This is the second part of a two-part essay. Read the first half here.

It was Aristotle Onassis who originally suggested to Maria Callas that she try her hand at film.

Having been credited with redefining the way operas were performed — creating a demand across houses not just for singers, but singers who could act — Maria seemed like a natural fit for the big screen. There had been offers, including the female lead opposite Gregory Peck in the wartime epic The Guns of Navarone (the part went to Irene Papas) and a Tennessee Williams adaptation, Boom!, that eventually starred Elizabeth Taylor (she may have been wise to turn down this one — reviewing Boom! for Newsweek, Paul D. Zimmerman called it “a pompous, pointless nightmare”).

Pasolini’s Teorema

While she was initially reticent, by 1968, single and unable to sing like she did in her earlier years, Maria was ready to reconsider her options. At the peak of this personal and professional crisis, producer Franco Rossellini stepped in. He offered Maria the chance to play Medea in a non-musical film adaptation that Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini had been mulling over. Intrigued, Maria watched the director’s newest release, Teorema, in which actor Terrence Stamp visits a rich family’s villa in Milan, and seduces each member of the family.

Maria walked out of the screening halfway through.

“The man is mad!” she shouted during a late-night phone call to her friend, the journalist Jacques Bourgeois. “A young man goes to spend the weekend with a family in the country. He makes love to the mother, then he makes love to the daughter, and then me makes love to the son!”

Bourgeois paused. He had been woken up by the phone and was still getting his bearings as he processed Callas’s tirade. He finally replied, “That’s God.”

“What do you mean, God?”

“Maria, the young man in the story represents God. It is to be taken symbolically.”

Now it was La Divina’s turn to pause. “God? But that is blasphemous!”

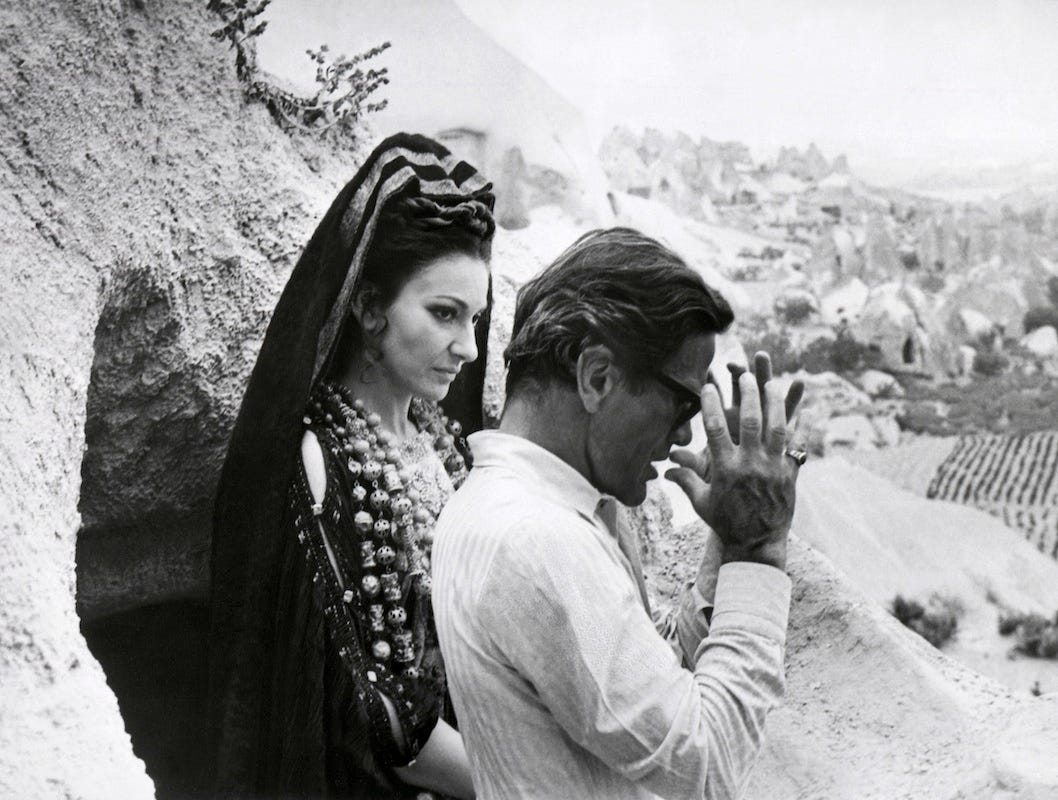

Callas and Pasolini on the set of Medea

Nevertheless, Maria was intrigued. She consulted her astrologer in Paris, a move that appealed to Pasolini who could be described as spiritual-but-not-religious. She must have also been taken by the fact that Pasolini wasn’t a fan of opera. In fact, it had only been her frequent recording companion, tenor Giuseppe Di Stefano, who made the Italian director consider opera as a serious art form. Even after he came around to the medium, Pasolini still felt all of the swooning over Maria’s performance as Tosca was blatantly queeny. (This probably also appealed to Callas, who famously loathed Tosca compared to the bel canto repertoire like Medea, despite being better-known today for her recordings of the former.)

