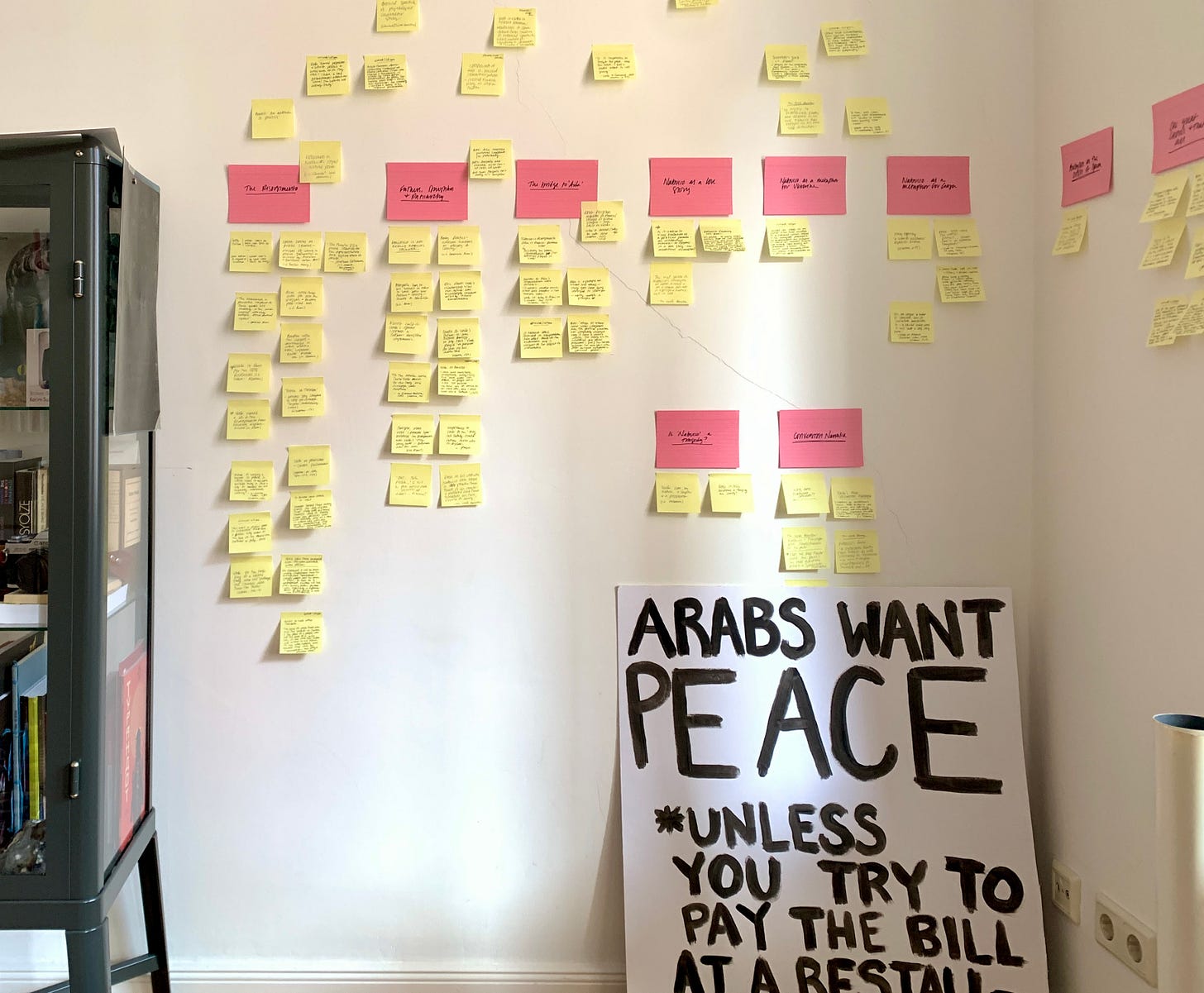

Over the last six months, I’ve been entrenched in Verdi’s Nabucco, examining the work from every possible angle: It’s an opera about liberation. It’s an opera about father-daughter relationships. It’s an opera about my own family (including members who reportedly performed in its premiere). It’s a bridge from Verdi’s early-career, Risorgimento-driven optimism to the latter-day ideological letdown of that same hope embedded in Aida. It’s one great chorus embedded in a bunch of cabalettas. It’s one extended mad scene, nevermind the chorus. It’s a conversion narrative. It’s a love story. It’s a love letter to Orientalism. It’s a break-up letter with the Habsburg Empire. It’s a metaphor for Italian unification. It’s a metaphor for the Holocaust. It’s a metaphor for Berlusconi’s Italy. It’s a metaphor for Ukrainian sovereignty. It’s a metaphor for Zionism (positive). It’s a metaphor for Zionism (negative).

I can credit my renewed fascination with the opera in a performance that I saw in Lviv in May. I was lucky to see a rehearsal of it as well, without the costumes and full sets. Watching the LNO chorus in their street clothes sing “Va pensiero,” a chorus about their country so beloved and lost, was a much clearer object lesson in history’s capacity to repeat itself. (Art is large, it contains verisimilitudes.) After the performance itself, I spoke with a 20-something couple in my row. It was their first opera together and I was eager to understand what they saw in a moment like “Va pensiero” from the vantage point of being in a country at war. I was surprised when the woman honed in more on the love story between Fenena and Ismaele, likening it to Romeo and Juliet.

Verdi himself seemed to be peripherally interested in it at best, but the woman’s viewpoint that Nabucco was, in fact, a story about how love triumphs over adversity was enough to send me down a Pepe Silvia-esque rabbit hole of reconsideration. I found more and more ways of looking at Nabucco, to the point that discovering a new vantage point also revealed five or six others in its wake. All of them seem to me both precious and prescient In These Times™.

