Revisionist History: Bernstein at the Berlin Wall

When rock critic Jonathan Cott met with Leonard Bernstein in November, 1989, it was the last long interview the conductor and composer would give. It was a heady time for both Bernstein and the world, which Lenny would sum up in six words to Cott:

“The Berlin Wall is fucking down!”

Leonard Bernstein with assistant Craig Urquhart at the Berlin Wall, December 1989. Lenny had borrowed the hammer from the boy in the red jacket to get his own piece of the Wall. (Photo: Andreas Meyer-Schwickerath)

For Bernstein, it was one of the most exciting things that had happened in his 71 years, second perhaps only to the Kennedy inauguration. And, to his credit, Lenny had lived through a lot: Born in Lowell, Massachusetts in 1918, he was a little over two months old when Armistice Day ended World War I. He survived the HUAC era, during which he was labeled a “communist dupe” by Life magazine. He survived the turbulent process of writing and mounting Candide (whose helping hands ranged from Lillian Hellman to Dorothy Parker to Bernstein’s own wife, Felicia). He survived the long stretch of social and political disillusionment that was the 1960s, and the ire of Richard Nixon in the 70s (an ire that contributed to an 800-page FBI file on Lenny).

In 1976, after nearly 25 years of marriage, Lenny left Felicia to live with another man. When Felicia was diagnosed with lung cancer the following year, Lenny moved back into their home in East Hampton to take care of her. She died in the summer of 1978.

Despite the nature of their marriage, Bernstein was nevertheless devastated. Longtime friend Betty Comden wrote to Lenny on July 2 of that year: “I think of you and feel for you, and I think of Felicia, and what this last year must have been like for you, and the void that is now, and I wish I could write something to lessen the pain so visible in your eyes.… You must not blame yourself for not coming through this as a kind of patriarchal leader and rock of ages.” About six weeks later, André Previn would also comment on his friend’s depression, which became a theme of the following decade.

In retrospect, the ‘70s seemed, for Bernstein, like a last-ditch effort to affect political and social change through art; to make music more intensely, more beautifully, and more devotedly than ever before. 1971’s Mass earned scrutiny from Nixon’s advisors, who were convinced that the Latin texts were encoded with lyrics to embarrass the president. Haledmann described the premiere to the president, who called the affair “absolutely disgusting.” But, if Bernstein was proud to have been called a “son of a bitch” by Nixon, he was less enthused by the reception for his 1976 musical, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. It closed on Broadway after a week.

By the 80s, Lenny was exhausted: with politics, with life, perhaps even with himself. His next major theatrical work, the opera A Quiet Place, was a moment, in his daughter Jamie’s words, “of turning inward, to a ravaged psychological landscape.” It was a landscape that made writing more difficult, as Lenny tried to make up for his increasing age and decreasing physicality with a “prodigious [quantity] of uppers, downers, and alcohol [put] into a body that was growing ever less efficient at metabolizing all those substances.” On the podium, Lenny would have to run offstage between finishing a piece and taking his bows, in order to inhale from both an oxygen tank and a cigarette.

Lenny grew more manic as the decade wore on. Things seemed no less rosy with Reagan in the ‘80s as they had with Nixon in the previous decade. He began to spend more and more time in Vienna. “He would never again find the sense of optimism and progress that he had experienced in the last years of the 1930s and up to the late 1940s,” added Barry Seldes in Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician.

It could have been that Bernstein would spend his final years in exile and isolation. Yes, he was still earning applause for his performances of Mahler and Beethoven. But, when A Quiet Place premiered in 1983, it did not redeem his flops from the previous decade. “To call the result a pretentious failure is putting it kindly…as hollow and faddish as Mass,” wrote Donal Henahan for the New York Times. In Newsweek, Alan Rich called it a “dreary psychological quagmire.”

Bernstein for the New York Times, October 30, 1988

In October of 1988, Bernstein wrote an op-ed for the New York Times after returning from a two-month sojourn in Europe, declaring that he wanted to redefine “that newly naughty ‘L-word’ — liberal,” a word, he noted, derived from the Latin “liber,” meaning free:

“To tax the factory worker and the outright poor so that the rich can get richer is tyranny,” he wrote. “To call for war at the drop of a pipeline (while secretly dealing for hostages), to teach jingoistic slogans about armaments and Star Wars, to prescribe the weapons industry for the health of our doped-up credit card economy, to spend a dizzying percentage of the budget on arms at the expense of schools, hospitals, cultural pursuits, caring for the infirm, and homeless — these are all forms of tyranny.