While Onassis, also not a great opera-goer, seemed to prize Maria beyond her voice, he still saw her as Callas, a highly-prized object to be owned. In his defense, Maria enjoyed being owned. When director Franco Zeffirelli asked her why, after taking up with Onassis, she had also given up singing, she responded, “I have been trying to fulfill my life as a woman.”

For a child of a dysfunctional family who never seemed to have stability, Onassis’s wealth combined with his apathy towards Maria continuing to have a career must have seemed like a solution versus another problem. The trouble with such logic was that what Maria really wanted was someone to accept her, fully, for who she was, for someone to love the Maria that was often overshadowed by Callas.

Pasolini may have been one of the first men in Maria’s professional life (and possibly even personal life) to want her for herself — not as Callas the voice, Callas the diva, or Callas the icon, but as Maria.

On October 19, 1968, Maria Callas agreed to star in Pasolini’s Medea. On October 20, Onassis married Jacqueline Kennedy on his private island of Skorpios.

Pasolini’s Medea wasn’t bel canto. Nor was it lush Puccinian melodrama. Having once described cinema as “the written language of reality,” the director (who was both openly Marxist and homosexual, in a time when both identities were considered taboo), favored a blunt style of directing that looped around back into abstract. While still heavily symbolic, Teorema was one of his glossiest productions up to that point with a real budget and actors. Normally, he favored using non-professional actors who embodied the roles he was casting, versus performers who could pretend for the length of the shoot. It’s why he wanted Callas.

“Here is a woman, in one sense the most modern of women,” he said of his star. “But there lives in her an ancient woman — strange, mysterious, magical, with terrible inner conflicts.”

The shoot took place the summer of 1969, stretching across Turkey, Syria, and Italy. Pasolini saw Pisa, a stand-in for Corinth, as a crucial choice that stood for his take on the ancient myth: As the home of Galileo, Pisa symbolized logic and reason. It was the birthplace of rational thought in the face of ancient religion. Indeed, Pasolini’s Medea has very little to do with the central love triangle between Medea, Jason and Glauce. Nor does it focus on Jason’s quest for the Golden Fleece, or dwell too much on the act of infanticide. Instead, the central conflict is between tradition and modernity; between primal sensuality and civilized rationalism.

We first see Medea in full high-priestess mode in a scene depicting a ritual sacrifice of a young man to Medea’s grandfather, the sun god Helios. She stands with other monarchs of Colchis as the man is led in procession to the open field. He pauses to look at her, and smiles like an ecstatic fan at the La Scala stage door. His death is quick, his blood is smeared on the fields to keep the land fertile, and then the people of Colchis celebrate. “Give life to the seed, and be reborn with the seed,” Medea says, a premonition of lines that would later show up in the final scenes of Midsommar.

Pasolini turns this celebration into a feast of fools, inverting the power dynamics in a scene of orderly chaos. Medea’s brother is dragged down a hillside by children, who beat him with branches and sticks. Still under the burden of her heavy dark robes and layers of jewelry, Medea is tied to the same gibbet that held the young offering and spat on by her people. But there’s no resistance from Medea, only the cosmic balancing of the books. Critic Stephen Snyder describes this world as one without people as self-sufficient agents, but as inherited roles in an inherited structure. “Everyone is, in a sense, the sacrificial victim to the rite of spring.”

It’s barbaric (a word that’s often used to describe Medea in the original Euripides text), but it’s also a birthright. And Colchis, which in real-life was the mythical, mystical landscape of Cappadocia, is vibrant for it. When Jason and the Argonauts enter the kingdom, they come in not as liberators, but practically as colonizers. Something inside Medea snaps when she first sees Jason, and the reaction in Callas’s eyes makes that electricity palpable from the screen.

You can understand the impulses and synapses firing that lead Medea to abandon everything she’s ever known, to kill her brother, and steal the Golden Fleece from her temple (a spoil of war for Jason) in order to run off with this stranger. It’s as if a prophecy comes to life. Whatever dreams of grandeur and greatness Medea had suppressed in order to be part of the society of Colchis are unleashed by Jason.