Which is how I wound up in the Berlin Staatsoper last month for the company’s first production of the work in over 60 years. I hadn’t planned on it, but I wound up covering the performance in a recent blog post for the London Review of Books, because the most interesting aspects of the production — the ones that most brightly illuminated the basic DNA of one of Verdi’s most Risorgimento-coded operas — were accidental and tangential to the production itself. There was the involvement of conservative Prussophile Christian Thielemann, the Staatsoper’s new music director who, along with incoming artistic director Elisabeth Sobotka, is credited with programming this production as the opening salvo of his inaugural season.

There was the casting of Anna Netrebko, whose inherent Main Character Syndrome took over the character of Abigaille (no Zuul, only Anna). Her interpretation was best summed up by a caption she herself posted to Instagram: “Just let me be a Queen 👸🏼- because I worth it! And, yes… love me.. just LOVE me , papa.” At this point, it’s hard to see Netrebko in any performance and see the character. The significance of her casting was best summed up by a conversation I had with a Ukrainian opera director this summer: “Some people don’t see irony.”

There was also director Emma Dante’s abdication of any actual work around the context and relevance of Nabucco to a 2024 audience. Her insistence that “the current conflicts are much too complex to represent in an opera” seems to contradict the basic fact of Verdi’s early political works, but it also represents Germany’s baffling ability to back itself into materially aiding another genocide under the guise of “never again.” As I noted in the LRB, she underscores this at one point in the program book by describing the chorus of Hebrew slaves in Nabucco as “a people that is extraordinarily industrious.” (Just call me a slur next time, Emma.)

All of this served to feature, rather than flaw, the inherent politics of Verdi’s work. Art has an uncanny ability to reveal its political relevance even when its makers ignore — or actively try to bury — it. It’s an upending principle against posts like the one Netrebko made after her first Abigaille, sung in concert in Wiesbaden last year, which concluded that “Sounds of music are louder than protests. Always have been. Always will be.” Amid strict censorship in a pre-unified Italy, Verdi found a loophole in making the music the protest itself. It’s a similar loophole used by authors in the German Democratic Republic, smuggling contemporary political commentary to readers under the guise of ancient Greek myth.