“Who fought to free the slaves? Liberals. Who succeeded in abolishing the poll tax? Liberals. Who fought for women’s rights, civil rights, free public education? Liberals. Who stood guard and still stands guard against sweatshops, child labor, racism, bigotry? Lovers of freedom and enemies of tyranny: Liberals.”

And then, with a seeming suddenness that echoed the weekend in which it went up, the Berlin Wall came down in 1989. While there were thaws in the Cold War leading up to the night of November 9 of that year, the specifics of that evening — from a botched press conference to a snap judgment at one specific border crossing — were more accidental. Just over a year after he parsed out freedom and liberalism for the Times, Lenny was watching Berliners cross from East to West for the first time in nearly three decades.

As noted last week, Christa Ludwig, a soprano who had spent a great deal of her career working with Bernstein and a Berliner, was happy about this news as well. “But how disappointed I was that many young people were completely indifferent to the reunion. Of course, they had never experienced an undivided Berlin, and I thought it was horrible that almost two generations knew only a divided city.”

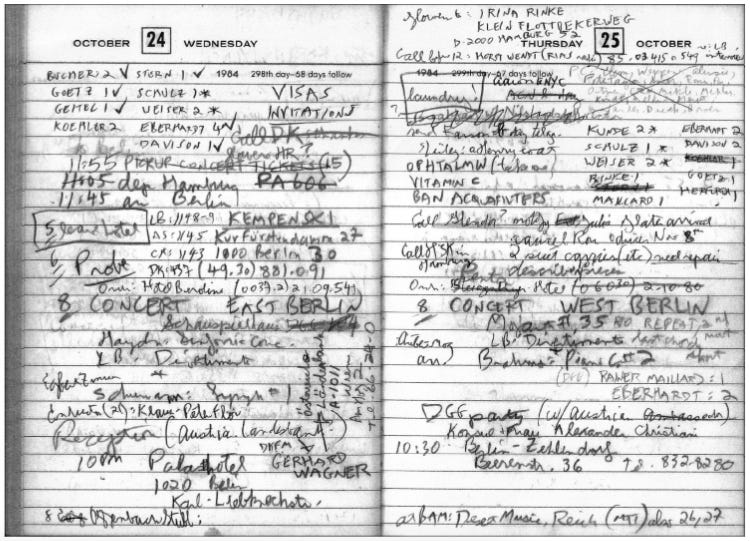

An earlier set of concerts for Lenny between West and East Berlin, documented in his assistant Charlie Harmon’s datebook (via On the Road and Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein)

While Jonathan Cott was fact-checking his piece on Lenny for Rolling Stone in December of 1989, Bernstein was preparing to return to Berlin. He would first be in London, to lead a concert performance of Candide with the London Symphony Orchestra, a work that is about nothing if not freedom. Christa Ludwig would be there to sing the Old Lady, alongside Jerry Hadley in the title role, and June Anderson as Cunegonde. Most of the cast, including Bernstein himself, would be hit with the worst flu epidemic in 14 years. Both Lenny and June Anderson would still be suffering its effects when they arrived in Berlin just after Candide for what would become one of Bernstein’s most monumental performances.

The concert itself hadn’t been Bernstein’s brainchild. The idea of a joint concert between East and West German orchestras came up in the days following November 9. On November 12, West Berlin’s Philharmonie opened up for free to East German citizens, who filled the seats and aisles for Daniel Barenboim leading the Berlin Philharmonic in Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1 and Symphony No. 7. Pianist and conductor Justus Frantz made the next step, as director of West Germany’s Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, in both inviting Bernstein to conduct and choosing the repertoire, explaining to the AP: “Europe is opening up. All men are becoming brothers, and so we chose the Ninth Symphony and musicians from all nations as a salute to freedom.”

In addition to the BRSO, the pickup orchestra included members of East Germany’s Dresden Staatskapelle and musicians from orchestras that represented the four countries that had initially partitioned Berlin in 1945: the New York Philharmonic, the London Symphony Orchestra, the Orchestre de Paris, and the Orchestra of the Kirov Theatre (known today as the Mariinsky). No small fraction of the musicians assembled onstage that week were citizens of a country — two countries, in fact — that would no longer exist by the middle of the next decade.