But that energy loses its initial charge. When Medea abandons Colchis for Corinth, so too does Pasolini abandon the sun-baked Anatolian desert for stone-faced, claustrophobic rooms that seem more like prisons than palaces. She’s not only a physical outcast, who lives on the edges of society (literally) with her two sons fathered by Jason, she’s also a spiritual outcast without everything that grounded her to nature (and, by extension, to herself). It would have been hard for audiences following every paparazzi photo Maria and Aristotle — and, subsequently, Jackie and Aristotle — to not map this metaphor onto the personal life of the movie’s star. While Jason and his society represent rational thought, so much pragmatism means that they’re also afraid of emotion and are too far-removed from empathy.

As she did in the Dallas production of Cherubini’s Medea in the wake of her dismissal from the Met, Maria once again threw herself into the role of Medea to the point of masochism. She insisted on watching every scene, even if she wasn’t in it, along with the rushes, even if they kept her up until just before she needed to wake up at 6am for her call time. It got to the point where the schedule, combined with Maria’s chronic low blood pressure and a particularly grueling scene that forced her to run back and forth in a dry riverbed under a scorching July sun, caused her to faint. When she came to, she apologized for holding up the production.

Maria and Pasolini both saw Medea as a victim of circumstances, albeit one who refuses to remain passive (even if it means burning it all down). One’s work complemented the other’s. Maria’s backstory makes her especially empathetic in Pasolini’s close-ups of Callas’s face, close-ups which she hated out of an abundance of self-loathing and he loved as classical sculptures.

Medea ends as abruptly as it begins, without the sort of grand finales that accompanied bel canto opera. In killing her children and herself, Medea has her revenge on Jason — as well as a means of returning to the natural world from which she has spent the last decade far removed. Across the flames engulfing her home, she shouts at Jason, “Nothing is possible anymore!” Before the overtone of Callas’s breath can fully dissipate, the film ends.

It’s an electrifying scene, and you can’t help but delight in Medea’s revenge, in part because it also feels like Maria’s. Here was a woman whose life was built on the struggle between her own inner nature and the outer world. The latter, so seemingly afraid of the former (especially in the Mad Men years of the 60s when women who weren’t subservient were still hysterical), enjoyed its own form of colonization: Keep the best of the art, leave the rest of the artist. What we would now consider post-traumatic stress disorder, linked to both childhood trauma and the ongoing blows of the entertainment industry, Callas’s own behavior was, in its time, presented as primal, uncivilized, and barbaric. Which meant that she had to be repressed.

While Medea garnered positive reviews (even for its inconsistencies, New York Times film critic Vincent Camby said he would “rather sit through the 10 worst minutes of it than the five best minutes of Michael Cacoyannis's reverential adaptation of The Trojan Women), it wasn’t a commercial success. Much of the praise, including for Callas’s own performance, also became quickly eclipsed by a more pressing question: Were she and Pasolini engaged?

On the film’s wrap, Pasolini had gifted Callas a ring studded with an antique Turkish coin. It seemed like the pair had also developed a genuine friendship, with Maria looking past his blasphemy and Marxism. Pasolini, meanwhile, felt their connection was so natural and deeply-rooted that it was as though they had known each other their whole lives.

For a press (especially an Italian press) still in the final days of the La Dolce Vita decade of star worship, there was no room for subtlety. One headline, featuring a photo of the pair sharing what seems now like a relatively chaste airport kiss, read: "Signor Pasolini, e' vero che sposera' la Callas?"

Today, there are still people who knew Callas and Pasolini who believe this was, for a time, the case. Others believe that Callas was either completely naive or in willful disregard of Pasolini’s sexual preferences and convinced herself that he wanted to marry her. A 2017 documentary (which seems to not exist online outside of its trailer), L’isola di Medea, explores this relationship in great depth from the people who witnessed it firsthand.

Nadia Stancioff, who worked as Maria’s assistant beginning on the set of Medea, says in this trailer, “She always wanted to take their relationship one step further, not knowing that he only wanted her friendship.” However, in her 1987 memoir, Maria: Callas Remembered, she was more conservative with her assumptions, suggesting then that Callas knew her relationship with Pasolini was only, albeit deeply, platonic, “but at times she purposely avoided facing the truth.”

But, even 43 years after her death, people continue to fuel the legend of Maria Callas as a woman who lived for love, and never truly found it.

“I often wonder, will I ever really be happy, or will I merely pass my life always struggling to survive,” Maria wondered in an interview with John Ardoin, echoing the claustrophobia of Medea in exile. “My hopes have been up to the skies and then — bang! — down. What does one do?”