In fairness to Netrebko, she wasn’t the only bit of casting that was accidentally illuminating in this production. I was especially happy to see bass Mika Kares in the role of Zaccaria (an eleventh-hour replacement for René Pape) after being moved by his Ivan Khovansky a few months ago in Helsinki.1 As Mussorgsky’s charismatic but ultimately tragic antihero, Kares filled the Musiikkitalo with the biggest of Big Dick Energy. Seeing that translate into Verdi’s Judean high priest brought an unexpected dimension to a character that’s usually played as a central but unexciting moral epicenter of the Babylonian melodrama. You could see how his Zaccaria was also playing the political cards dealt to him. Perhaps not to the malicious extent as the Babylonians but certainly in a way that was, if not cynical, at least more literate in the ways of the world.

I’m lucky that the LRB exists because I’m not sure there are too many other outlets that want to have me constantly smash art and politics together, making them kiss like Barbies. (It’s not lost on me, either, that of the three pieces I’ve written for their blog about this intersection, all stem from Verdi.) My read on art has always tended towards the ways of the world in which it was created; especially its historical and political contexts.

In eras like 2017 and the summer of 2020, when the social causes of the day are coming in fast and hot and social currency is in part predicated upon your hipness to these causes, this has made me welcome company. Over the last year, I’ve had more than one colleague ask me if I have to make everything about politics. I’m sure Thielemann — who once snapped that “I am not interested in what composers have eaten or what their political beliefs were; music doesn’t get better because one person was better than another person” — would choke me with one of his many striped polo shirts in response to this. It’s not that I believe art improves based on the moral or political alignment of its creators. But, much in the way psychoanalysts ask about your childhood, I like to know the environment that fosters an artist or her art. Even if it’s not the most important factor, it’s a fundamental one, and even art that tries to maintain neutrality or some degree of apoliticism is — as Dante’s Nabucco has shown — cannot existentially unmoor itself from the circumstances going on outside of the concert hall or opera house. Those institutions are just as dependent on the way the winds of politics blow.

This is a fact German institutions are being reminded of at this very moment amid a proposed 2025 federal budget that will cut independent cultural funding by roughly 50%. (Set to receive more money: the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation.) The Bundestag is also about to vote on a nationwide resolution that resurrects a proposal originally shot down at the state level in Berlin earlier this year: a bill against antisemitism, using the controversial IHRA definition of the word, that would have implications for the arts and academia — two sectors routinely portrayed as the Sodom and Gomorrah of “imported antisemitism.”2 For more on the specifics of this case, I recommend Ana Teixeira Pinto’s essay for Metropolis. What stands out to me most from her piece is the kicker: “This is not about the public putting pressure on power but power putting pressure on the public. This is state-sanctioned censorship.”

