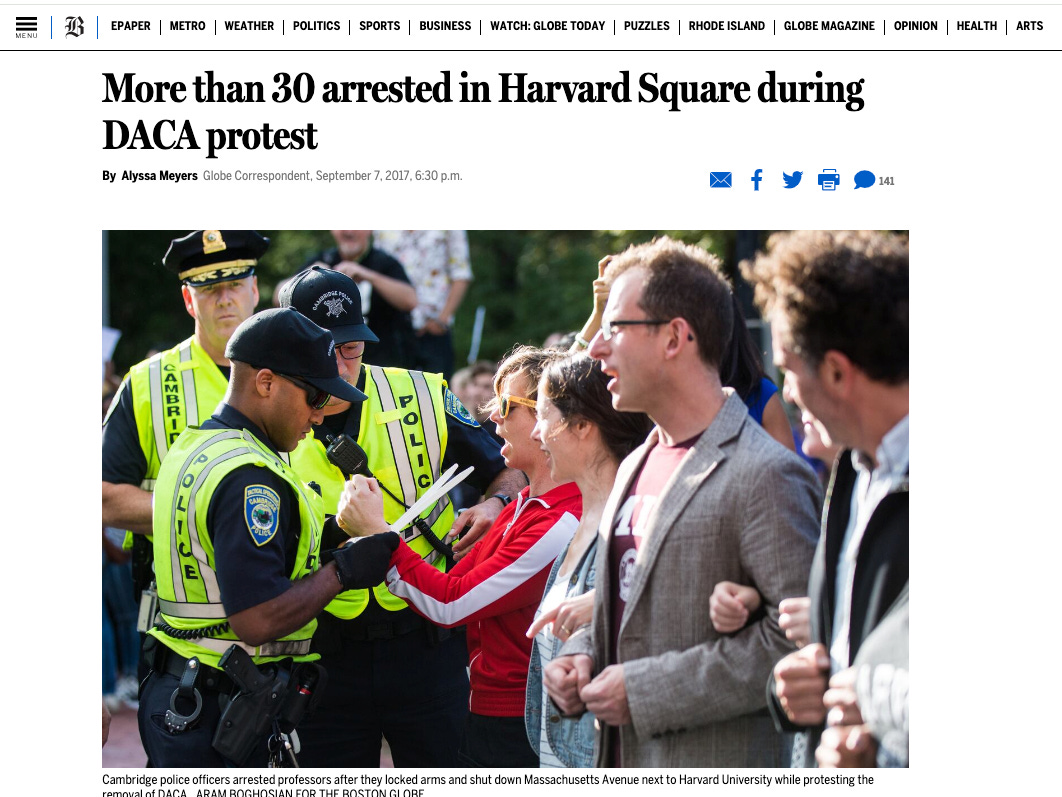

The calamities of Trump’s first term were felt explicitly throughout the classical music world. In September 2017, amid the rollback of DACA, flutist and newly-minted Harvard faculty member Claire Chase was pictured in the Boston Globe, her hands getting zip-tied by Cambridge Police, as they responded to a faculty demonstration in support of the protective measures for young immigrants. “It’s not business as usual because the Trump administration is targeting our students,” another Harvard professor said shortly before she was also arrested. The future looks even bleaker for both immigrants and protesters in this new term.

Within the first week of his administration, musicians were left in impossible situations. The so-called Muslim travel ban left Syrian clarinetist and Silkroad Ensemble member Kinan Azmeh temporarily uncertain as to whether or not he would be able to return to his home of 16 years in New York, even with a green card (he was in Beirut when he learned of the executive order). It wasn’t necessarily a new experience of anti-Arab racism for Azmeh, but it was an escalation, and one that set a dangerous precedent: “What does this mean, long-term? What does this mean for everybody in the world who is discriminated against, just because they have a different skin color, a different passport, different religious beliefs?” he asked Rolling Stone in February, 2017. Fellow Silkroad member and Iranian kamancheh player Kayhan Kalhor faced similar uncertainties that NPR’s Anastasia Tsioulcas details in this piece from 2021.

All of this bodes to get worse as Trump inherits a global situation far more fraught than it was in 2016. “This has been the most devastating political outcome in my lifetime, although it’s coming very close to what we’ve experienced in Israel,” cellist Maya Beiser tells me. “In particular for me, coming from Israel originally and seeing what’s happened there with the radical right taking over the country and basically eviscerating everything, I am keenly aware of the devastating effect that the next four years of a Trump administration will have on this country, on the world, and on humanity at large.”