Loneliness is a common Callas trope, even within her own lifetime. While Meneghini insisted time and again that their marriage was happy and he was well-loved, others who now talk of Callas remember her as profoundly unhappy. “There has been perhaps only one faithful companion to Maria throughout her life,” director Franco Zeffirelli claimed. “Her loneliness.”

But it also seems like that’s the opera plot that outside observers wanted Callas’s life to follow. After all, it heightened the value of the art itself to have these additional details, to have a greater sense of context.

Towards the end of her singing career, Callas began to receive fewer accolades. Terrence McNally, whose play Master Class was based on Maria’s life, recalled an entire performance of Medea at La Scala where she was hissed. In 1997, McNally wrote:

“To half the audience it seemed that Callas the soprano and Callas the woman received precisely the audience and critical drubbing they deserved.”

Her colleague, the baritone Tito Gobbi, once said, “I think Maria was not really a very happy person. She had some good moments in her life, but I never saw her really happy.” Running into her once in New York, Gobbi invited Maria out to dinner with his wife and young daughter. At the end of the night, walking his friend back to her hotel, she turned to him and said, “Listen, I am alone. I'm so lonely. I have not even my little dog to keep company. Why don’t you buy me another ice cream, and I’ll stay a little longer with you?”

But this loneliness is only one part of the story — and its roots are just as important to Maria Callas’s biography. What happened to her is as essential as what she subsequently did.

Memorializing her in Der Spiegel after her death, the German film director Werner Schroeter recalled a dinner with Callas where an American oil baron told him, “‘It must be wonderful to have your cock blown with La traviata on the voice cords.’” Schroeter’s first impulse was to strangle the man.

“It must have been very strange to live with the consciousness and awareness that the people to whom she had given the greatest of gifts responded with a kind of curious contempt,” Schroeter concluded.

The changing social mores beyond the world of classical music and opera are also important here. What Maria and Medea both lacked, and what Dani finds in Midsommar, is a collective empathy. In one of the movie’s other famous scenes, Dani, after catching her cheating boyfriend in the act, breaks down in sobs.

The cries echo her wails at the beginning of the film when her worst fears are confirmed and her sister has taken her own life, as well as the lives of her parents. In that scene, Christian (who was about to break up with Dani), holds her, speechless and dead-eyed. Here, among the Hårga, Dani is surrounded by a half-dozen other women who mirror her sadness. Not only do they mirror it, they seem to inhabit it with her. For the first time in the entire film, she’s emotionally validated. She’s allowed to feel exactly what she feels. Contrast this with the image of Maria Callas, still inside her Madama Butterfly kimono, understandably upset after being served papers as part of a lawsuit.

“How, then, can we fittingly remember Callas,” wondered journalist Marion Lignana Rosenberg, who devoted the latter part of her life to a project that aimed to re-vision the Maria mythos.

Perhaps in that spirit of re-visioning, we can see Maria Callas as Dani. Rather, we can see Dani as Maria. As what Maria deserved. At the end of Medea, Callas, while locked in a shouting match with Giuseppe Gentile’s Jason, cracks a rueful smile for a moment. It’s the seedling of happiness, of homecoming as she returns to the earth. It’s a smile that, 50 years later, fully blooms across Pugh’s face as Dani while the Hårga temple burns. She has arrived home.

The history has not yet found its conclusion, perhaps because there is no conclusion. But in recent years, it has also become a form of happiness in the growing number of people coming together to validate it. It has found a home.

Thanks for subscribing to Undone. Next week’s story will be less epic in word-count, but look at something as grand in scale: Classical music in East Berlin.

Further Reading

The following books are referenced in Parts 1 and 2 of “Maria, Medea, and Midsommar”:

My daughter Maria Callas by Evangelia Dimitriadou/Evangelina Callas (1960)

Maria Callas: The Woman behind the Legend by Arianna Huffington (1980)

My Wife, Maria Callas by Giovanni Battista Meneghini (1981)

Maria: Callas Remembered by Nadia Stancioff (1987)

Sisters by Jackie Callas (1989)

Interviews with Maria Callas are largely credited to the following documentaries:

Callas: In Her Own Words by John Ardoin

Maria by Callas by Tom Volf

The history of Pasolini’s Medea comes largely from Stancioff, as well as:

Pier Paolo Pasolini by Stephen Snyder (1980)

Pier-Paolo Pasolini: Cinema as Heresy by Naomi Greene (1990)

Pasolini Requiem by Barth David Schwartz (1992)

Vocal Apparitions by Michael Grover-Friedlander (2005)

You can watch Medea in full on YouTube. I highly recommend it.