For his part, and continuing his commitment to redefining the naughty L-word, “liberal,” Bernstein made one small but significant change to the Schiller text that Beethoven set for the symphony’s final movement: Instead of an ode to joy (“Freude”), it was now an ode to freedom (“Freiheit”).

The Ninth was also significant beyond Schiller’s text. In the same year that Bernstein was expanding his FBI file with Mass, the Commission of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe enacted Resolution 492, which would lead to the adoption of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” as the European anthem in the following year, 1972.

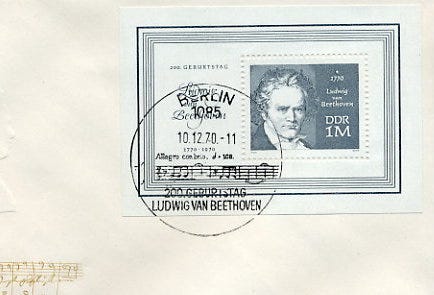

All of this came on the heels of Beethoven’s bicentennial celebrations in 1970, which was (like the reopening of opera houses and concert halls after the War) another sort of cultural arms race between West and East, each vying for ownership of the composer as their native son. Then, the GDR continued to position Beethoven as the revolutionary hero, not unlike Lenin (whose own centenary was also in 1970). A 1969 resolution passed by the Politburo declared in part that “Beethoven’s work accompanied the ascent of the workers to the [position of the] victorious class in the GDR.”

But East Germans were also looking to move past the trope of Beethoven as revolutionary. Musicologist Harry Goldschmidt, who presided over the GDR’s Beethoven year, argued that the celebrations “must serve as a starting point to open up the complete Beethoven for our musical life… [including] ensuring that [Beethoven] not is standardized according to a few works and reduced to the level of specific clichés.” (In some ways, this presages what pianist Sharon Su would write nearly 50 years later in the lead-up to Beethoven’s 250th celebrations: “Beethoven was a person. Music is made by people, not gods. We need to abolish the circular argument ‘great music is great because it is great’ if we want to have productive conversations about the role of people and art in our society.”

When the European Parliament moved to make “Ode to Joy” its official anthem, the GDR shot back with a statement:

“Beethoven’s music has become a byproduct of the capitalist leisure industry; it is disfigured or made the object of the most extreme modernist attempts on its life. At the same time, they strive to keep up appearances by presenting concerts and expositions abroad in order to mask a reality in violent contradiction with Beethoven’s humanism.”

On Christmas morning, over a thousand people crammed into what would soon be rechristened the Konzerthaus, with more crowding the square in front of the hall to watch the performance in an outdoor simulcast. It was one of two performances that Lenny would lead of the Ninth in Berlin: The second was performed in the West at the Philharmonie, timed to end just as West Berliners could enter the East without visas for the first time since the city was divided.

Musicologist Richard Taruskin (who, coincidentally, was born just a few weeks before VE Day), would give the event one of its few major, existing reviews in 1995 for the New York Times, calling it one of the few times he hated Beethoven’s music (or, more accurately, “what we’d made of it”). While it was a moment that cemented Leonard Bernstein’s image of musician-diplomat, to Taruskin it was a sloppy performance given by “hurriedly hand-picked” musicians. More to the point, he argued, East Germans had suffered no dearth of Beethoven during the GDR. In fact, they were the ones looking to go beyond specific cliché, beyond the byproduct of capitalist leisure.

The GDR’s Beethoven stamp to commemorate the composer’s 200th anniversary, 1970.

The West wasn’t entirely convinced by the gesture, either. A week before the concerts, Klaus Ubach took the event to task in Der Spiegel, calling it a unification “in philharmonic gluttony… with the sky-storming screams of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.” The problem wasn’t that Ubach missed the meaning in the pieces that came together. He saw the meanings, and that in and of itself was the problem. The calculations of bringing the concert together in the Christmas season, “at the San Andreas Fault” of Germany’s post-war identity (and in a city that wore its psychological quagmire on its sleeve, no less), a concert presented, in Ubach’s words, “urbi et Gorbi” (a play on the papal blessing “urbi et orbi,” to the city and the world).