Yet, as Reginald Mobley hinted at in 2024, there is a “business as usual” at work within the administration, because it capitalizes on sentiments that existed independently of his influence. The day after the election, Silkroad’s current artistic director Rhiannon Giddens shared a video where she played the song “Pompey Ran Away” on her banjo, with the caption: “An opportunity to lean into art music and beauty as those of us who weren’t surprised the nation showed itself nevertheless need the moment to feel sad.” Giddens, like Joyce DiDonato, looked somewhere between being projected unwillingly onto an old movie screen, and caught in the inevitable atomic tsunami.

Also the day after this last election, pianist Lara Downes posted an excerpt from Langston Hughes’s “Let America Be America Again” to her Instagram that rendered Giddens’s note about the nation showing itself even more explicit:

“Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.

(America never was America to me.)

Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed—

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.

(It never was America to me.)”

Downes dedicated her most recent album to understanding American identity in its plurality, a sense that Hughes captures from a different angle in this poem. His narrator is “the poor white, fooled and pushed apart.” He is the descendant of enslaved people. He is an indigenous American “driven from the land.” He is an immigrant “clutching the hope I seek— /And finding only the same stupid plan./Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.”

Maybe, I think as I continue to pore over social media reactions for a more diverse array of classical voices on this election, this is why many of the musicians I expected to be commenting more readily in the last week were tacit. While Trump will inarguably be materially worse for America (and the world) than Harris, Harris winning would not have been a wholesale victory. “When I think of America, I think of master narratives that are used to win elections; I don’t think of many good things,” Vijay Iyer told me in an interview last year.

Vocalist Katherine Goforth echoed this sentiment in a post from last week that also reflected on the history of trans suppression in the ’20s and ’30s: “It’s infuriating to read these [history] books and see women who were born into the same ignorant and disinterested cultural context I was, the same unsupportive families, the same religion teaching the same self-hatred. Why did I have to struggle the same way that they did to come to know myself? It’s not because the information wasn’t there, but because it’s kept from us, generational erasure.”

(Above: Another reaction to the election, shared by Laurie Anderson.)

“My opinion is that men never have stopped being scared or feeling emboldened to harass, assault, and abuse women,” says mezzo-soprano Nikola Printz. “Look at the kind of men we continue to uphold in our industry; I still see pictures of my colleagues with James Levine and Plácido Domingo!… I think what is changing is that more women are buying guns.”

Printz also points out that, in their state of California, there was more on the line than the federal elections. Several propositions failed to pass in the state, including those that would have made it easier for governments to fund public housing, banned involuntary servitude as a form of criminal punishment, and enabled local governments to impose rent control. One resolution that did pass will reclassify some misdemeanor theft and drug crimes as felonies. Taken together, these measures will have an undue impact on low-income (and largely non-white Californians) struggling to live in one of the most expensive states in the country.

“Do you think the average opera-goer gives a shit about people in the prison industrial complex?” Printz asks. “We couldn’t even get opera companies to save an innocent man on death row, and yet I’m doing Dead Man Walking next year? It’s maddening how we cherry-pick what we give a shit about in classical music. It drives me bonkers that we show stories with these grand themes of humanity, but we tangibly cannot connect to people on our planet experiencing those things.”

Ultimately, that seems to be the more defining reaction to this (and any) political moment: The way that artists force us to confront what we give a shit about. To, as David Harrington said of Pete Seeger, bring audiences into making a community.

Another moment from the first Trump administration I was reminded of this year came from September 2018, during the Resonant Bodies Festival. Part of Helga Davis’s set had her “The Star-Spangled Banner,” deconstructing the work and giving special attention to the word “bombs,” turning it over and over in her mouth and ultimately singing it to the tune of the Queen of the Night’s vengeance aria from The Magic Flute. Davis happened to sing it on the 17th anniversary of September 11. The layers of meaning tied up in that performance were at once liberating and suffocating.

Another take on “The Star-Spangled Banner” via composer Allison Loggins-Hull.

The same festival (which also overlapped with a local election in New York) featured Gelsey Bell singing a song titled “This Is Not a Land of Kings.” Fiddling with the zipper of her dress during an onstage costume change shortly afterwards, Bell joked: “This dress is part of my legacy as a woman,” adding, pointedly: “I hope you all voted today.”

Puerto Ricans, while US citizens, cannot vote for the president if they don’t live in one of the 50 states or District of Columbia

I still have photos with a former client and Trump; photos he later posted after Trump won the 2016 election. He soon deleted them, baffled by the outpouring of negative feedback.