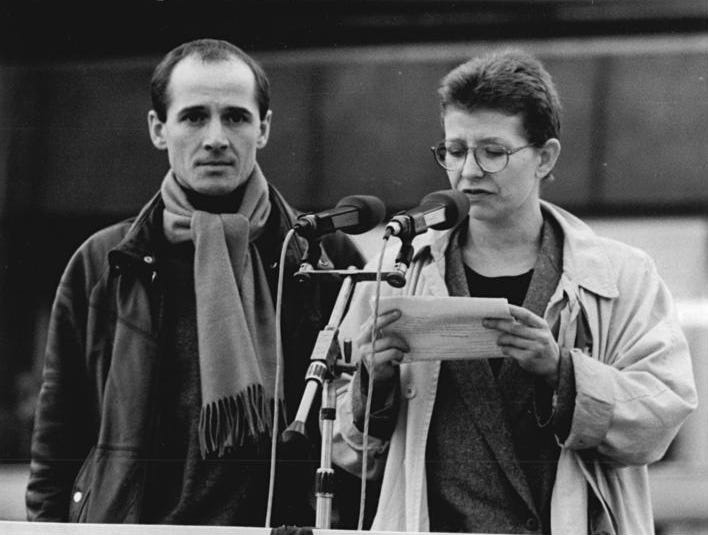

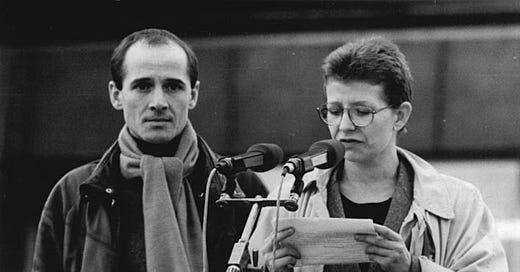

It’s an especially stark image to revisit this week as Germany prepares to celebrate 35 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall. I was recently talking with a friend about the 2006 film The Lives of Others, and its star, the late Ulrich Mühe. In the waning years of the GDR, Mühe joined the ensemble of the Deutsches Theater in East Berlin. He heard the protest embedded in the music. “For us actors it was an island,” he said of the theater. “We could dare to criticize.” On November 4, 1989 — 35 years and one day ago — he spoke at a demonstration on Berlin’s Alexanderplatz, calling for democratic reforms that protected the GDR’s constitutional rights to freedom of expression and assembly. “We also propose a constitutional amendment,” Mühe stated to thousands of compatriots. “Article 1, Chapter 1: We believe that a party’s claim to leadership must not be prescribed by law. Every claim to leadership must be earned.” This last line gets him the most applause (you can watch the full speech here).

Less than a week after that speech, the Berlin Wall (by accident as much as anything else) had opened. Mühe reportedly learned soon after that his wife at the time, actress Jenny Gröllmann, had spent the better part of a decade as an “Inoffizieller Mitarbeiter” (unofficial collaborator, or IM) with the Stasi. While Gröllmann denied that she had willingly or consciously taken on a role as an IM, the details of Mühe’s life through his wife’s lens were irrevocably part of his Stasi file. They divorced in 1990. Sixteen years later, Mühe had his international breakthrough role as the tormented Stasi official Gerd Wiesler in The Lives of Others. Asked how he prepared for the part, he said: “I remembered.”

I think these are the moments where, like my Lviv experiences with Nabucco, a work of art cracks open, its meanings malleable to any number of circumstances and contexts. On an election day that I’m meeting on the other side of a bout of covid that crept up on me just a few hours after I reluctantly mailed in my absentee ballot last week (an augur if ever there was one), I’m not sure exactly what use that has. But I know it has one.

PS: If you ever wanted to know what it would sound like if you replaced Netrebko’s vocals in “Anch’io dischiuso un giorno” with Ukrainian air-raid sirens, I’ve got you covered:

In another Mussorgskian connection, Fenena in this production was sung by Marina Prudenskaya, who I saw last season as Marfa in the Staatsoper’s own production of Khovanshchina. There, director Claus Guth refocused Marfa’s role as not only an Old Believer, but also a figure with ties to the noble class, who moves seamlessly between the three main factions at the heart of the opera. It’s analogous, in some ways, to how Fenena moves between the two warring worlds in Nabucco.

To debunk this dog whistle: Even with a dramatic increase in anti-semitic incidents reported last year compared to 2022 and a categorization of pro-Palestinian activism as antisemitic, the federal agency responsible for reporting on antisemitic incidents in Germany still reported that, in 2023, it was three times more likely that an antisemitic incident would be motivated by right-wing populism than Islamism — in 2022, it was 19 times more likely.

This was a marvelously written, finely woven consideration of poliltical resonance within a work, within the society which presents that work and within the composer of that work--and much more which can't be encapsulated in a comment. Many thanks.

loved this