“All people become brothers and sisters, listeners and spectators, here and there, with Lenny, Jussi, and Beethoven's Opus 125. Mwah,” he wrote, the disdain lodging in that final smack of a kiss.

Perhaps the greatest sin for Ubach, however, was the packaging: While the musicians performed free of charge, the German production company Unitel “took on the patriotic duty” of selling the broadcasting rights to the concert to over 20 countries. Deutsche Grammophon was quick to preserve it on CD. Was this concert a revolution, or retrenchment?

(“Is this not the moment to celebrate, not an individual birth, but a collective death?” Pierre Boulez wrote of Beethoven’s bicentennial in 1970. “Is it not a way of reassuring ourselves, now that we suspect that the supremacy to which we have grown accustomed is on the point of collapsing?”)

The inarguable truth about context is that it changes. Jonathan Cott’s profile of Leonard Bernstein for Rolling Stone was published in November 1990. Between his time with Lenny in 1989 and the interview going to print, the GDR no longer existed; East and West had officially merged on October 3 of that year. A few days later, on October 9, Lenny — whose health had never fully recovered from the issues plaguing him in Berlin that winter — announced his retirement from conducting. Less than a week later, he was at his home in The Dakota when he suffered a fatal heart attack.

Last November marked the 30th anniversary of the end of the Berlin Wall. Its 25th anniversary in 2014 was celebrated with a revisit of the “Ode to Freedom,” performed by Daniel Barenboim, who led the initial “welcome concert” in the West in 1989, with a group of soloists that seemed like a nod to the multinational cast of Bernstein’s Ninth (American soprano Renée Fleming, Latvian mezzo Elīna Garanča, formerly-West-German tenor Jonas Kaufmann, and erstwhile-East-German bass René Pape). Entering 2020, Beethoven’s Ninth gained added resonance with both the composer’s 250th anniversary and the year of Brexit.

But even in the first few months of this year, the context shifted. As unanticipated as the Wall and its fall before it, COVID-19 became the basis for a global pandemic that has forced social isolation, and to a lesser degree, revealed many of the weaknesses within arts institutions — many of which are pegged to the same opportunism that drives concept concerts and their requisite merchandising.

While pianist Igor Levit used the shutdown to stream over 50 solo concerts from his home, the Metropolitan Opera produced a starry gala with singers performing from their living rooms, closing with the company’s orchestra and chorus in “Va pensiero” from Verdi’s Nabucco. Unmentioned on the live stream was the fact that the salaried orchestra and chorus had not been paid in over a month.

What matters more in a performance: the art or the context? Is it even possible to take one definitive side of the argument? For audiences in West Berlin in 1961, Mozart’s Don Giovanni, which exists in an abundance of social and political context, was given as almost an antidote to the political realities that were hiding in plain sight just outside of the Deutsche Oper Berlin. Just over 28 years later, a performance of Beethoven that straddled both East and West Berlin made politics and context the main soloist.

Context then becomes a deeply personal (as well as sometimes political) question. One that could take a lifetime to answer, and by then the answer may have changed six times over. Here are some less complex, but no less personal, questions to ask in the moment:

What are we listening to?

How are we listening to it?

Above all: Why are we listening?

Thanks for subscribing to Undone. Next week: the Met gets sued.

Further Reading and Watching

On the Road and Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein: My Years with the Exasperating Genius by Charlie Harmon (2019)

Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein by Jamie Bernstein (2018)

Composing the Canon in the German Democratic Republic: Narratives of Nineteenth-Century Music by Elaine Kelly (2014)

The Leonard Bernstein Letters edited by Nigel Simeone (2013)

Dinner with Lenny: The Last Long Interview with Leonard Bernstein by Jonathan Cott (2012)

Beethoven in the Shadows of Berlin: Karajan’s European Anthem by Esteban Buch for Dissent (2009)

Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician by Barry Seldes (2009)

The Danger of Music and Other Anti-Utopian Essays by Richard Taruskin (2008)

Articles cited are linked in-line, but one piece that I read but didn’t reference here that is worth a dive is Tom Wolfe’s “Radical Chic” for New York Magazine, published in June, 1970. (There’s also an oral history of the piece.)

You can, of course, watch the full “Ode to Freedom” on YouTube.